NASA's two STEREO probes have been able to image the Sun's outer edge for the first time, giving us an important look at how solar winds are formed – winds that can have a major impact on life on Earth.

In particular, it gives astronomers a new understanding of how the Sun's steady corona rays (in the Sun's upper atmosphere) transition into gusty and turbulent winds as they leave the star and head out into space.

STEREO – aka the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory – is a solar observation mission launched in 2006 to map the Sun and its surrounding atmosphere in more detail than ever before.

Two almost identical spacecraft have been sent out to provide stereoscopic, 3D imagery, and these new processed solar wind graphics are the latest pictures to be revealed.

As the video below demonstrates, NASA scientists have discovered a distinct boundary some 32 million kilometres (20 million miles) out from the Sun's surface, between where the corona rays end and the solar winds begin.

"Now we have a global picture of solar wind evolution," said one of the lead researchers, Nicholeen Viall from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre. "This is really going to change our understanding of how the space environment develops."

What appears to happen is that once you've moved out a certain distance from the Sun, the influence of the star's magnetic field ends – meaning the flow of plasma emanating from the Sun becomes more turbulent. It's a bit like the way spray expands from a water gun, according to NASA.

That hypothesis has been around for a while, but these are the first observations to back it up – taking photos and videos of the Sun's outer edge is no easy task, and scientists had to develop a complex algorithm to make the solar wind particles bright enough to view.

These image processing computations had to get rid of background noise and light sources – sources that were in some cases more than a hundred times brighter than the solar winds NASA was trying to identify.

In other words, it's a little bit like trying to spot stars in the sky above a major city, where fainter, distant lights get lost in the ambient glow of modern life.

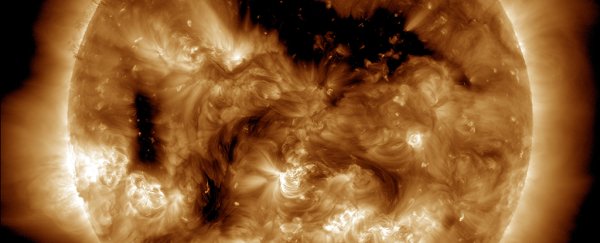

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre

"As you go farther from the Sun, the magnetic field strength drops faster than the pressure of the material does," explained solar physicist Craig DeForest. "Eventually, the material starts to act more like a gas, and less like a magnetically structured plasma."

And if we can understand more about how solar winds begin their journey, then we can understand more about how the Sun affects everything else in the Solar System.

It's thought solar winds could be powerful enough to strip a planet of life, and severe solar storms can damage satellites and power lines here on Earth.

In light of how devastating they can be, the more we know about solar winds – and the forces that generate them – the better.

The findings have been published in The Astrophysical Journal.