On 24 June 2019, NASA is sending an atomic clock into space. Not just any old atomic clock, either. It's up to 50 times more accurate than the atomic clocks aboard GPS satellites, its precision only changing by one second every 10 million years.

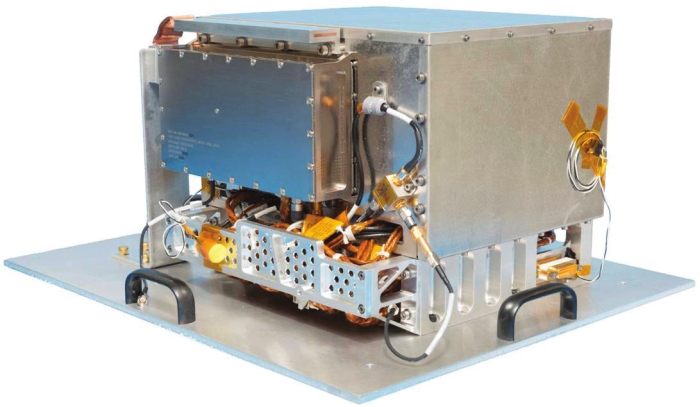

It's only the size of a toaster, yet it could revolutionise deep-space travel.

It's called the Deep Space Atomic Clock, and the next year will be crucial to its development, with NASA monitoring its performance as it orbits Earth at an altitude of 720 kilometres (447 miles) - nearly twice the distance from Earth as the International Space Station. It'll be launched aboard SpaceX's Falcon Heavy rocket.

Atomic clocks are the lynchpin of satellite navigation. GPS satellites are constantly sending light-speed radio signals transmitting the location and time they left the satellite. The receiver on Earth - your mobile phone, for instance - measures the time delay from each satellite, and converts this into spatial coordinates.

This is pretty much how spacecraft navigation works, too. Navigators here on Earth will send a signal to the spacecraft, and the spacecraft sends one back. Because the signal travels at a known speed, the time this takes allows the distance to the spacecraft to be calculated.

As you can probably imagine, the more accurate the clock, the better the location data. This is where the atomic clock comes in.

Most clocks and watches now are based on a quartz oscillator. Because quartz crystals vibrate at a regular frequency when a small electric current is applied, they can be used as the basis for keeping time. That's perfectly fine for our day-to-day timekeeping purposes, but over time these quartz oscillators lose accuracy.

After just six weeks, they can be off by as much as a millisecond, or a thousandth of a second. That may not sound like much, but if we were relying on it for space navigation, that tiny split second could mean a distance error of 300 kilometres.

Atomic clocks, on the other hand, are based on the oscillations of trapped excited atoms, which tick back and forth. And they're incredibly precise. The most accurate atomic clocks ever made wouldn't gain or lose a second for billions of years.

These are quite large objects, and would not be suitable for sending to space. The atomic clocks on satellites use caesium and rubidium atoms, and while they're much more accurate than a quartz oscillator, they still drift, and ground-based corrections need to be made twice a day from refrigerator-sized atomic clocks on Earth.

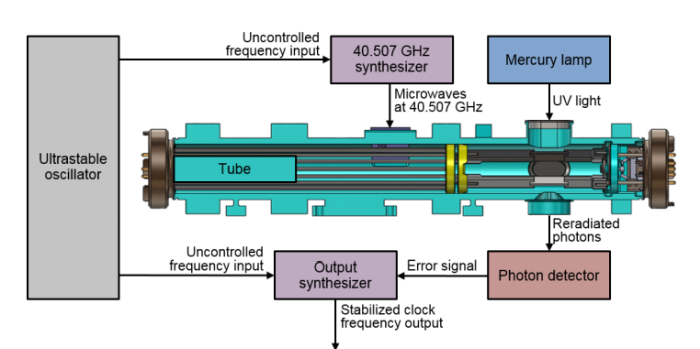

The Deep Space Atomic Clock is based on electrically charged mercury atoms, fewer than can be found in two cans of tuna, contained in an electromagnetic trap. When excited, these charged atoms, or ions, oscillate, producing optical "ticks".

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Although we've had atomic clocks since the 1950s, mercury ion atomic clocks have only been developed in the last 20 years, but they're already showing promise for finer precision.

The Deep Space Atomic Clock is, NASA says, up to 50 times more accurate than the caesium and rubidium oscillators currently in orbit. It's as stable as the ground-based atomic clocks on which their navigation is calculated.

This means that, rather than the two-way signal system currently in use, the Deep Space Atomic Clock could be used to perform tracking calculations right there on-board the spacecraft, after receipt of a signal from Earth.

A demo unit of the Deep Space Atomic Clock. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

A demo unit of the Deep Space Atomic Clock. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

That one-way tracking would mean faster, more flexible navigation, with minimal input from Earth - resulting in faster response times to unexpected events, more adroit course corrections, a spacecraft that can adapt on the fly, so to speak.

In turn, this would lighten the load on NASA's Deep Space Network of radio telescopes, allowing it to manage many space-faring vessels simultaneously as they explore the Solar System, without the need for expansion.

It could change the way we sail the stars.