In some glaucoma patients, vision loss mysteriously progresses despite treatment, and new research from China points to immune cells that migrate from the digestive tract to the eyes.

These "gut-retina axis" cells bind a specific protein and gain access to the eye's light-sensitive tissue, where they damage retinal ganglion cells (RGCs).

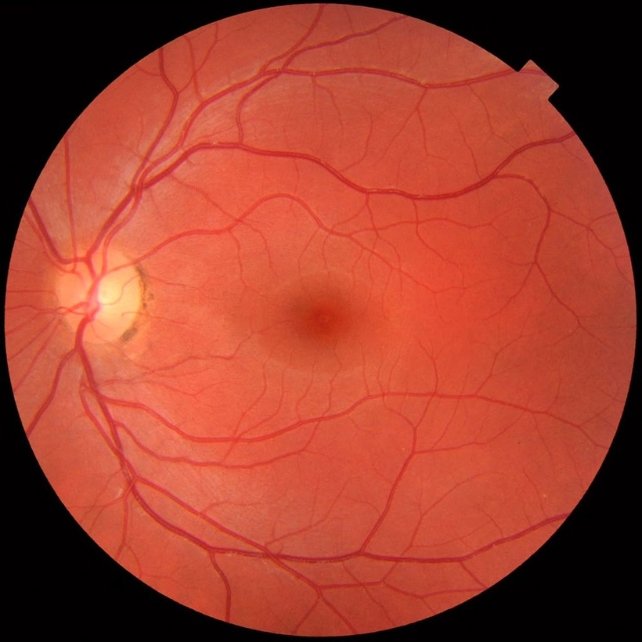

Glaucoma, classified as a group of neurodegenerative diseases, is an umbrella term for eye diseases caused by loss of RGCs, whose axons form the optic nerve which transmits visual information to the brain.

Your optic nerve is sending this to your brain's visual cortex to process right now, if you're reading with your eyes.

A leading cause of blindness, glaucoma is currently incurable; treatment aims to halt disease progression.

"Our findings emphasize the importance of the gut-retina axis in glaucoma pathogenesis and for the development of therapeutic strategies," the researchers write in their paper.

Pressure inside the eyeball, called elevated intraocular pressure (EIOP), is the main risk factor for glaucoma. Lowering EIOP is a primary goal of treatment, but it isn't always successful in stopping progression of the disease.

Previous studies hinted that immune system T cells may play a role in glaucoma damage, but the underlying mechanism has been unclear.

"T cells and other circulating immune cells are normally denied permission to enter the retina," notes the research team, led by clinical immunologists Chong He, Wenbo Xiu, Qinyuan Chen, and Kun Peng from the University of Electronic Science and Technology.

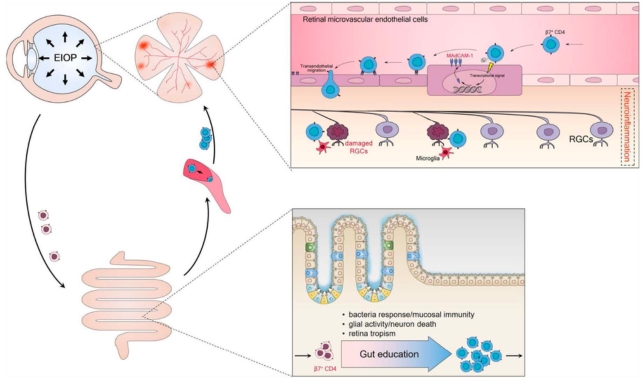

The four scientists were part of a 2021 study that found a subset of CD4+ T cells express a gut-homing receptor, integrin β7, which somehow gained entry to the retina with a little help from a protein called mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule 1 (MAdCAM-1).

In their new study, He, Xiu, and team confirmed a link between CD4+ T cells that express integrin β7, MAdCAM-1, and glaucoma disease severity in patients.

The first step was to test blood samples from 519 glaucoma patients and 189 healthy controls. A significantly higher percentage of β7-expressing CD4+ T cells was found in glaucoma patients compared to healthy controls, and glaucoma patients with more of these cells in their blood had more severe eye damage.

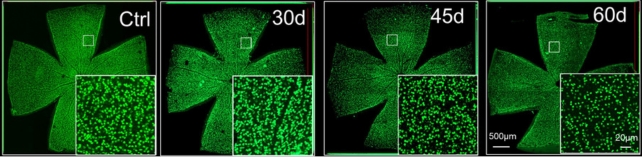

Using an EIOP-induced mouse model of glaucoma, researchers next showed that to gain access to the retina, β7+ CD4+ T cells in these early stage glaucoma mice must make a detour through the gut.

The team found the β7+ CD4+ T cells of EIOP-induced mice were reprogrammed in the gut, so they could use integrin β7 as a kind of license, returning to the blood circulation functionally equipped to travel to the retina.

While normal T cells are unable to bind to MAdCAM-1 in the retina, the gut-licensed cells were able to do so, allowing them access to the eye tissue, which "eventually led to neuroinflammation".

"The ability to induce MAdCAM-1 expression on retinal [vessels] might be one of the mechanisms whereby gut-licensed β7+ CD4+ T cells cross the blood-retina barrier and invade the retina," the team explains.

To investigate the link between these suspect cells and proteins and glaucoma damage, the team administered antibodies to mice that blocked the β7+ CD4+ T cells' interaction with MAdCAM-1. Inhibiting the communication with MAdCAM-1 significantly reduced the damage caused by glaucoma.

"Our study reveals a role of gut-licensed β7+ CD4+ T cells and MAdCAM-1 in retinal ganglion cell degeneration," the authors write.

It's unclear how EIOP increases levels of these β7+ CD4+ T cells in the blood and how they are reprogrammed in the gut, so more research is needed.

The team concludes that clinical studies could test whether the antibodies used in their study could treat glaucoma, and says their work also demonstrates the potential role of the immune system in diseases like glaucoma.

The study has been published in Science Translational Medicine.