Once containing a vast, prehistoric ocean, the Nullarbor Plain in southern Australia is an extraordinary landscape. Now a scrubby desert on limestone bedrock, it's extremely flat and almost featureless, extending for over a thousand kilometers.

But a new discovery suggests that the vast, semi-arid expanse may not be as featureless as we thought.

Using satellite imagery, an international team of scientists led by geologist Matej Lipar of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts has found an ancient landform that appears to have once been a coral reef – or part of one.

Although we know limestone can form from calcium carbonate from shells and fossils, and even though the Nullarbor limestone is rich with coral and algae fossils, there are no primary features associated with the deposition of carbonate.

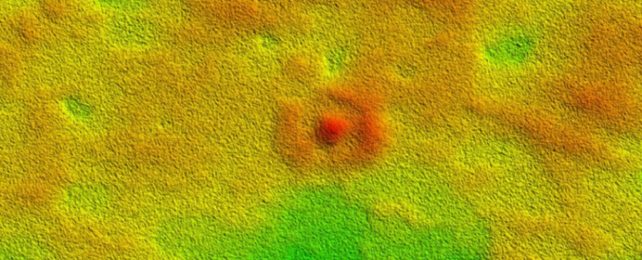

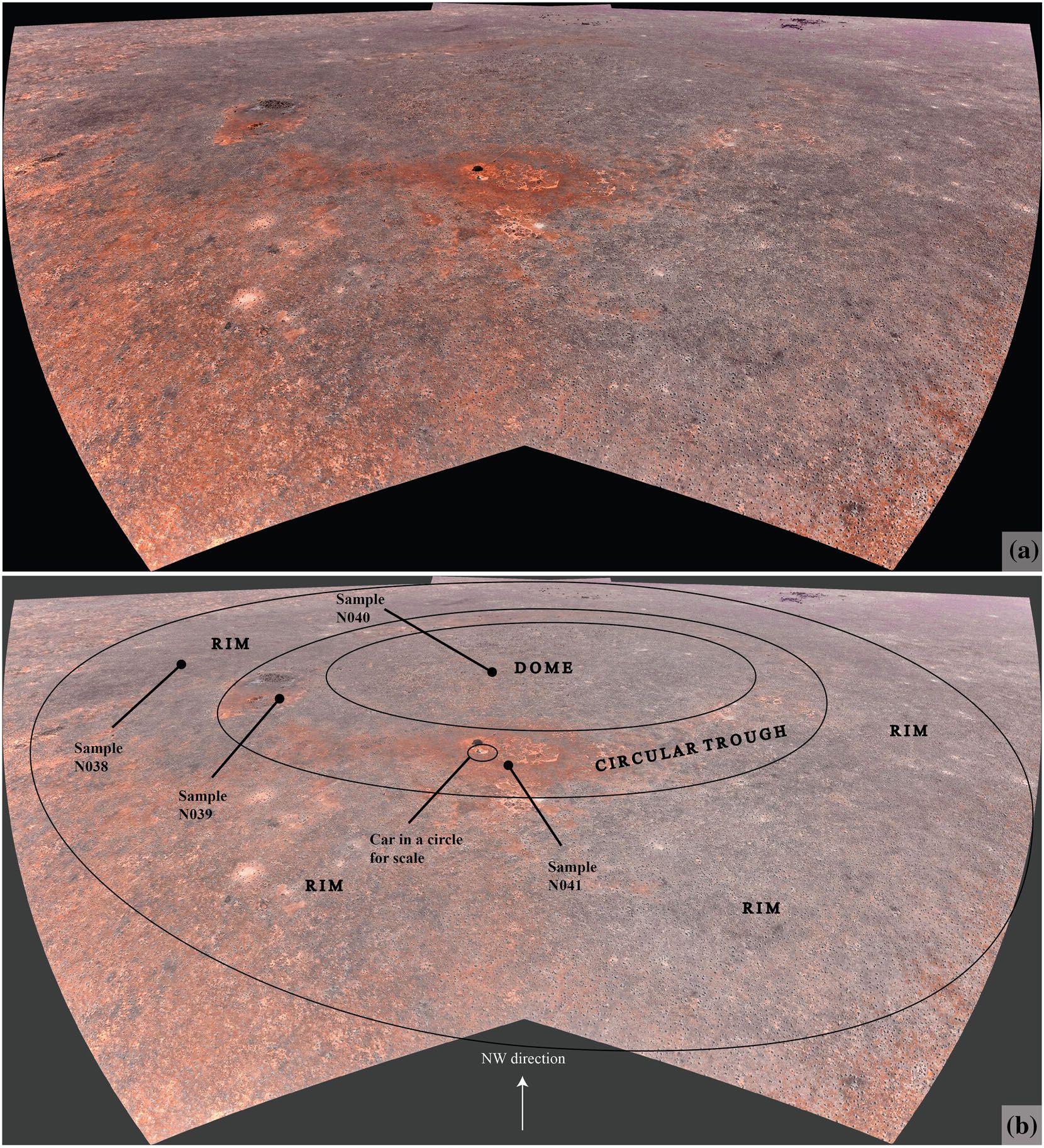

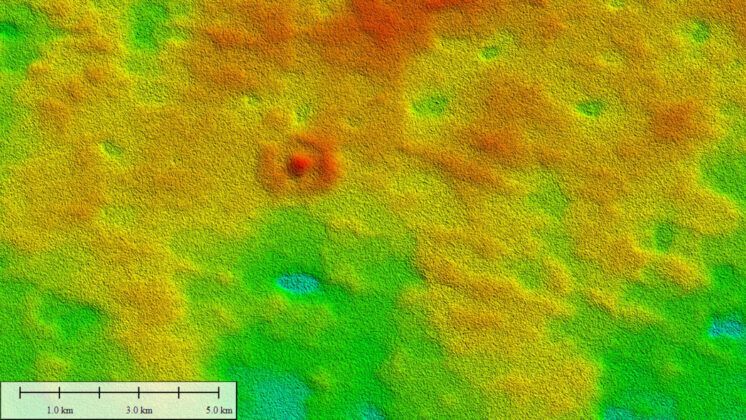

The reef-like landform consists of a circular elevated ring about 1,300 meters (4,265 feet) wide with a dome in the center, and it could be the first primary depositional structure ever discovered on the plain.

Unlike many parts of the world, much of the Nullarbor Plain has remained largely unchanged by weathering and erosion processes over millions of years, making it a unique geological canvas recording ancient history – and one certainly worth investigating, if you have the right tools.

"Through high-resolution satellite imagery and fieldwork we have identified the clear remnant of an original sea-bed structure preserved for millions of years, which is the first of this kind of landform discovered on the Nullarbor Plain," says geologist Milo Barham of Curtin University in Australia.

"The ring-shaped 'hill' cannot be explained by extra-terrestrial impact or any known deformation processes, but preserves original microbial textures and features typically found in the modern Great Barrier Reef."

Most of Australia is now arid and dry, with vast inland deserts. Millions of years ago, though, during the Miocene, the continent was teeming with life; not just dense, thriving forest ecosystems, but huge inland seas.

