California is a land shaped by seismic activity. A history of earthquakes is written in its landscape in the form of rifts, folds, and cracks. But major tremors also tend to leave less dramatic fingerprints.

While two of the most recent earthquakes to strike the state's south damaged infrastructure and land, they also warped the crust in ways so subtle, we need the kind of orbiting survey technology used by NASA to see them.

Amid last week's Independence Day celebrations, a 6.4 magnitude tremor shook the ground a couple hundred kilometres (about 150 miles) northeast of Los Angeles. A day later, an even bigger one hit, measuring 7.1 on the Richter scale.

These were two of the biggest quakes the south has seen in decades. It's not surprising they not only tore apart infrastructure, but also left their mark as ruptures in the planet's surface.

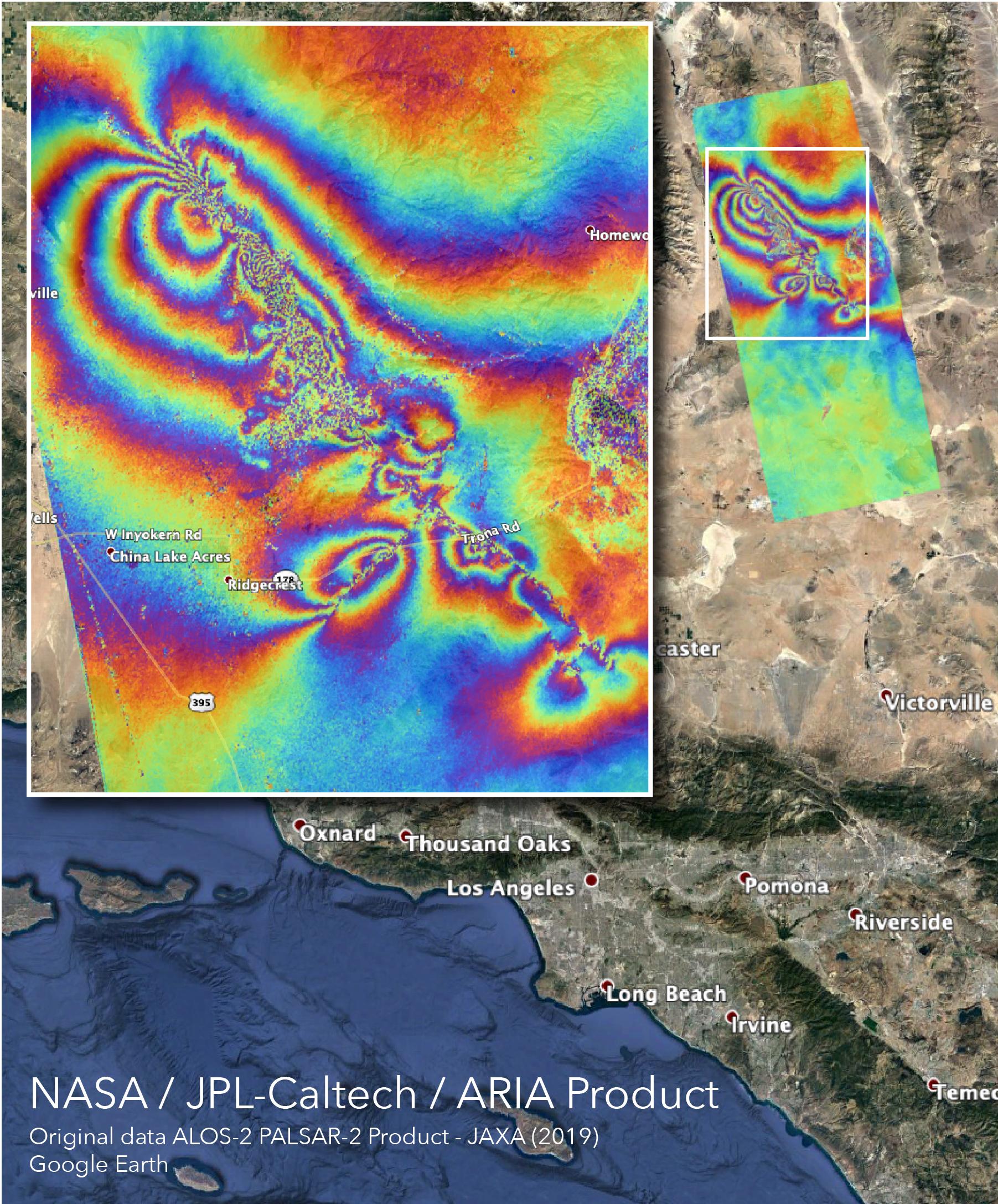

To get a better idea of less obvious changes to the crust caused by the quakes and thousands of their aftershocks, NASA's Advanced Rapid Imaging and Analysis (ARIA) team used data collected by a synthetic aperture radar, a device that produces high-resolution remote sensing imagery.

From its position on a satellite launched by the Japanese space agency JAXA, it uses its motion to pick up fine details in the landscape in two and three dimensions. Images taken of the landscape before the quakes were compared with those after, resulting in a map of the changes in surface elevation on a scale of just centimetres.

Different colours were then applied to highlight these minute displacements over a wide area, resulting in a spectrum of waves that would be impossible to see from ground level.

Each colour in the image below represents 12 centimetres (about 4.8 inches) of lifting or sinking in the landscape, with evidence of cracks in the lines cutting through the fringes of some colours.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The map could be a useful way to identify regions that are likely to contain damage yet to be discovered, such as broken pipes or isolated roads, or even landslides just waiting to topple.

It's fortunate that the epicentre of each quake was in a remote area. No deaths were reported, in spite of their impressive power.

But that isolation doesn't make them any less of a threat to those who live out in California's remote east.

They occurred in what's known as Eastern California's shear zone; a crackling field of faults caused by the tectonic movements further west that stands apart from other fault zones, both physically and figuratively.

While researchers have a pretty good grasp on the boundaries between plates, these loosely connected troughs of faults are less explored.

The Independence Day quake reflected the odd nature of the area, resulting from a simultaneous shift in two faults crossing at right angles. Data such as this could help add important information to the complex nature of the system.

While the state anxiously awaits a jump in the San Andreas fault to shake up major cities, these recent quakes remind us it's not the only show in town.