Solar System exploration isn't what it used to be. In the old days, various government agencies did all the space exploring. The 12 people who walked on the moon relied on government-run transportation.

Now we're in the era of New Space, and entrepreneurs want to race ahead to the moon and Mars on private spacecraft. Elon Musk wants to build cities on Mars.

NASA, meanwhile, has its own aspirations for human missions to Mars, first to orbit the Red Planet and later to land, beginning in the 2030s.

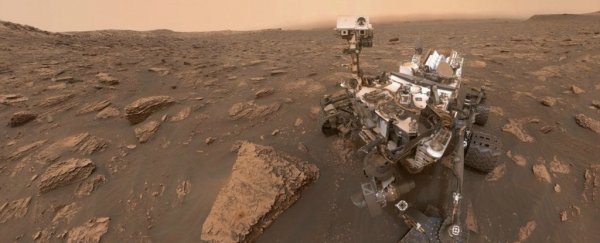

NASA also is slowly putting together a robotic sample-return project, which will begin when the next rover to reach Mars scoops up samples of the Martian surface to be launched back to Earth sometime in the future.

All this raises the sticky issue of "planetary protection".

To adhere to the principle of planetary protection, any spacecraft going to Mars, or to any other destination where conditions for life might exist, should not contaminate that environment with our terrestrial microbes.

The reverse is also true: Don't unwittingly bring back alien microbes to Earth.

A report released Monday by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine is urging NASA to improve its planetary protection process in light of the new players in space exploration and the prospect of major missions to Mars and the moons of the outer solar system.

"This process needs to begin now," said Joseph Alexander, a space consultant who chaired the committee that wrote the report.

"If people go to Mars in 2030s, it's not too early now to be prepared."

The advocates for human missions to Mars have sometimes viewed planetary protection as a hindrance.

But it's also the law: The Outer Space Treaty of 1967, an international agreement, states that signatories will do their exploration of other worlds in a manner "to avoid their harmful contamination, and also adverse changes in the environment of the Earth resulting from the introduction of extraterrestrial matter."

Alexander said no government agency in the United States has the authority to regulate the actions of private companies putting hardware on other worlds. The Federal Aviation Administration regulates launches and landings but not the payloads.

Entrepreneurs will embrace a clear regulatory regime, said Norine Noonan, a professor of biological sciences at the University of South Florida at St. Petersburg, who was on the National Academies committee.

"What does the regulated community want? They want certainty. They want predictability. They want to be told this is what you have to do," she said.

In terms of planetary protection, she said, "NASA really does not have a plan, right now, for human missions to Mars. . . . Once you start sending humans to other worlds, the game changes. Because you have to bring people back. Humans are spewing fountains of viruses and bacteria. We have more bacteria on the surface of our body than cells in our body."

No one knows if there is life on Mars. It's not obviously an abode of life, but life is amazingly adaptable, and there could be Martian organisms lurking in aquifers.

One good reason to enforce planetary protection rules is for scientific credibility. NASA does not want the search for life on Mars to be fouled up by stowaway microbes from Earth.

"Earth organisms could completely sully what's there and compromise the science," said Gary Ruvkun, a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and a member of the National Academies committee.

That said, he thinks the planetary protection policies have been too restrictive.

For example, fear of contaminating a location of biological interest on Mars or a moon in the outer planets could inhibit where a spacecraft could land or where a rover could explore.

"It inhibits the ability to explore. It naively thinks that if you have some bacteria on a spacecraft, they're just going to grow like crazy and mess up the next planet over," he said.

"I find it kind of laughable. It's kind of a '50s ideology."

He also thinks it's extraordinarily unlikely that a Martian organism brought to Earth would wreak havoc.

"The chances of some organism that's evolved to love Mars to suddenly say, 'Gosh, I'm going to kill off kangaroos' - it ain't gonna happen," he said.

"The pathogenesis is a highly evolved trait. There's been a billion years of evolution that makes a pathogen a pathogen."

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.