Beneath the cold, dark waves of the Baltic Sea, a hidden piece of history lurks.

In Germany's Bay of Mecklenburg, 21 meters (69 feet) down, scientists have found an ancient stone megastructure, dating back to the Stone Age, more than 10,000 years ago.

Spanning a length of nearly a kilometer (0.62 miles) and consisting of large stones, the structure defies natural explanation – meaning it seems to have been deliberately constructed for some purpose, thousands of years before it was swallowed up by the sea.

The German research team led by geophysicist Jacob Geersen of Kiel University believes the structure to be a wall, perhaps to aid hunting efforts by the hunter-gatherer people who inhabited the region all those years ago.

They have named their discovery the Blinkerwall.

"The site represents one of the oldest documented man-made hunting structures on Earth, and ranges among the largest known Stone Age structures in Europe," the researchers write in their paper.

"It will become important for understanding subsistence strategies, mobility patterns, and inspire discussions concerning the territorial development in the Western Baltic Sea region."

Earth's land masses have changed significantly over the millennia, shaped by tectonic movement, erosion, and climate processes such as glaciation and sea level changes. Many coastal settlements and structures have been taken by the waves over time, languishing, both hidden from view and out of easy reach.

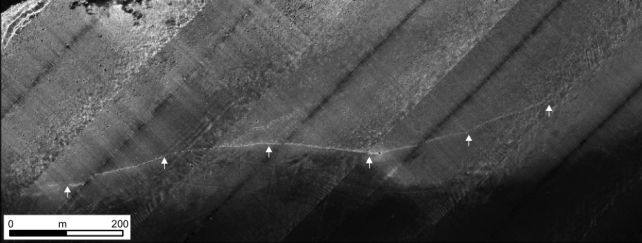

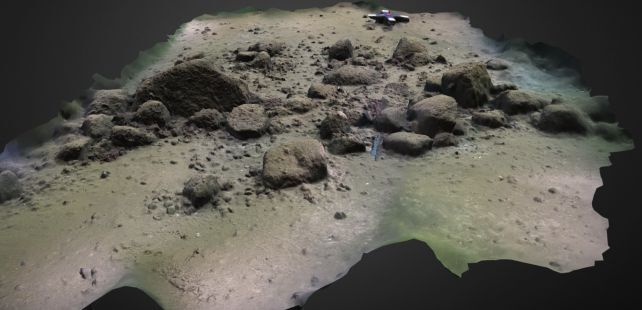

In recent years, though, continually developing technologies have started to reveal the hidden treasures on the seafloor. Geersen and his team found the Blinkerwall using high-resolution hydroacoustic imaging, an autonomous underwater vehicle, and human divers to explore the bay, and map the true extent of the structure.

The data collected revealed a long stretch of some 1,670 individual stones, spanning some 971 meters (3,186 feet). These stones tended to be less than a meter (3.3 feet) high and less than 2 meters wide, sitting side-by-side over the length of the structure.

The consistency and neatness, the team says, are unlikely to be the result of natural processes, such as glacial transport or being pushed by ice.

In addition, the structure appears to have been adjacent to an ancient shoreline or bog. However, the Blinkerwall was unlikely to have served as a fish weir, since the researchers could find no water flow as required for proper functionality.

Nor would it have served as a coastal defense, since 2 meters is too narrow for the base of a coastal wall. And the construction of a harbor, they say, is also unlikely, since the people who inhabited the region over 10,000 years ago were unlikely to be doing much sea-faring.

"Based on the information at hand," the researchers write, "the most plausible functional interpretation for the Blinkerwall is that it was constructed and used as a hunting architecture for driving herds of large ungulates." Those would have consisted, at the time, primarily of reindeer or bison.

It's not that strange an idea. Hundreds of colossal stone structures have been found scattered from the desert lava fields of Saudi Arabia to central Asia; scientists believe that these structures were also used to drive herds of animals, making them easier to hunt.

Although dating such structures is challenging, the researchers believe that the Blinkerwall was built more than 10,000 years ago, based on the age of surrounding features, and submerged beneath the Baltic Sea around 8,500 years ago.

Since then, it has remained sequestered beneath the waves, in a relatively pristine condition that makes it a valuable resource for understanding human history.

"The suggested date and functional interpretation of the Blinkerwall makes the feature a thrilling discovery, not only because of its age but also because of the potential for understanding subsistence patterns of the early hunter-gatherer communities," the researchers write.

"The discovery of this kind of structure shed light on many aspects of the regional hunter-gatherers, especially regarding their socioeconomic complexity."

The research has been published in PNAS.