Ancient rocks excavated from a site inhabited by early humans some 1.4 million years ago may represent attempts at achieving perfect geometry.

Limestone spheroids from the 'Ubeidiya prehistoric site in Israel were deliberately shaped, archaeologists say, and show signs of improvement the more they were worked. This suggests that the creators had a specific goal in mind when they were carving, and that goal was very round.

This discovery doesn't bring us significantly closer to figuring out what the balls were used for, but it does show that there was a reason for creating them that way.

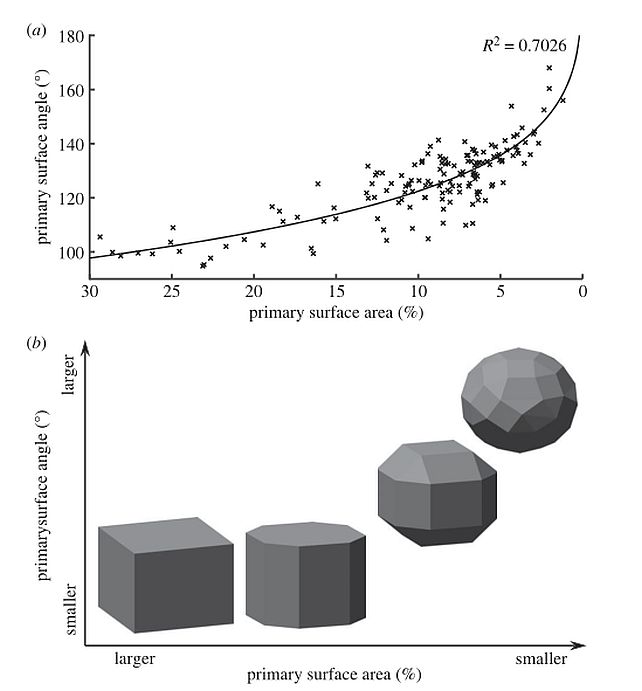

"During their manufacture, the spheroids do not become smoother, but they become markedly more spherical. They approach an ideal sphere, a feat that likely required skillful knapping and a preconceived goal," writes a team led by archaeologist Antoine Muller of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.

"The intentional production of sphere-like objects at 'Ubeidiya similarly shows evidence of Acheulean hominins desiring and achieving intentional geometry and symmetry in stone."

Spheroids are one of the fascinating puzzles of prehistory. They appear in sites across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East aged from around 2 million years ago, in varying degrees of sphericity. And we don't know what they were for.

Some studies suggest early humans used the spheroids as thrown projectiles. Other researchers speculate they may have been used to smash the marrow out of bones. However, their function remains ambiguous, in spite of extensive and thorough exploration of various avenues.

Rather than studying the specific function or functions the balls may have had, Muller and his colleagues decided to take a step backward. They investigated instead whether the balls were intentionally made, or an accidental by-product of manufacturing other tools.

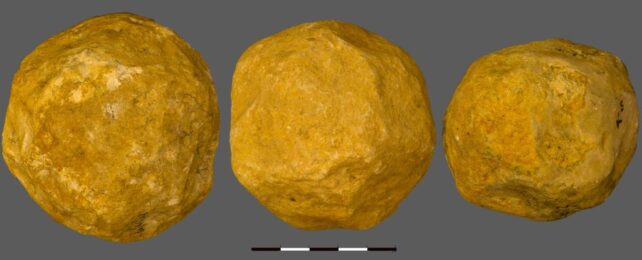

The research focused on 150 spheroids recovered from 'Ubeidiya. Dated to roughly 1.4 million years ago, they are the earliest known appearance of the objects outside of Africa, representing an unusually large collection from one site.

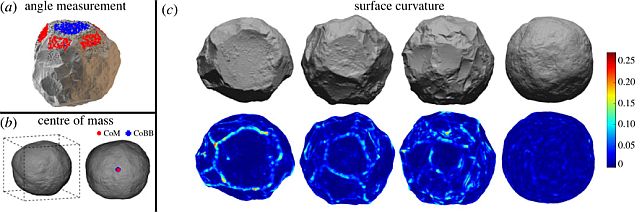

The team scanned in high resolution 3D, generating mesh models that they could analyze without damaging the original artifacts. They then used software to calculate the angles on the surfaces of the spheroids, where their centers of mass were, and the surface curvature of each ball. The researchers also used mathematical functions called spherical harmonics to reconstruct the shape of each spheroid, and performed an analysis of the scars on the surface of each spheroid to determine how they were created.

According to the data, the spheroids were knapped deliberately, their creators carefully removing material from precise points on the object's surface. The more surface that was chipped away, the rounder the balls grew.

The rocks did not, however, grow smoother, which the researchers attribute to intent.

"As surface curvature was uncorrelated with reduction intensity, the knappers at 'Ubeidiya did not desire a smooth, approximately round object," Muller and his colleagues write.

"Nor did they accidentally produce a smooth surface via intensive percussion. Instead, it appears that they attempted to achieve the Platonic ideal of a sphere and they approached this ideal following their spheroid reduction sequence."

Even without knowing what the spheroids were used for, the findings have important implications. They suggest a deliberate, cognitive process, and the skills to carry it out.

This, the researchers say, means the spheroids represent a complex formal technology, and the earliest known attempt at imposing symmetrical geometry on stone tools.

The research has been published in Royal Society Open Science.