The ocean that covered the Nullarbor started to dry up around 14 million years ago, exposing the shallow-water limestones deposited during the middle Cenozoic.

Since that time, very little has happened on the plain, geologically speaking. There has been no significant sediment deposition to speak of, and no major upheavals leading to the formation of mountain ranges, or other features.

That means the Nullarbor is effectively a clean record of geological processes and features dating back to the Miocene.

"Evidence of the channels of long-vanished rivers, as well as sand dune systems imprinted directly into limestone, preserve an archive of ancient landscapes and even a record of the prevailing winds," Barham says.

"And it is not only landscapes. Isolated cave shafts punctuating the Nullarbor Plain preserve mummified remains of Tasmanian tigers and complete skeletons of long-extinct wonders such as Thylacoleo, the marsupial lion."

That's not all. "At the surface," adds Barham, "due to the relatively stable conditions, the Nullarbor Plain has preserved large quantities of meteorites, allowing us to peer back through time to the origins of our Solar System."

Only through the recent advances in high-resolution satellite imagery have scientists been able to discover some of the plain's more subtle features – including the reef-like structure.

Analysis of some of the rock taken from the limestone reveals fossilized benthic foraminifera, single-celled marine organisms. This finding is consistent with Nullarbor limestone.

But one of the samples revealed something interesting: microbial boundstone, a type of stone that was bound by coral or algae when it formed.

No other microbial boundstone has been identified in Nullarbor limestone, and this organism is capable of laying down organic material. Its presence suggests that the reef-like structure originates from the time when the limestone was deposited.

"These features," Barham says, "in conjunction with the millions of years old landscape feature we have now identified, effectively make the Nullarbor Plain a land that time forgot and allow a fascinating deeper understanding of Earth's history."

The research has been published in Earth Surface Processes and Landforms.