By shifting a little focus from space to Earth, NASA is helping ecologists protect endangered species like tigers and elephants with its powerful satellites.

Habitat loss is currently the greatest threat to species on our planet. As human populations explode in number, we are altering more wilderness and using an ever greater share of resources. Larger species, like tigers and elephants, are some of the most vulnerable to extinction.

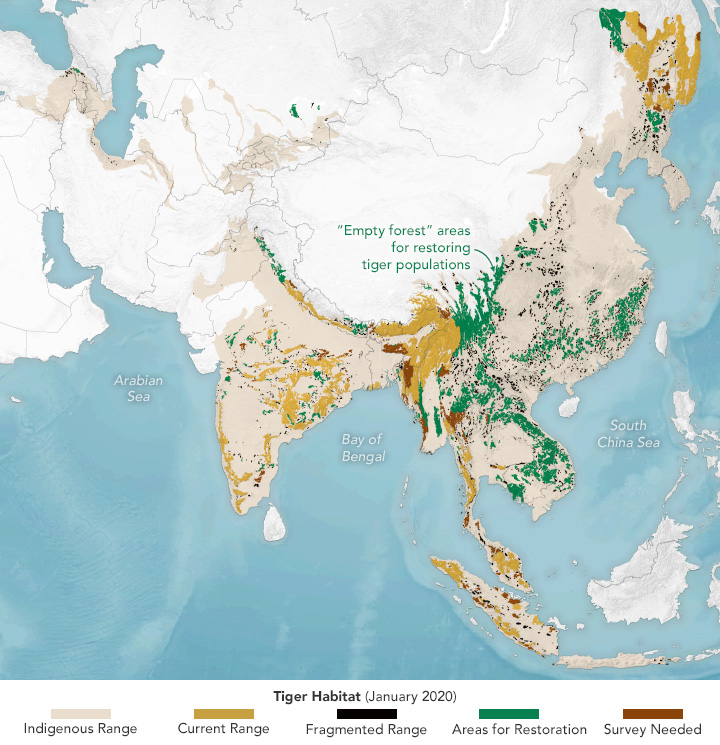

Once widespread across Asia, tigers (Panthera tigris) have lost a staggering 93 percent of their habitat over the past 150 years. Scientists estimate less than 4,000 of these majestic predators are alive today.

But NASA's satellite data reveals there's cause for hope, identifying suitable habitat for these vital predators, which they were not currently accessing.

"There's still a lot more room for tigers in the world than even tiger experts thought," conservation ecologist Eric Sanderson, now at the New York Botanical Garden, told Emily DeMarco at NASA. "We were only able to figure that out because we brought together all of this data from NASA and integrated it with information from the field."

This NASA data includes infrared and spectroradiometer imaging – which can monitor vegetation health from above in almost real time. Along with geographic mapping, and historic ground-based field work, Sanderson and colleagues were able to identify potential habitat that tigers can migrate or be reintroduced into.

"We find significant potential for restoring tigers to existing habitats, identified here…," Sanderson and team explain. "If these habitats had sufficient prey and were tigers able to find them, the occupied land base for tigers might increase by 50 percent."

Other researchers at NASA used similar techniques to map the changing habitat of Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) in southern Bhutan. Elephants are essential to the functioning of forests, yet they also face shrinking habitat that is exacerbating their conflicts with humans.

That team integrated data on habitat suitability and movement resistance to identify the most suitable corridors between elephant protected areas. These habitats have the potential to alleviate human-elephant conflicts.

NASA is also working to develop satellite based strategies to protect vast areas of public US land under the stewardship of the Bureau of Land Management. Their aim is to protect the Mojave desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii, endangered), greater sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus, at risk) and bighorn sheep (Ovis Canadensis, at risk).

Previously, conservation scientists have had to rely on slow, expensive and logistically challenging groundwork to obtain much smaller snapshots of habitat and movement data. NASA's satellites capture this information at a vastly greater scope at near real time scale, giving wildlife biologists the unprecedented chance to respond to threats much faster and more efficiently than ever before.

"Satellites observe vast areas of Earth's surface on daily to weekly schedules," says NASA biogeographer Keith Gaddis. "That helps scientists monitor habitats that would be logistically challenging and time-consuming to survey from the ground – crucial for animals like tigers that roam large territories."

The tiger research was published in Frontiers in Conservation Science.