New research reveals that mushrooms and other fungi can keep themselves cooler than their surroundings. The discovery could tell us more about these organisms' evolution and how they might respond to continued global warming.

Like some of the best scientific discoveries, this temperature regulation was discovered accidentally, as one of the researchers was testing out a thermal camera during the pandemic – and noticed that mushrooms growing in nearby woods came up as cooler than the surrounding vegetation.

The researcher then recruited a team of molecular biologists from Johns Hopkins University in Maryland and a colleague from the University of Puerto Rico to take a closer look at what was happening.

"In contrast to animals and plants, the temperature and thermoregulation of fungi are relatively unknown," write the researchers in their published paper. "Our data suggest that not only mushrooms, but yeast and mold communities can maintain colder temperatures than their surroundings."

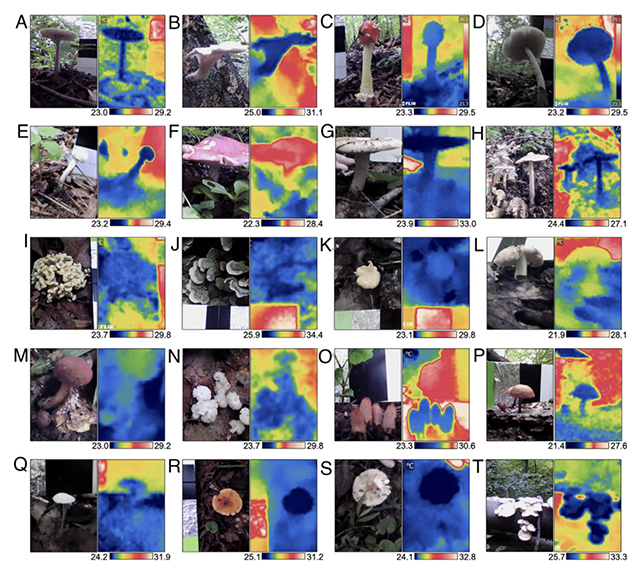

While mushroom cooling has been reported and observed, it hasn't been studied that closely. Here, the team analyzed mushrooms in the wild and other fungal species in the lab to check on temperature differences.

On average, mushrooms were shown to be 2.9 °C (5.2 °F) colder than the surrounding air, with a range of uncertainty of 1.4 °C (2.5 °F). With some mushroom species, the temperature of the mushroom was as much as 5.9 °C (10.6 °F) cooler.

Through lab experiments where water content and temperature could be manipulated, the researchers confirmed that mushrooms regulate their temperature through evapotranspiration, or releasing water into the air. Substantial amounts of water can be held under the mushroom caps before being released slowly and evenly.

Furthermore, other fungus types can perform the same trick, with colonies tending to be colder nearer the center. This seems to happen no matter the external temperature, even if it's close to freezing.

"We show that yeast and mold colonies are also colder than their surroundings and use the process of evapotranspiration to give off heat," write the researchers. "Relative coldness appears to be a general characteristic observed across the fungal kingdom."

As fungi compose around 2 percent of Earth's biomass, their cooling properties may help regulate local environments. The researchers tested this by fashioning a basic mushroom-powered cooler as part of their study. They used Agaricus bisporus to effectively reduce the temperature inside a sealed enclosure – more evidence of the cooling capacity of mushrooms.

This thermoregulation is important not just for understanding more about fungi but also in modeling climate change. These organisms play a vital role in the ecological cycles on Earth, and we need to know how they will adapt in the future and how they might help other plants and animals adapt too.

What the team didn't get into here is exactly why fungi like to keep cool. Previous research suggests that vapor water loss allows mushrooms to create local airflow to help disperse their spores, but many questions remain.

"The extent to which fungal temperatures vary with their environmental niche likely involves multiple factors that require further study," write the researchers.

"The temperature of wild mushrooms, as well as yeast and mold colonies, relative to their surroundings varies with the genus, suggesting that there may be species-specific differences in their capacities to dissipate heat."

The research has been published in PNAS.