Once thought to sense a drop in temperature, curious nerve-filled capsules discovered in both male and female genitals in the 1850s could play a far more arousing role in mammalian physiology.

Researchers from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in the US conducted experiments on mice to determine the role of structures found in the body's more delicate tissues known as Krause corpuscles.

Though yet to be peer-reviewed, the researchers' findings suggest the mysterious arrangements of nerves have nothing to do with reacting to the cold but actually specialize in transmitting mechanical vibration and 'light touches' to the central nervous system.

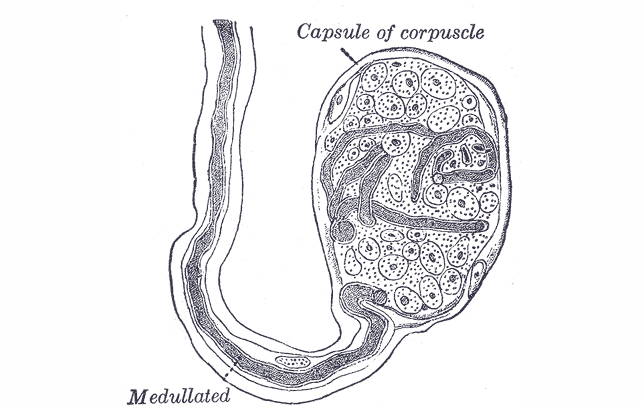

The structures were first described by the 19th-century German anatomist Wilhelm Krause as he dug into various tissues in the human body. Not only did he find them scattered throughout the glans and clitoris, but he saw them hiding in other tissues made up of skin and mucous cells, such as the lips and tongue and the eye's conjunctiva.

Krause noted the nerve-filled bodies he observed came in two types: one that resembled cup-and-stem-shaped structures in the kidney, which contained nerves with their axon 'tails' coiled up; and another that was cylindrical, with simpler arrangements of axons.

Though the physical details of these sensory corpuscles are clear, neither Krause nor anybody since could confirm what it is they actually do. Some textbooks maintain that they react to the cold, though evidence for any single function hasn't been convincing.

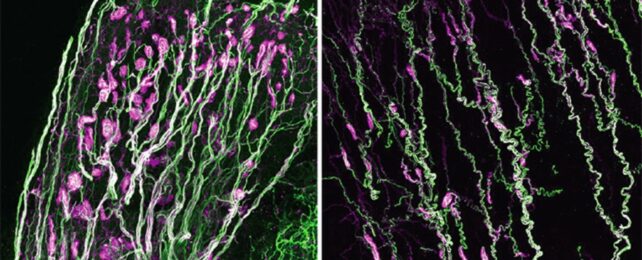

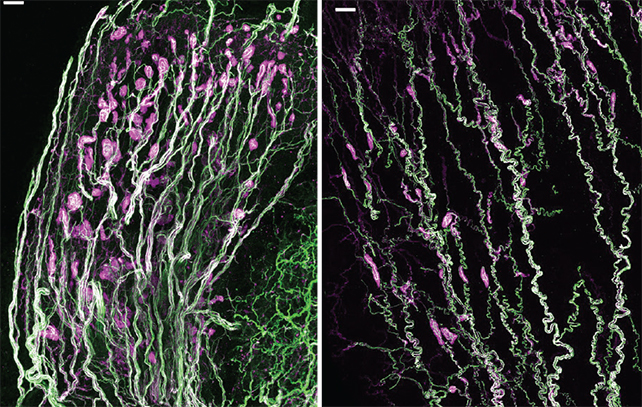

By staining sections of genital tissue from male and female mice, the researchers behind this latest investigation found that similar numbers of Krause corpuscles are in the penis and clitoris, though thanks to the glan's larger size, the bodies were spread out in a less concentrated fashion.

Genetic tools also allowed the team to finally determine precisely what the nerves buried inside these structures responded to. Technically speaking, the neurons inside the mouse Krause corpuscles exhibited low mechanical thresholds and rapid adaptation, phase locking to cycles of up to 120 hertz.

To put it in a way that's more suitable for pillow talk, it's mostly thanks to these tiny structures that light brushes and vibrations often feel so oh-so-good.

As for the corpuscle's speculative role in detecting chillier climes, the study found no signs of activity in response to dramatic shifts in temperature.

Based on these results alone, it's not unfair to imagine Krause corpuscles play a major role in sexual gratification in mammals. Stimulating the structures in restrained male mice – with mechanical and optogenetic attention – aroused them.

Meanwhile, mice genetically engineered to lack the nerve bundles showed no signs of arousal.

Interestingly, lacking the corpuscles didn't dissuade the male mice from looking for sex. Regarding the act itself, sex was somewhat curtailed, displaying shorter bouts of thrusting, delayed starts, or more interruptions.

As for the female mice lacking the critical structures, they simply weren't having it, displaying reduced to zero interest in sex even while their body was naturally cycling through estrus.

Though the analysis was all conducted on mice, it's a small leap to assume the structures serve similar roles in human anatomy. The discovery could have some exciting applications in better understanding sex drive and sensitivity in us, potentially informing research into treating various dysfunctions.

This research is available on bioRxiv.