Researchers say they have discovered what they call a "proto-writing system" embedded in 20,000-year-old cave paintings, making it the earliest form of some sort of writing we've ever found.

Hunters from the Upper Palaeolithic era would have used the symbols daubed on the walls to pass on essential survival information: The researchers suggest they show a record of animal mating seasons, organized by the lunar months.

It's a significant finding because it pushes back the earliest form of Homo sapiens writing by around 14,000 years.

Although we're not looking at letters and sentences here, these markings do represent "a complete unit of meaning", the researchers write in their published paper.

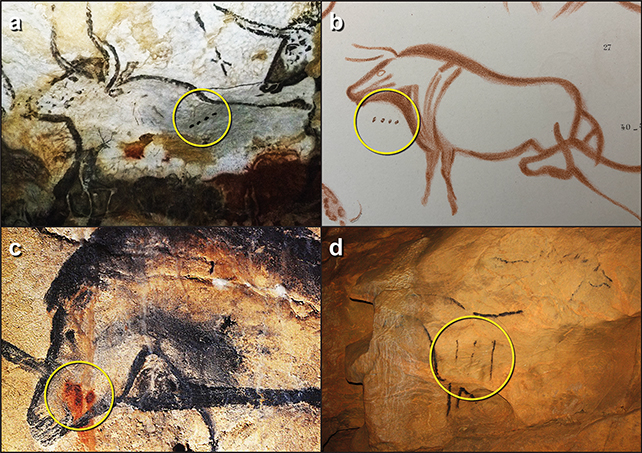

The team looked at more than 800 sequences of dots, lines, and Y shapes found in cave paintings across Europe from the last Ice Age.

These notations were often placed next to animals, which was crucial when it came to the process of decoding them.

"The meaning of the markings within these drawings has always intrigued me, so I set about trying to decode them, using a similar approach that others took to understanding an early form of Greek text," says independent researcher Ben Bacon.

The extensive database of painting samples was checked against the birth cycles of equivalent animals today as a reference, which revealed the previously hidden meanings of these marks – they were showing when each animal was mating.

It was hypothesized that the Y symbol that regularly appeared in these paintings stood for 'giving birth', offering the people of the time crucial information about these animals, which include wild horses, deer, cattle, and mammoths.

The discovery shows that these Ice Age hunters weren't just living day-to-day but also making records of past events to help them in the future, even if the calendar system that they applied here has since fallen out of use.

"Lunar calendars are difficult because there are just under twelve and a half lunar months in a year, so they do not fit neatly into a year," says mathematician Tony Freeth from University College London in the UK.

"As a result, our own modern calendar has all but lost any link to actual lunar months."

The work outlined by these researchers does involve some degree of interpretation and guesswork, and not everyone is convinced by the conclusion that we're looking at a mating season calendar here or in a form of what you could call writing.

Even the researchers behind the new study suggest that these markings are best thought of as an intermediary step between simpler notation and a complete writing system. At the very least, however, the idea is worthy of further investigation and study.

Writing as we know it today emerged from the Sumer region in Mesopotamia around 3,300 BCE, initially taking the form of basic pictographic shapes as letters. What we see here is that the history of scribbling on stone may go back much further.

"The study shows that Ice Age hunter-gatherers were the first to use a systematic calendar and marks to record information about major ecological events within that calendar," says archaeologist Paul Pettitt from Durham University in the UK.

"In turn, we're able to show that these people, who left a legacy of spectacular art in the caves of Lascaux and Altamira, also left a record of early timekeeping that would eventually become commonplace among our species."

The research has been published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal.