New satellite data from the European Space Agency (ESA) reveal that the mysterious anomaly weakening Earth's magnetic field continues to evolve, with the most recent observations showing we could soon be dealing with more than one of these strange phenomena.

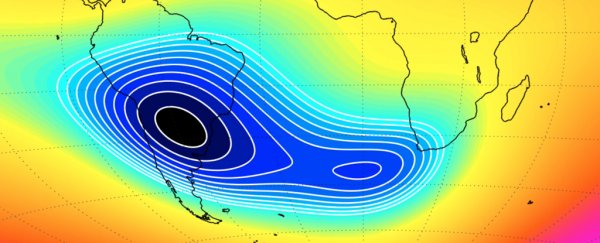

The South Atlantic Anomaly is a vast expanse of reduced magnetic intensity in Earth's magnetic field, extending all the way from South America to southwest Africa.

Since our planet's magnetic field acts as a kind of shield – protecting Earth from solar winds and cosmic radiation, in addition to determining the location of the magnetic poles – any reduction in its strength is an important event we need to monitor closely, as these changes could ultimately have significant implications for our planet.

At present, there's nothing to be alarmed about. The ESA notes that the most significant effects right now are largely limited to technical malfunctions on board satellites and spacecraft, which can be exposed to a greater amount of charged particles in low-Earth orbit as they pass through the South Atlantic Anomaly in the skies above South America and the South Atlantic Ocean.

In an area stretching from Africa to South America, Earth’s magnetic field is gradually weakening. Scientists are using data from @esa_swarm to improve our understanding of this area known as the ‘South Atlantic Anomaly’ 👉 https://t.co/ZqTBA9DmX4 pic.twitter.com/klc5SS7zYo

— European Space Agency (@esa) May 20, 2020

Not that the magnitude of the anomaly should be diminished, though. In the last two centuries, Earth's magnetic field has lost about 9 percent of its strength on average, the ESA says, assisted by a drop in minimum field strength in the South Atlantic Anomaly from approximately 24,000 nanoteslas to 22,000 nanoteslas over the past 50 years.

Exactly why this is happening remains a mystery. Earth's magnetic field is generated by electrical currents produced by a swirling mass of liquid iron within the outer core of our planet, but while this phenomenon appears stable at any given moment, over vast timescales, it's never really still.

Research has shown that Earth's magnetic field is constantly in a state of flux, and every few hundred thousand years (give or take), Earth's magnetic field flips, with the north and south magnetic poles swapping places.

That process could actually occur more frequently than people think, but while scientists continually debate when we might next witness such an event, even the regular, wandering movements of Earth's magnetic poles keep geophysicists guessing.

In any case, it's not fully clear how those reversals might be tied to what's currently going on with the South Atlantic Anomaly – which some have suggested could be caused by a vast reservoir of dense rock underneath Africa called the African Large Low Shear Velocity Province.

What is certain, though, is that the South Atlantic Anomaly is not sitting still. Since 1970, the anomaly has been growing in size, as well as moving westward at a pace of approximately 20 kilometres (12 miles) per year. But that's not all.

(Division of Geomagnetism, DTU Space)

(Division of Geomagnetism, DTU Space)

Above: Satellite data revealing the new, eastern centre of minimum intensity emerging beside Africa.

New readings provided by the ESA's Swarm satellites show that within the past five years, a second centre of minimum intensity has begun to open up within the anomaly.

This suggests the whole thing could even be in the process of splitting up into two separate cells – with the original centred above the middle of South America, and the new, emerging cell appearing to the east, hovering off the coast of southwest Africa.

"The new, eastern minimum of the South Atlantic Anomaly has appeared over the last decade and in recent years is developing vigorously," says geophysicist Jürgen Matzka from the German Research Centre for Geosciences.

"The challenge now is to understand the processes in Earth's core driving these changes."

Just how the anomaly will develop from here is unknown, but previous research has suggested disruptions in the magnetic field like this one might be recurrent events that take place every few hundred years.

Whether that's what we're witnessing now isn't fully clear – or how a split anomaly might end up playing out – but scientists are watching closely, as are we.