Chugging quietly away in the dark depths of Earth's ocean floors, a spontaneous chemical reaction is unobtrusively creating molecular oxygen (O2), all without the involvement of life.

This unexpected discovery upends the long-standing consensus that it takes photosynthesizing organisms to produce the oxygen we need to breathe.

Biogeochemist Andrew Sweetman from the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) and colleagues made the surprising find while measuring seafloor oxygen levels to assess the impacts of deep-sea mining.

"The discovery of oxygen production by a non-photosynthetic process requires us to rethink how the evolution of complex life on the planet might have originated," says SAMS marine scientist Nicholas Owens, who wasn't involved in the research.

"In my opinion, this is one of the most exciting findings in ocean science in recent times."

In the midst of the Pacific Ocean, black, rounded rocks pepper the floor. Here, at depths of more than 4,000 meters (13,000 feet), oxygen levels slowly but surely keep increasing, the scientists' measurements showed.

"When we first got this data, we thought the sensors were faulty, because every study ever done in the deep sea has only seen oxygen being consumed rather than produced. We would come home and recalibrate the sensors but over the course of 10 years, these strange oxygen readings kept showing up," explains Sweetman.

"We decided to take a back-up method that worked differently to the optode sensors we were using, and when both methods came back with the same result we knew we were onto something ground-breaking and unthought-of."

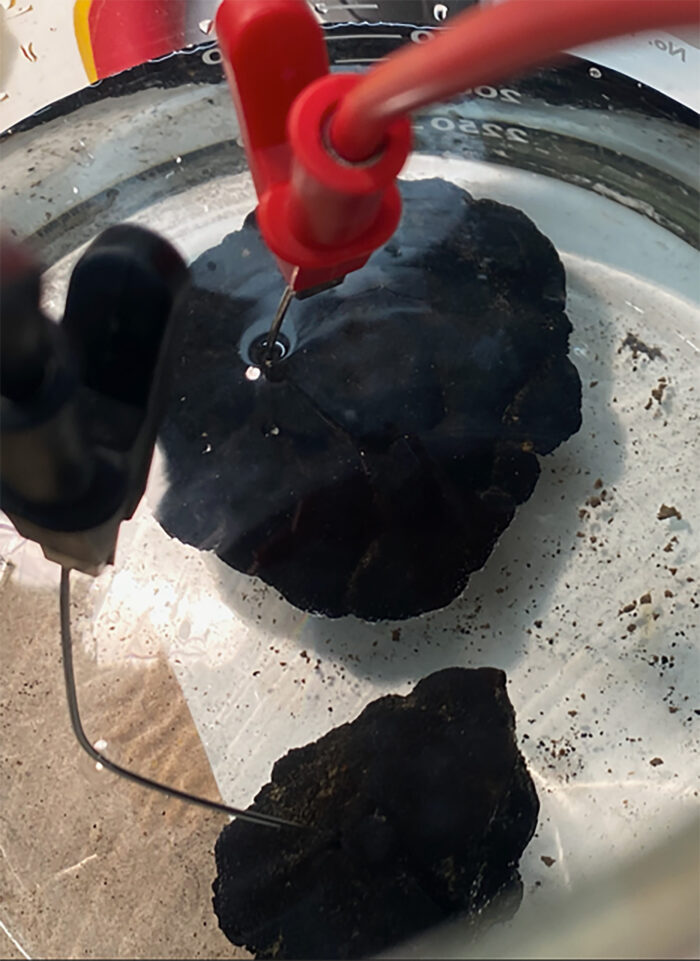

To investigate the mystery, the researchers collected some of the nodule rocks, to see if they were the source of this 'dark oxygen' production in the lab.

Scatterings of these nodules carpet vast areas of the ocean's bottom. They're natural deposits of rare-earth metals like cobalt, manganese, and nickel, all jumbled up in a polymetallic mix.

We value these exact metals for their use in batteries, and it turns out that's exactly how the rocks may be spontaneously acting on the ocean floor.

The researchers found single polymetallic nodules produced voltages of up to 0.95 V. So when clustered together, like batteries in a series, they can easily reach the 1.5 V required to split oxygen from water in an electrolysis reaction.

"It appears that we discovered a natural 'geobattery,'" says Northwestern University chemist Franz Geiger. "These geobatteries are the basis for a possible explanation of the ocean's dark oxygen production."

While there's still much to investigate, such as the scale of oxygen production by the polymetallic nodules, this discovery offers a possible explanation for the mysterious stubborn persistence of ocean 'dead zones' decades after deep sea mining has ceased.

"In 2016 and 2017, marine biologists visited sites that were mined in the 1980s and found not even bacteria had recovered in mined areas. In unmined regions, however, marine life flourished," explains Geiger.

"Why such 'dead zones' persist for decades is still unknown. However, this puts a major asterisk onto strategies for sea-floor mining as ocean-floor faunal diversity in nodule-rich areas is higher than in the most diverse tropical rainforests."

As well as these massive implications for deep-sea mining, 'dark oxygen' also sparks a cascade of new questions around the origins of oxygen-breathing life on Earth.

Ancient microbial cyanobacteria have long been credited for first supplying the oxygen required for the evolution of complex life billions of years ago, as a waste product of photosynthesis turning sunlight into their energy source.

"We now know that there is oxygen produced in the deep sea, where there is no light," says Sweetman.

"I think we, therefore, need to revisit questions like: Where could aerobic life have begun?"

This research was published in Nature Geoscience.