Galaxies come in many different shapes and sizes, but the basic ingredients seem fairly consistent. There's usually a big black hole at the center, a bunch of stars and gas, and a generous serving of dark matter that helps glue the whole thing together.

While dark matter is, well, dark, the stars, gas, and swirling core of heated material stand out with the radiant beauty of a city in the night.

However, one newly discovered dwarf galaxy located a mere 94 million light-years away is defying expectations. It's named FAST J0139+4328, and it's not emitting any optical light. In fact, it's barely emitting any light at all.

FAST J0139+4328 appears to be what is known as a dark galaxy. Aside from a small smattering of stars, the galaxy seems to be made up almost entirely of dark matter. A paper describing the discovery has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, and is available on preprint server arXiv.

"These findings provide observational evidence that FAST J0139+4328 is an isolated dark dwarf galaxy," write a team of astronomers led by Jin-Long Xu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. "This is the first time that an isolated dark galaxy has been detected in the nearby Universe."

Dark matter is currently the leading explanation for a weird discrepancy between the amount of normal, or baryonic, matter observed in corners of the Universe and the strength of the gravity required to hold it together. Put simply, there's just not enough baryonic matter to account for all the gravity. Galaxies are spinning so fast that they should fly apart without something else binding it all together.

Whatever is responsible for this extra gravity remains elusive. It doesn't seem to interact with normal matter in any way other than through gravity; nor does it emit any form of radiation we can currently detect. We simply can't see the source of this extra mass. Still, reserving a space for some kind of unknown material goes a long way towards resolving the problems we observe.

However, dark matter theory isn't perfect either. One problems is a discrepancy between simulations of the dark matter distribution in the Universe and the number of dwarf galaxies we see out there orbiting larger galaxies. There are way fewer dwarf galaxies than the simulations suggest there ought to be. This is known as the dwarf galaxy problem.

It is possible we're simply unable to detect some kinds of dwarf galaxy, such as those with very few stars, consisting primarily of gas and dark matter. Finding enough of them would help resolve the whole shortfall in dwarf galaxies.

Some candidate dark galaxies have been identified, but they are very close to other structures, which makes them hard to distinguish from blobs of debris ripped free by stronger gravitational forces.

An ideal dark galaxy candidate would be drifting by itself, isolated in space, where its identity could not be mistaken.

To search for such a galaxy, Xu and his colleagues used the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope (FAST) in China. They used the telescope during gaps in its observation schedule as a "filler" project to conduct a search for the radio emission of large clouds of neutral atomic hydrogen (HI) gas in intergalactic space, looking for features consistent with a galaxy.

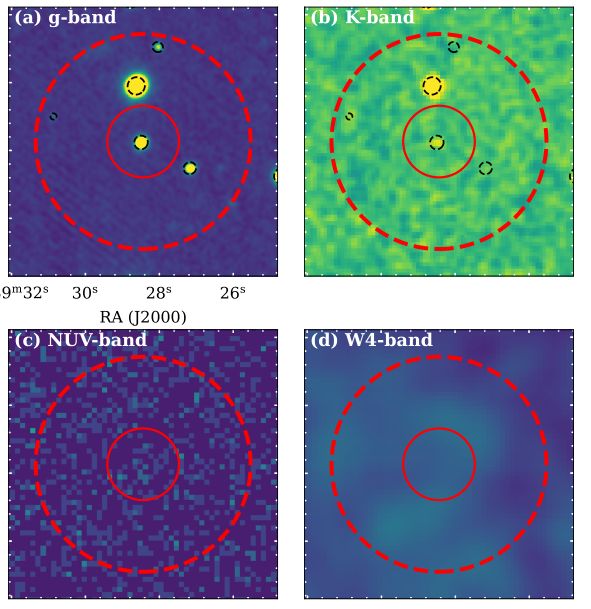

And they got a hit: the radio waves emitted by a cloud of HI 94 million light-years away were consistent with a rotating disk galaxy, without the optical light expected of one. Follow-up observations in infrared and ultraviolet revealed a faint smattering of stars.

All together, the data allowed the researchers to determine the properties of the galaxy, which they named FAST J0139+4328.

According to the team's calculations, the galaxy has an upper limit of 690,000 solar masses' worth of stars – and it contains 83 million solar masses' worth of HI. The total baryonic mass of the galaxy clocks in at around 110 million solar masses.

This, however, is just a drop in the bucket of the galaxy's total mass. The team was able to calculate FAST J0139+4328's rotation speed, and from that its total mass, which came in at 5.1 billion solar masses. That would mean that the galaxy is made up of around 98 percent dark matter.

It's expected that other scientists will attempt to confirm the nature of the object. In which case, it may turn out to be something different, as so happened with a galaxy called Dragonfly 44. In 2016 the galaxy was found to consist of 99.99 percent dark matter. Four years later, however, astronomers determined that Dragonfly 44 wasn't so abnormal.

But if it is validated as a dark galaxy, FAST J0139+4328 will have some very interesting things to tell us about the Universe around us.

"This is the first time that a gas-rich isolated dark galaxy has been detected in the nearby Universe," the researchers write.

"In addition, a galaxy is assumed to form from gas, which cools and turns into stars at the center of a halo. FAST J0139+4328 has a rotating disk of gas and is dominated by dark matter, but is starless, implying that this dark galaxy may be in the earliest stage of the galaxy formation."

The research has been accepted into The Astrophysical Journal Letters, and is available on arXiv.