There are a handful of major science institutions around the world that keep track of the Earth's temperature. They all clearly show that the world's temperature has risen in the past few decades. One of those institutions is NASA.

NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Science Studies (GISS) is located in New York City. Recently, they did a complete assessment of their temperature data, called GISTEMP, or GISS surface Temperature Analysis.

The GISTEMP is one of our most direct benchmarks for tracking the Earth's temperature. It goes back over 100 years, to the 1880s.

Every year, NASA partners with the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) to update the global temperature. They use temperature data dating back to 1880 from land and sea surface measurements, combined with more modern measurements from over 6,300 weather stations research stations, and ships and weather buoys around the world.

Using all this data, the pair of organizations concluded that 2018 was the fourth-warmest year on record, and that 2016 was the warmest.

In this new study, NASA scientists analyzed the GISTEMP data to see if past predictions of rising temperatures were accurate. They needed to know that any uncertainty within their data was correctly accounted for.

The goal was to make sure that the models they use are robust enough to rely on in the future. The answer: Yes they are. Within 1/20th a degree Celsius. Kudos.

"Uncertainty is important to understand because we know that in the real world we don't know everything perfectly," said Gavin Schmidt, director of GISS and a co-author on the study.

"All science is based on knowing the limitations of the numbers that you come up with, and those uncertainties can determine whether what you're seeing is a shift or a change that is actually important."

This is scientific rigour at its finest. To a climate change denier, it may seem like ammo. But the reverse is true. NASA is determined to understand their GISTEMP data to the best of their capability, and they acknowledge, like all scientists should, any weakness in their own data and then seek to quantify it.

The NASA analysis ferreted out four sources of uncertainty, however miniscule, in the GISTEMP data.

The first is how temperature measurement changed over time, and it contributes the most uncertainty. Second was weather station coverage. You can't have a weather station at every point on Earth, so you have to interpolate the data. That interpolation is the third largest source of uncertainty, though it's contribution to uncertainty was tiny.

Lastly was how the collected data was standardized over different time periods in history.

According to Schmidt, the uncertainty value in the data is so small as to be almost insignificant: less than one tenth of one degree Celsius in recent years.

With their updated model, the team reaffirmed that 2016 was very probably the warmest year in the record, with an 86.2 percent likelihood. The next most likely candidate for warmest year on record was 2017, with a 12.5 percent probability. Spot the trend?

"We've made the uncertainty quantification more rigorous, and the conclusion to come out of the study was that we can have confidence in the accuracy of our global temperature series," said lead author Nathan Lenssen, a doctoral student at Columbia University.

"We don't have to restate any conclusions based on this analysis."

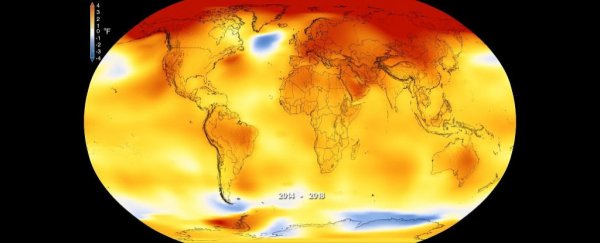

The measurements clearly show that Earth is warming in lockstep with our carbon emissions. Since 1880, the Earth's temperature has risen just over one degree Celsius, or two degrees Fahrenheit.

And the most recent years are some of the warmest on record. That makes sense, since our emissions continue to rise.

Another recent study also backed up the accuracy of GISTEMP data. NASA's Aqua Earth-observing satellite carries an instrument called Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS).

In March 2019, NASA's Joel Susskind did a study comparing GISTEMP data with AIRS data.

AIRS data is different in the way it's collected. It measures the temperature right at Earth's surface using infrared sensors. It's kind of like taking the Earth's skin temperature from space. AIRS data only goes back to 2003 when the satellite became operational, but Susskind compared it with the GISTEMP for period from 2003 to the present.

The result?

Both sets of data, though gathered independently with different methods, showed the exact same warming trend. The only difference was that AIRS data showed the northernmost latitudes are warming faster than thought.

"The Arctic is one of the places we already detected was warming the most. The AIRS data suggests that it's warming even faster than we thought," said Schmidt, who was also a co-author on the Susskind paper.

According to Schmidt, both of these studies reaffirm the accuracy of the GISTEMP data and cement its position as an accurate predictor of future temperatures.

"Each of those is a way in which you can try and provide evidence that what you're doing is real," Schmidt said. "We're testing the robustness of the method itself, the robustness of the assumptions, and of the final result against a totally independent data set."

In all cases, he said, the resulting trends are more robust than what can be accounted for by any uncertainty in the data or methods.

It's good to know our data is accurate. It's also good to know that climate scientists are honest enough to think critically and improve their own climate models and data sets.

But it's bad to know our response is still inadequate.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.