For its newest planetary science mission, NASA aims to land a flying robot on the surface of Saturn's moon Titan, a top target in the search for alien life.

Dragonfly will be the first endeavor of its kind. NASA's car-sized quadcopter, equipped with instruments capable of identifying large organic molecules, is slated to launch in 2026, arrive at its destination in 2034 and then fly to multiple locations hundreds of miles apart.

"The science is compelling . . . and the mission is bold," Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA's associate administrator for science, said Thursday.

"I am convinced now is the right time to do this."

Why Titan?

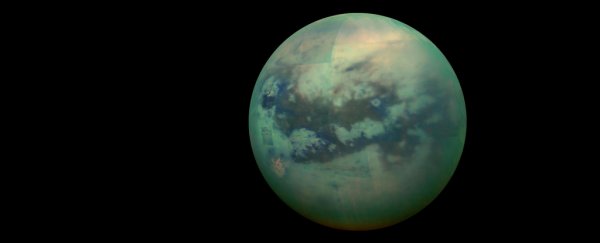

Titan is bigger than the planet Mercury and as geographically diverse as Earth. This large, cold moon features a thick, methane-rich atmosphere, mountains of ice and the only surface seas in the solar system beside those on Earth.

But on Titan, the rivers and lakes are full of sloshing liquid hydrocarbons. If the moon does harbor water, scientists think it exists in an ocean lurking beneath the frozen crust.

It's a world utterly unlike our own, and yet "we know it has all of the ingredients that are necessary to help life form," said Lori Glaze, NASA's planetary science division director.

Titan's complex rings and chains of carbon are fundamental to many basic biological processes and may resemble the building blocks from which life on Earth evolved.

Dragonfly will provide "the opportunity to discover the processes that were present on early Earth and possibly even the conditions that might harbor life today," Glaze said.

New Frontiers

This is the fourth mission to be funded as part of NASA's New Frontiers program, which supports medium-size planetary science projects that cost less than US$1 billion.

It follows in the footsteps of the New Horizons spacecraft, which flew past Pluto and the Kuiper belt object MU69; the asteroid-explorer OSIRIS-REx; and the Juno probe currently orbiting Jupiter.

It was one of two program proposals that have been under consideration since December 2017. The other finalist was the CAESAR mission, for Comet Astrobiology Exploration Sample Return, which would have circled to the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

That craft would have rendezvoused with the huge space rock, sucked up a sample from its surface and returned it to Earth in November 2038.

(NASA)

(NASA)

Dragonfly will land near Titan's equator, among dunes composed of solid hydrocarbon snowflakes. It will be powered by heat from radioactive plutonium, much like NASA's intrepid Mars rovers.

But with eight rotors, it will be able to cover much more distance than any wheeled robot ever has - as many as nine miles per hop.

"It's actually easier to fly on Titan," Elizabeth Turtle, the mission's principal investigator and a researcher at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, said during a news conference Thursday. That world's atmosphere is thicker than Earth's and its gravity is weak.

The craft has to be able to maneuver on its own, however. Light signals from Earth take 43 minutes to reach Titan, making Dragonfly much more complicated than a standard drone.

Scientists had to develop a navigation system that will enable the spacecraft to identify hazards and fly and land autonomously.

Where will Dragonfly land?

In flight, it will sample Titan's hazy atmosphere and provide aerial images of the landscape below. But the craft will spend most of its time on the ground, testing for biologically relevant materials.

Its ultimate destination is Selk Crater, the site of an ancient meteor impact where scientists have found evidence of liquid water, organic molecules and the energy that could fuel chemical reactions.

The gutsy design prompted NASA to ask two independent teams to examine the mission plan and assess whether the project could be executed at the cost allowed, Zurbuchen said. Ultimately, the agency decided the project was doable.

"While this is a new way of exploring a different planet, this is actually technology that is very mature on Earth," Turtle noted.

"Really what we're doing with Dragonfly is innovation, not invention."

NASA hasn't seen the surface of Titan since 2005, when the Huygens probe dropped through its hazy orange clouds to reveal an outlandish panorama. Every Earth-like feature on this strange moon had a chemically alien twist.

"Instead of liquid water, Titan has liquid methane," scientists reported in the journal Nature. "Instead of silicate rocks, Titan has frozen water ice. Instead of dirt, Titan has hydrocarbon particles settling out of the atmosphere."

At nearly 1 billion miles from the sun, its world is bitterly cold; temperatures average minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit (-180 degrees Celsius) on a mild day. Were more oxygen present, those abundant hydrocarbons (the main component of gasoline) would quickly catch fire.

The presence of all that methane — a molecule that is usually destroyed by sunlight in a few million years - is what's most intriguing to scientists. Its persistence suggests some process that is continually renewing Titan's supply.

They now believe that Titan experiences a weather much like what occurs on Earth - except its clouds are made of hydrocarbon gas, and its precipitation falls as organic compound rain and snow.

Life as we don't know it

Turtle said Thursday that Titan in many ways resembles the infant Earth, before life evolved and irrevocably changed the planet.

"Titan is just a perfect chemical laboratory to understand the chemistry that occurred before chemistry took the step to biology," she said.

Johns Hopkins University planetary scientist Sarah Hörst, a member of Dragonfly's science and engineering team, once compared Titan to a cosmic kitchen in which scientists have found all the ingredients for life.

"But you weren't there when they got mixed, so you don't know what they got mixed up to do. You don't know what will happen when you bake it," she said in 2017.

All those ingredients may add up to nothing. Or they could be signs of "life as we don't know it," she said - a form of biology based in hydrocarbons, rather than water.

In the years since the Huygens landing, scientists have detected even more molecular riches: negatively charged molecules associated with complex chemical reactions; rings of hydrogen, carbon and nitrogen from which amino acids can be built; and molecules that can clump together to form a spherical envelope much like the membranes that surround cells.

"We are pretty darn sure that everything in these broad, big-picture categories that's required for life exists on Titan," Hörst said. "At some point it just comes down to, well, shouldn't we go check?"

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.