Hidden deep in the Pacific Ocean – almost 6,000 meters (19,685 feet) down into the Mariana Trench – are a group of hydrothermal vents, which could provide some vital clues as to how life got started on Earth.

That's the conclusion of a new study led by a team from the Riken Scientific Research Institute and the Tokyo Institute of Technology in Japan, and what makes this group of hydrothermal vents notable is the way they're able to produce energy without any help from living cells.

The scientists found nanostructures around the vents that can act as selective ion channels, which means they work a bit like underwater filters – letting certain types of charged particles through while blocking others.

Through this selection, a tiny but significant difference in voltage can be produced, not unlike organic channels in the membranes of our own cells. That no organic material is involved in this case suggests that energy generation – known as osmotic energy conversion – could have been established on Earth before life was, providing a suitable environment for living cells to come into being.

"The spontaneous formation of ion channels discovered in deep sea hydrothermal vents has direct implications for the origin of life on Earth and beyond," says biochemist Ryuhei Nakamura, from Riken.

Hydrothermal vents are weak spots where magma-heated water, which has seeped into Earth's crust, re-emerges into the ocean. This recycled water is packed with minerals and full of energy, which is why scientists think deep sea hydrothermal vents could play a role in the origins of life.

The vents considered in the current study are made of a complex mix of minerals, which makes them particularly interesting for research.

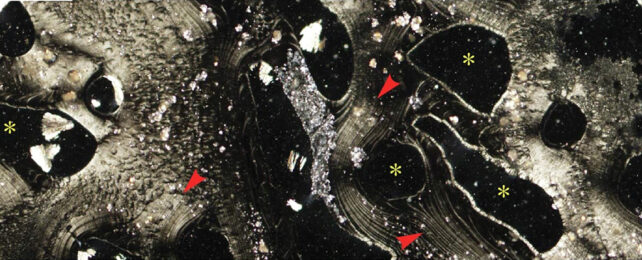

A close look at an 84-centimeter (33-inch) sample of magnesium hydroxide showed crystals organized in straight channels, controlling the flow of the liquid passing through the vent and creating a difference in voltage across the surface.

"Unexpectedly, we discovered that osmotic energy conversion, a vital function in modern plant, animal, and microbial life, can occur abiotically in a geological environment," says Nakamura.

Beyond the origins of life, the findings could help with blue energy harvesting – a power plant process where osmotic energy is used to generate electricity from the differences between saltwater and freshwater. By taking a few tips from nature, we might be able to improve the efficiency, affordability, and eco-friendliness of these techniques.

Most significantly though, it gets us closer to answering the question of how organic life can spring from inorganic materials – and how this might have happened on Earth, billions of years ago. Scientists have a lot of different ideas about the origins of life, but hydrothermal vents could certainly have been involved.

"In particular, our study shows how osmotic energy conversion, a vital function in modern life, can occur abiotically in a geological environment," says Nakamura.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.