By sifting through pig faeces, scientists in Japan have discovered a new type of virus that could challenge the already complicated notions of how we categorise what viruses are, and what they can do.

Unlike living organisms that fall within the three 'domains of life' – bacteria, archaea, and eukaryota – viruses are fundamentally different because they don't have cells.

That lack of cellular anatomy makes them hard to classify from a biological standpoint, and even the question of whether viruses are actually alive or not has prompted much debate in scientific circles.

Despite all the ambiguity, though, there is some general agreement on what constitutes a virus: a particle made up of genetic material (nucleic acid), encased within a protective protein container that can infect some sort of cell and, once inside, replicate itself.

But the previously unknown virus uncovered by researchers from the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (TUAT) defies that interpretation.

"The recombinant virus we found in this study has no structural proteins," says virologist Tetsuya Mizutani from TUAT. "This means the recombinant virus cannot make a viral particle."

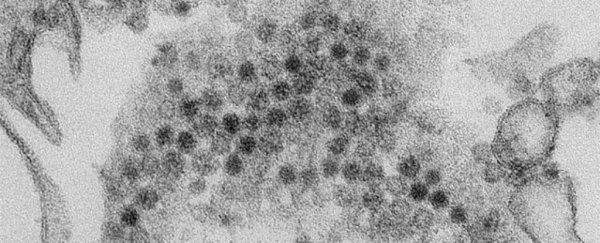

The team found this strange virus in pig faeces; it is a type of enterovirus G (EV-G), which belongs to the family of Picornaviridae.

Many types of EV-G have previously been identified by scientists, but in their new research, the TUAT team found a "novel defective" variant with unknown flanking genes in place of the viral structural proteins EV-G viruses usually exhibit.

According to the team, this means that the new discovery – called EV-G type 2 – wouldn't be able to invade a host cell on its own; if it can't do that, and therefore propagate itself, how does it exist at all?

One explanation, the team suggests in its new paper, is the defective recombinant EV-G might exploit another virus – called a 'helper virus' – which could lend viral structural proteins to help EV-G type 2 disseminate itself.

Possible evidence to back up that hypothesis was also found in the pig faeces analysed, in which similar amounts of type 1 and type 2 recombinant EV-G genomes were detected.

"Because the type 1 recombinant EV-G was detected in the same faeces sample as the new type 2 recombinant EV-G, this type 1 recombinant EV-G, which belongs to [a] different subtype, might have served as the helper virus," the researchers explain.

If so, how does this process occur? And if not, then how else is EV-G type 2 spreading, given it's unable, at least on its own, to infect cells, which is generally considered the singular vocation of viral kind.

Only a lot more research will be able to answer those questions, the team says, but the discoveries could again challenge our understanding of viruses on the whole. The researchers have even expressed some pretty strong claims in that direction.

"We may be facing an entirely new system of viral evolution," Mizutani says.

"We are wondering how this new virus came to be, how it infects cells or how it develops a viral particle. Our future work will be on solving this mystery of viral evolution."

The findings are reported in Infection, Genetics and Evolution.