Thousands of light-years from Earth, the dramatic death throes of a giant star are playing out.

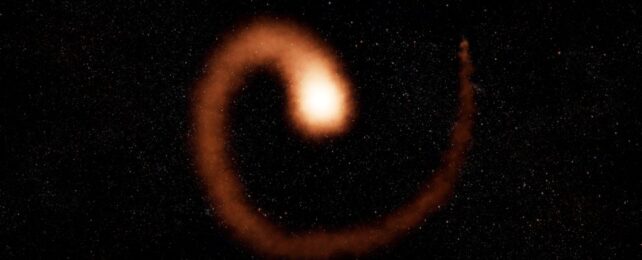

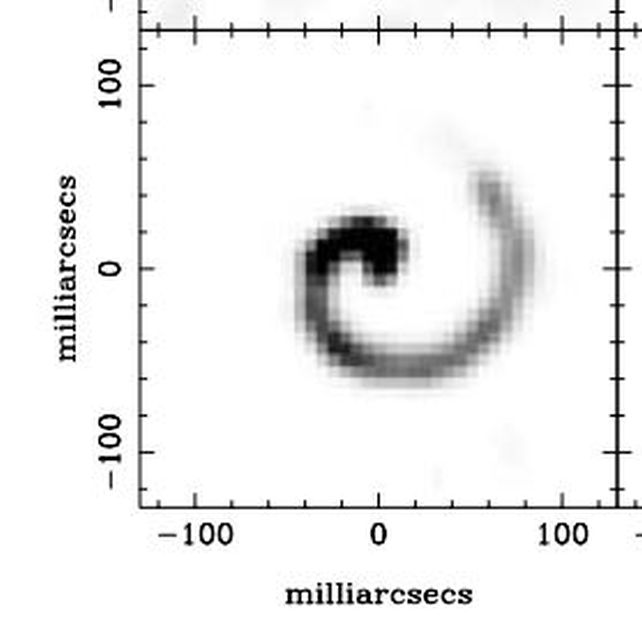

It's part of a star system called Wolf-Rayet 104 (WR 104), also known famously as the Pinwheel Nebula. Astronomers have confirmed the shape of the nebula is an interaction with a stellar twin – a binary companion in orbit with the dying star, which helps carve ejected material into a stunning spiral in space.

The discovery, and the newly identified position of the binary companion, mean we no longer have to fret about the Pinwheel star's imminent supernova.

We now know it's oriented in such a way that its gamma-ray burst would not lash Earth with a blast of deadly radiation – a possibility that led some to nickname WR 104's star the 'death star'.

"Our view of the pinwheel dust spiral from Earth absolutely looks face-on (spinning in the plane of the sky), and it seemed like a pretty safe assumption that the two stars are orbiting the same way," says astronomer Grant Hill of Keck Observatory in the US.

"When I started this project, I thought the main focus would be the colliding winds and a face-on orbit was a given. Instead, I found something very unexpected. The orbit is tilted at least 30 or 40 degrees out of the plane of the sky."

Wolf-Rayet stars are very massive, very hot, and very luminous stars at the end of their main-sequence lifespans. Because they are so massive – the 'death star' is around 13 solar masses – that lifespan is very short; WR 104 is around just 7 million years old.

The Wolf-Rayet stage of such a massive star's life involves the loss of mass at a very high rate, transported by the wild stellar winds, driven by radiation pressure in very hot, bright stars.

This can result in some of the most beautiful death scenes in the cosmos. The dust blowing away from Wolf-Rayet stars with a binary companion can become carved into spectacular shapes by the orbital interaction, like we see with WR 140 and Apep.

WR 104 is notable not just for the rarity of Wolf-Rayet stars in the galaxy, but also for the spiral shape its escaping dust forms as it leaks out into space. This is the result of the gravitational interaction with the binary companion, itself a very hot, massive, and luminous OB star orbiting with WR 104.

Hill and his colleagues used Keck observations dating back to 2001 to determine the nature of the interaction. Their analysis showed that the two binary stars share a circular orbit with a period of about 241.54 days, separated by a distance about twice that between Earth and the Sun.

Because the companion OB star is also massive – around 30 times the mass of the Sun – it, too, has a powerful wind driven by radiation pressure. As the two stars orbit, their winds collide, resulting in the production of dust that is heated by ultraviolet light. That heat is released as thermal emission, picked up by powerful infrared telescopes like those housed at the Keck Observatory.

But the biggest surprise was the orientation of the system. Previous models of WR 104 had it oriented so that the poles of both stars were directly pointing towards Earth. This is a perilous position for us, because when a Wolf-Rayet star explodes in a supernova, it should release a gamma-ray burst from its poles.

If the pole is pointed at Earth, the gamma-ray burst would erupt right at us, depleting our ozone layer and leaving us vulnerable to an extinction event. It's not clear exactly how far away WR 104 is, since its nature makes measuring its distance difficult. Estimates place it between around 2,000 and 11,000 light-years, the lower end of which is near enough to pose a hazard.

Well, it turns out we don't have to worry. Hill and his colleagues were able to determine that the system's orbital plane is tilted with respect to Earth, so any gamma-ray bursts would sail harmlessly off in another direction.

Of course, it's not projected to happen for another few hundred thousand years, but if we're going to be prepared for such an event, it's better to have all the cards sooner rather than later.

However, the find represents a new mystery. Although the stars' poles are not pointed towards Earth, the spiral does appear to be directly plane-side towards us, suggesting that the dust and the orbital plane are misaligned. We simply don't know how this could happen.

"This is such a great example of how with astronomy we often begin a study and the Universe surprises us with mysteries we didn't expect," Hill says.

"We may answer some questions but create more. In the end, that is sometimes how we learn more about physics and the Universe we live in. In this case, WR 104 is not done surprising us yet!"

The findings have been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.