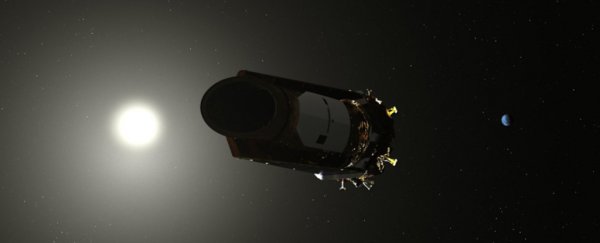

The Kepler mission is coming to an end.

The planet-hunting spacecraft that transformed our understanding of exoplanets and other solar systems is almost out of fuel.

What little fuel remains is being held in reserve to ensure that the last of its data can be sent home.

The Kepler team has placed the spacecraft in sleep mode for the time being.

They're ensuring that there's enough fuel for it to download its data via NASA's Deep Space Network. The next allotted time to do that is October 10th.

It's difficult to know exactly how much fuel is left onboard the spacecraft. If any fuel remains after its download next week, it will begin a new observing campaign. But there's a lot of uncertainty.

On Earth, or any other body with enough gravity, fuel measurement is simple. It sits on the bottom of the tank and is easily measured.

In space, an expanding air bladder inside the tank forces the fuel out of the tank. This method is effective at delivering fuel, but not for measurement.

From the Kepler FAQ:

"Kepler's fuel system uses a common approach in which the fuel tank includes an internal air bladder that is pressurized before launch to "push" the fuel into the lines. As the fuel is consumed, the bladder expands to take up more space and keep the fuel under pressure. The pressure is monitored and is used as an indicator of how much fuel remains as the expansion of the bladder results in a predictable drop in pressure. But as that remaining fuel drops and the expansion of the bladder is impeded by the walls of the tank, that predictability begins to degrade." – Kepler Fuel Status FAQ.

There are other ways to determine fuel quantity, but they're not precise.

The Kepler team looks at all of them and comes up with a consensus. And that consensus is telling them to conserve fuel and be cautious.

Kepler Discoveries

The planet-hunter was launched in 2009, and has been a great success by any measure, despite some difficulties. Its initial mission discovered 2327 confirmed exoplanets in the patch of sky it was focused on.

A star chart of the area of sky that Kepler was investigating. (NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech)

A star chart of the area of sky that Kepler was investigating. (NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech)

It suffered a serious setback in 2012, when two of the spacecraft's four reaction wheels failed. The reaction wheels allow the planet-hunter to aim very precisely, and losing two of them was a real blow.

But engineers adapted and extended the mission, although the parameters of the mission had to be changed.

This second mission was called K2, or "Second Light." K2 didn't focus solely on exoplanets. It also searched for and studied supernova explosions, star formation, and asteroids and comets.

Second Light discovered an additional 325 confirmed exoplanets. But we haven't received all of Second Light's data yet.

It's last campaign was Campaign 19, which started on August 29th. In 27 days, the spacecraft observed more than 30,000 stars and galaxies in the constellation of Aquarius.

There were dozens of known and suspected exoplanet systems, including the well-known TRAPPIST-1 system with its seven Earth-sized planets, so the exoplanet count is likely going to increase.

This painting of the Milky Way by Jon Lomberg is used as a background to show the Kepler search area. (Jon Lomberg/NASA)

This painting of the Milky Way by Jon Lomberg is used as a background to show the Kepler search area. (Jon Lomberg/NASA)

Exoplanets Before Kepler

Prior to the Kepler mission, our understanding of exoplanets was spotty. Ground-based telescopes discovered a few over the years.

The first confirmed one was in 1992, when a group of planets was discovered around Pulsar PSR B1257+12. Once NASA's planet-hunting mission was up and running, the number of confirmed exoplanets skyrocketed.

This graph shows exoplanet discoveries between 1995 and 2014, when Kepler boosted our knowledge considerably. (NASA/Kepler)

This graph shows exoplanet discoveries between 1995 and 2014, when Kepler boosted our knowledge considerably. (NASA/Kepler)

The Second Light or K2 mission discovered more than just exoplanets. In 2015, it observed three supernova explosions.

It's also discovered objects in our own Solar System, starting with the Kuiper Belt Object 2016 BP81.

Some more mission data may be coming our way on October 10th, and maybe a little more after that, fuel depending. So we don't have the final tally yet.

But it seems like the end is quickly approaching.

We won't have long to mourn the spacecraft's demise. Its successor TESS was launched in April 2018, and will spend two years monitoring 200,000 stars for exoplanets.

TESS will provide more details about exoplanet sizes and atmospheres. TESS will be better at detecting Earth-sized planets, too.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.