NASA's Cassini spacecraft has successfully completed its flyby of Saturn's moon Enceladus, cruising 49 kilometres (30 miles) above the moon's south pole just a few hours ago. While images of its first ever icy plume dive will take up to 48 hours to retrieve, the Cassini team will already be receiving data collected during the encounter.

"Although the October 28th fly-by won't be the closest we've ever been to Enceladus, it is the closest flyby over the south pole and through the plume," said Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker. She added that the encounter will allow them to explore a region of the plume that's never before been sampled.

Launched in 1997, the Cassini spacecraft has been orbiting Saturn since 2004, providing us with the most stunning images of the planet's iconic rings, while answering researchers questions about its atmosphere and magnetic field. Now it's focussing in on Enceladus, and for good reason.

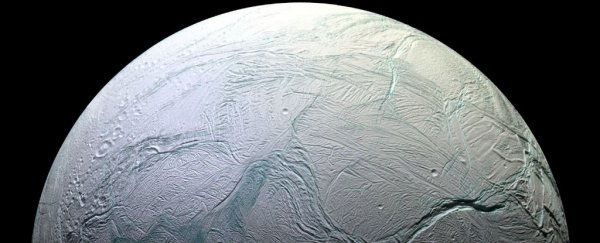

As Maddie Stone puts it so well over at Gizmodo: "It's a brilliant white snowball. It's got a global ocean beneath its surface. It's got freakin' ice volcanoes. Best of all, based on samples collected during today's historic flyby, we might soon know if Enceladus is habitable."

It's arguably the prettiest moon we've ever seen, and there's so much going on beneath that powder-white exterior streaked with turquoise tiger stripes. While NASA has made clear that Cassini is not capable of detecting signs of life, it can still tell us a whole lot about Enceladus, including how likely it is that it's habitable. Here are a few things they'll be looking for in the data:

1. Confirm presence of molecular hydrogen (H2)

If we can find this, we'll have evidence that that hydrothermal activity is going on in Enceladus's ocean, thanks to hydrothermal vents on the seafloor. Scientists will be able to figure out how much heat and energy is being produced by these vents, and whether or not these could be conducive for life.

"It is in such ocean vents that some of the most primordial-looking life-forms have been found on our own planet," Dennis Overbye writes for The New York Times. "What the Cassini scientists find out could help set the stage for a return mission with a spacecraft designed to detect or even bring back samples of life."

2. Better understand the chemistry of material in the plume

Cassini's dust collector will have gotten close enough to the source of the plume to pick up a few of the heavier particles that have been flung into the atmosphere. Among these particles, scientists will be looking for complex organic molecules that perhaps originated in the moon's sub-surface ocean.

3. Determine the nature of the plume source

The question here is if the plume shoots out in thin, column-like jets, or if it's spread out in curtain-like eruptions that run along the length of the tiger stripe fractures. Maybe it's a bit of both? Scientists will also be looking at data from Cassini to figure out how much icy material it's spraying into the atmosphere - the spacecraft's high-rate detector instrument can count 10,000 individual ice particles a second in real time. Knowing this will help them to figure out how long the moon's been active.

Over the past few years, Enceladus has enjoyed more attention than a typical moon could hope to get in its (extremely long) lifetime, and not just because we suspect it has a warm, liquid ocean sloshing just beneath its surface - theoretically the perfect place for life to arise. The best thing about Enceladus is, because of those icy plumes, we don't actually have to land on the moon and chip away at the surface to get a look - samples from the underground ocean are being sprayed right up in the atmosphere for Cassini to collect.

"If there is life in its ocean, alien microbes could be riding those geysers out into space where a passing spacecraft could grab them. No need to drill through miles of ice or dig up rocks," writes Overbye for The Times. "As Chris McKay, an astrobiologist at NASA's Ames Research Centre, said, it's as if nature had hung up a sign at Enceladus saying 'Free Samples'."

Can we get in on that?