Slowly but surely, the ground is regurgitating its secrets. The history that lies buried beneath the swirling sands of time yields, piece by piece, to technology.

But one such piece, in a well-explored region, has archaeologists a little baffled.

Near the famous ancient Great Pyramid of Giza, Egypt, ground-penetrating radar and electrical resistivity tomography have revealed a large, two-part structure, buried and concealed under a burial ground that has sat (more or less) undisturbed for more than 4,000 years.

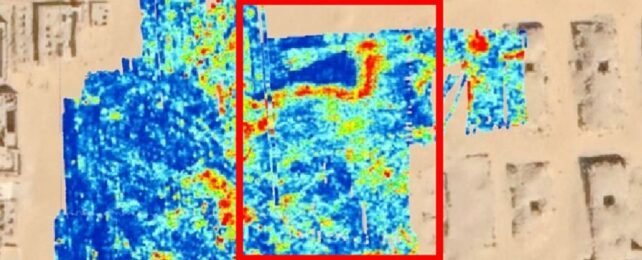

Under the Western Cemetery, west of the Great Pyramid, these scans revealed a shallow-L-shaped structure, spanning an area 10 meters (33 feet) by 15 meters, between 0.5 and 2 meters below the surface of the desert.

Below that appears to be a much larger structure, between 3.5 and 10 meters deep, covering an area 10 meters by 10 meters.

It's unclear what these structures might be, but their presence could yield new information about the Giza pyramid complex, and the long-dead humans who built it.

Technologies that can see what's below the surface of the ground without digging into it have given us a lot of discoveries in recent years, not just on Earth, but on Mars, and the Moon. They're an excellent way to gauge the history of a place without destroying any of the delicate evidence.

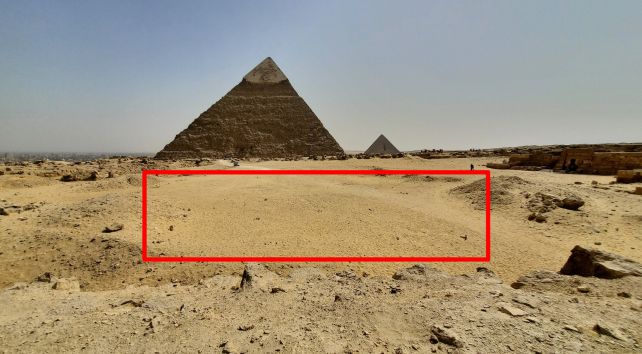

One part of the Western Cemetery has always been a bit of a puzzle. Where most of the ground is filled with graves and tombs, one rectangular piece was left bare and flat.

Led by archaeologist Motoyuki Sato of Tohoku University in Japan, a Japanese and Egyptian team set about studying this relatively unexamined parcel of land.

Ground-penetrating radar works by directing radio waves into the ground, and measuring them when they are bounced back. Materials with different densities and compositions below the ground reflect the radio waves in different ways, which means the technology can be used to map structures and geological formations underground.

Electrical resistivity tomography works in a similar way by detecting changes in the electrical resistivity of different subsurface materials.

Using these two techniques, the researchers found regions of varying density beneath the bare, flat section of the cemetery – and the density formed shapes that are highly unlikely to be natural, the team says.

This suggests that they were human-made, although their purpose remains a mystery. The shallower structure, the scans reveal, was filled with homogeneous sand, suggesting that it was deliberately filled in after construction.

The deeper structure, revealed by the electrical resistivity tomography, was a little more difficult to figure out.

It seemed to be filled with something highly resistive, which could be sand, but could also be a void, indicating some sort of hollow chamber. Because it can't be identified one way or another, the researchers refer to it as an "anomaly".

The alignment of both structures, they believe, is significant, and they suggest that the shallower one may have been an entrance to the larger one. Given the location of the structure, though, there is one explanation that seems highly plausible.

"We conclude from these results that the structure causing the anomalies could be vertical walls of limestone or shafts leading to a tomb structure," the researchers write in their paper. "However, a more detailed survey would be required in order to confirm this possibility."

The team's findings have been published in Archaeological Prospection.