According to NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), scientists have, for the first time, produced proof that the recovery of the ozone hole is attributable to human action.

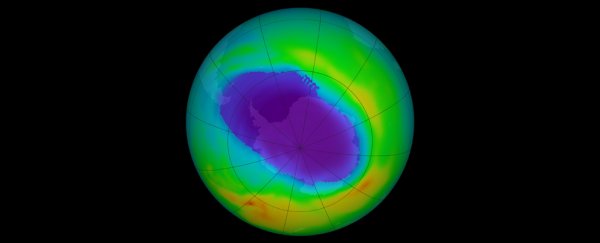

Every September, the Antarctic ozone hole forms after rays from the Sun catalyse ozone destruction cycles.

These cycles involve chlorine and bromine, which mostly come from chlorine-containing human-made chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which were banned in 1996.

Past research on the ozone has focused on the hole's size, but for their research, the GSFC team actually measured the chemical composition within the ozone hole.

Using the Microwave Limb Sounder (MLS) aboard the Aura satellite, the researchers were able to measure hydrochloric acid, which is created when chlorine, after it destroys almost all available ozone, reacts with methane.

They concluded that chlorine levels declined by approximately 0.8 percent each year and noted a 20 percent decrease in ozone depletion in the Antarctic winter than there was in 2005.

"We see very clearly that chlorine from CFCs is going down in the ozone hole, and that less ozone depletion is occurring because of it," said Susan Strahan, the study's lead author and an atmospheric scientist at GSFC, in a news release.

The study has been published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Eliminating CFCS

Two years after the Antarctic hole was discovered in 1985, a number of nations signed the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, a series of regulations that took action against ozone-depleting compounds.

Later, amendments were added to the protocol to entirely phase out the production of CFCs, and the researchers attribute the decrease they observed to this international ban.

"[The 20 percent decrease] is very close to what our model predicts we should see for this amount of chlorine decline," said Strahan.

"This gives us confidence that the decrease in ozone depletion through mid-September shown by MLS data is due to declining levels of chlorine coming from CFCs."

While promising, the battle to reverse the damage we've done to the planet is far from over.

"CFCs have lifetimes from 50 to 100 years, so they linger in the atmosphere for a very long time," said Anne Douglass, a fellow GSFC atmospheric scientist and the study's co-author.

"As far as the ozone hole being gone, we're looking at 2060 or 2080. And even then there might still be a small hole."

Still, these recent findings on the ozone hole's size are a reminder that significant action can have a significant impact.

Climate change can seem like a problem too massive to realistically tackle, but if we can reduce ozone depletion in Antarctica through the relatively simple measure of eliminating CFCs, there is no telling what else we could accomplish.

This article was originally published by Futurism. Read the original article.