In an old Italian crypt from the 17th century, two mummified brains have been found containing traces of cocaine. This is almost two entire centuries before the coca plant's psychoactive compounds were isolated to produce pure cocaine – one of the most addictive substances known to humans.

The burial chamber where the mummified remains were interred once used to serve a 17th-century hospital in Milan, but the site has been sealed up tight until very recently, so the drug traces found there were unlikely to be environmental contaminants.

Indeed, University of Milan forensic toxicologist Gaia Giordano and her team detected no traces of cocaine or its associated molecules in the surrounding environment.

The human remains were collected by archaeologists wearing protective equipment under the supervision of toxicologists, and stored in sealed, sterilized jars.

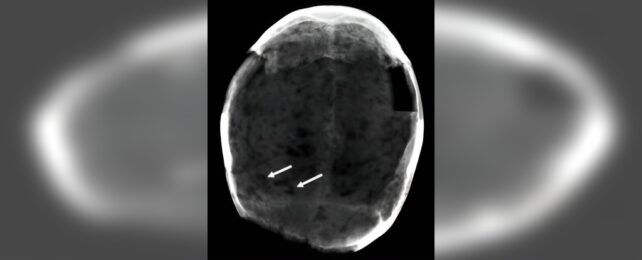

The cocaine molecules were found in the brain tissue of a male of 30 to 45 years of age, who had signs of tertiary syphilis on his cranium, and also in a brain that was no longer attached to its skeleton, meaning it could not be further identified.

Still, the presence of cocaine in these brains doesn't mean the mysterious patients actually consumed the plant. They could have just encountered it in the environment while living. So the researchers searched for signs of the chemicals that cocaine is converted to once consumed.

Giordano and colleagues detected benzoylecgonine in the brain samples, indicating that cocaine had indeed passed through the bodies of the two people before they died. The presence of hygrine, an alkaloid found only in the leaves Erythroxylum, the coca plant, further confirmed the drug was consumed in its plant form.

"The molecules detected in these human remains derived from the chewing of coca leaves or from leaves brewed as a tea, consistent with the historical period," the team concludes.

In its tea form, coca is a mild stimulant comparable to a strong cup of coffee.

The two former hospital patients were buried in a manner indicating they were not very well off socioeconomically speaking, suggesting coca leaves were cheap and easy to come by in 1600s Milan.

Evidence of ancient coca use has only been found with high confidence in biological remains from South America, where the plant is native and known to have been frequently consumed by the Inca population. None has ever been detected in human remains of European origin before now.

The recent discovery suggests coca was being traded between South America and Europe long before we knew it.

"The effects of the plant, including reduced hunger and thirst, as well as a sense of well-being, were known and controlled by the Spaniards and subsequently diffused to the rest of Europe," the researchers write, explaining Milan was ruled by the Spanish at the time.

Giordano and colleagues can't rule out that the patients had been prescribed the coca leaves as medicine at the hospital, but there are no records of the medicinal use of this plant in Europe during the 1600s, and the plant isn't listed in the hospital's pharmacological records.

It's therefore possible that struggling citizens of 17th century Milan might have turned to recreational drugs to make their world a bit more bearable, just like people still do today.

This research was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.