Ancient footprints reveal that a thriving landscape 1.5 million years ago in what is now Kenya was able to accommodate two different species of hominin, living side by side.

As Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei – a direct ancestor and an ancestral relative of modern humans, respectively – lived their lives in the Turkana Basin, they left their footprints, impressed deep in the mud around the lake, probably with barely a thought.

Now, that ancient lakeshore is part of the Koobi Fora fossil site, and those footprints show, for the first time, two distinct patterns of hominin bipedalism in the same time and place.

"Their presence on the same surface, made closely together in time, places the two species at the lake margin, using the same habitat," says geologist and anthropologist Craig Feibel of Rutgers University in the US.

That "closely together in time" is no exaggeration. According to an analysis of the footprints led by biologist Kevin Hatala of Chatham University in the US, the prints at the site were made within hours of each other.

"Fossil footprints are exciting because they provide vivid snapshots that bring our fossil relatives to life," Hatala explains.

"With these kinds of data, we can see how living individuals, millions of years ago, were moving around their environments and potentially interacting with each other, or even with other animals. That's something that we can't really get from bones or stone tools."

Bones are one of the most intriguing remnants of the past, but in order to really learn about how other ancient humans lived, we need to investigate the other traces of their existence they left in their wake. This includes tools, but every now and again, Earth preserves the literal imprint of those who dwell on its surface.

We've known about the footprints at Koobi Fora since 2007, and they represent the oldest known example of hominins walking upright like we do today. They demonstrate the same long stride pattern, and the toe-off propulsion modern humans use.

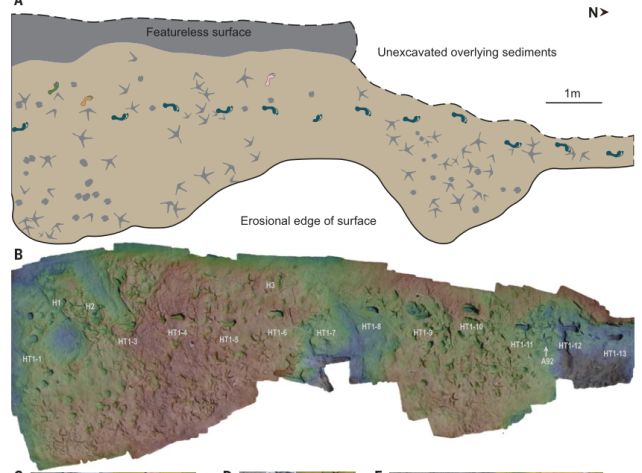

But since that 2007 discovery, more prints have been found at Koobi Fora – the most recent being in 2021, when deep, exquisitely preserved prints were discovered gouged out of what was once soft, squishy mud.

That mud had subsequently been covered by other layers of sediment over time, obscuring the prints, but the field team was able to excavate them in 2022 so that researchers could study them.

Hatala is an expert in foot anatomy. He and his colleagues conducted a detailed analysis of the prints at the site. They used two- and three-dimensional measurement techniques based on scans taken of the prints, and reconstructed the tread that was made to make the impressions.

Their results revealed that there are two distinct walking styles that can be inferred from the prints left in the rock – made by two different species of hominin, both known to have inhabited the site. Since the prints appear in the same sediment layer, they had to have been made at the same time.

And, since the two species are known to have had different diets and lifestyles, their competition with each other was likely low – meaning that the odds are good that they coexisted relatively peacefully.

The history of hominins on Earth was complex, and the relationships between species remain mostly mysterious. But a growing body of evidence – including the genetic material of Denisovans and Neanderthals lurking in our own DNA – reveals that hominin species were capable of living side-by-side.

The new research suggests that the emergence and evolution of bipedalism was just as complex as other aspects of the evolutionary history of hominins.

Skeletal remains of H. erectus and P. boisei are often found in the same geological layers and the Koobi Fora site, but bones can be moved around; it's not always easy to demonstrate sympatry based on bone evidence.

"This proves beyond any question that not only one, but two different hominins were walking on the same surface, literally within hours of each other," Feibel says.

"The idea that they lived contemporaneously may not be a surprise. But this is the first time demonstrating it. I think that's really huge."

The research has been published in Science.