The Solar System's little pocket of the Milky Way is, interestingly enough, exactly that. Our star resides in an unusually hot, low-density compartment in the galaxy's skirts, known as the Local Hot Bubble (LHB).

Why it's not called the Local Hot Pocket is anyone's guess; but, because it's an anomaly, scientists want to know why the region exists.

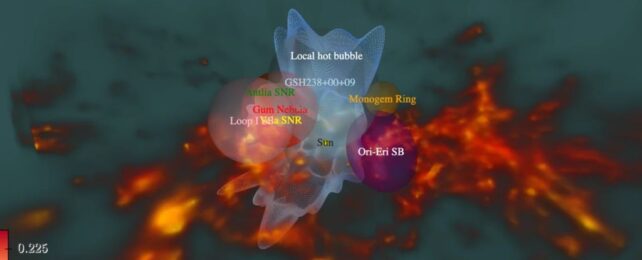

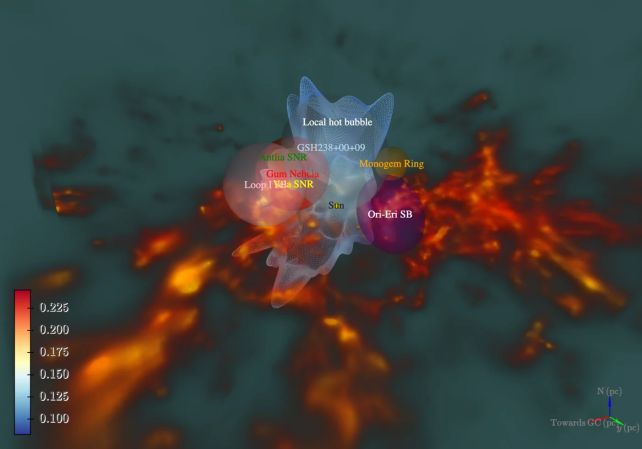

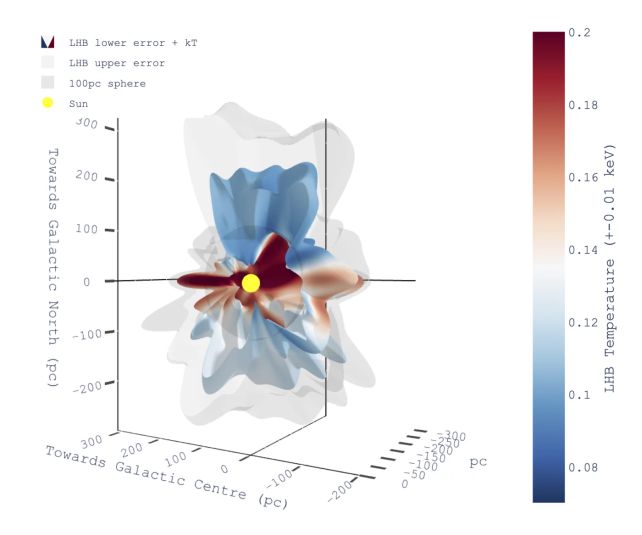

Now a team of astronomers has mapped the bubble, revealing not just a strange asymmetry in the pocket's shape and temperature gradient, but the presence of a mysterious tunnel pointing towards the constellation Centaurus.

The new data about the shape and heat of the bubble supports a previous interpretation that the LHB was excavated by exploding supernovae that expanded and heated the structure, while the tunnel suggests that it may be connected to another low-density bubble nearby.

The LHB is characterized by its temperature. It's a region thought to be at least 1,000 light-years across, hovering at a temperature of around a million Kelvin. Because the atoms are spread so thin, this high temperature doesn't have a significant heating effect on the matter within, which is probably just as well for us. But it does emit a glow in X-rays, which is how astronomers identified it, years ago.

But characterizing something you're physically inside is a lot easier to say than do. Imagine a fish (if a fish had human-like intelligence) trying to describe the shape of its tank without moving from the center. It's tricky – but with the right tools, it becomes easier.

This brings us to eROSITA, the Max Planck Institute of Extraterrestrial Physics' powerful space-based X-ray telescope. Led by astrophysicist Michael Yeung of the Institute, a team of researchers has made use of eROSITA to probe the LHB in greater detail than ever before.

We know, thanks to previous research efforts, that the LHB was likely the product of supernova explosions going off like a string of firecrackers, some 14.4 million years ago. The Solar System's position in the bubble's center is just a fun cosmic coincidence. But the LHB's shape remained poorly-defined – a sort of blobby, chubby knucklebone-like configuration.

One big advantage of eROSITA is its position. Wisps of our planet's atmosphere reach a surprising distance into space, with a large halo of hydrogen known as the geocorona extending as far as 100 Earth radii – over 600,000 kilometers (more than 370,000 miles) – from the surface. When particles blowing from the Sun interact with the geocorona, they create a diffuse X-ray glow very similar to the glow of the LHB.

eROSITA is aboard a space observatory positioned some 1.5 million kilometers from Earth. Sitting in a gravitationally stable position created by Earth's and the Sun's pull, the X-ray observatory is the first of its kind to observe the X-ray sky from completely outside of our glowing geocorona.

The researchers divided up eROSITA observations of the X-ray sky into around 2,000 sections, and painstakingly studied the X-ray light in each to generate a map of the LHB. Their findings revealed that the bubble is expanding perpendicular to the galactic plane, more than in a parallel direction. This is not unexpected, since the vertical directions offer less resistance than the horizontal.

The asymmetrical temperature gradient the researchers measured was consistent with the supernova theory for the bubble's creation, with the possibility that stars were exploding in our neighborhood until just a few million years ago.

Their map also refined the known shape of the LHB, allowing for a model to be constructed in three dimensions. The result resembles the outflows of what's known as a bipolar nebula, if a little spikier and bumpier. And there was a hidden surprise.

"What we didn't know was the existence of an interstellar tunnel towards Centaurus, which carves a gap in the cooler interstellar medium," says astrophysicist Michael Freyberg of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics. "This region stands out in stark relief."

We don't know, yet, what the tunnel connects to. There are a number of objects in the direction it trails off in, including the Gum nebula, another neighboring bubble, and several molecular clouds.

It could also be a clue that the galaxy consists of a whole connected network of hot bubbles and interstellar tunnels, an idea proposed in 1974, and for which little evidence has yet emerged. We might be on the brink of finding that network now – and this, in turn, could help us learn more about the recent history of our galaxy.

The research has been published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.