Out there in space is an unusual exoplanet name Gliese 3470 b (GJ 3470 b.) It's a strange world, kind of like a hybrid between Earth and Neptune. It has a rocky core like Earth, but is surrounded by an atmosphere made of hydrogen and helium.

That combination is unlike anything in our own Solar System.

The planet orbits a red dwarf star called Gliese 3470, in the constellation Cancer. GJ 3470 b is about 12.6 Earth masses, meaning it's roughly halfway between Earth and Neptune in mass. (Neptune is about 17 Earth masses.)

Thanks to the Kepler mission, we know that there are many exoplanets in this mass range. It's possible that up to 80 percent of planets fall in this range, though future exoplanet missions will no doubt clarify that.

Until now, astronomers haven't had a good look at the atmosphere of one of these planets, and so their formation is a bit of a mystery.

The Hubble and the Spitzer space telescopes have teamed up to take a close look at the atmosphere of GJ 3470 b, and it's the first time that astronomers have been able to identify the chemical fingerprint of the atmosphere of a planet like this.

What they found is that the planet has an almost pristine, primordial atmosphere of hydrogen and helium, without any heavier elements present. And that presents a bit of a mystery.

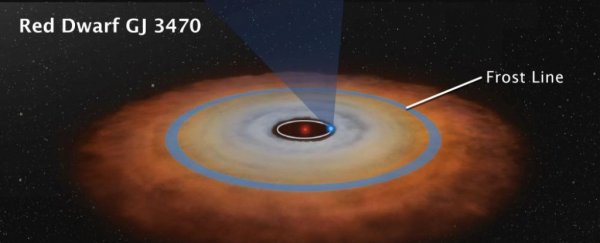

Artist's illustration shows the theoretical internal structure of GJ 3470 b. (NASA/ESA/L. Hustak/STScI)

Artist's illustration shows the theoretical internal structure of GJ 3470 b. (NASA/ESA/L. Hustak/STScI)

Half Star, Half Planet?

GJ 3470 b, with its atmosphere of hydrogen and helium, is more like a star than a planet in some ways. Our own Sun is 73 percent hydrogen, and the rest is almost all helium.

Only a tiny portion of the Sun is heavier elements like oxygen, neon, iron, and carbon. The gas giants Jupiter and Saturn are mostly hydrogen and helium, but they also contain other compounds like methane and ammonia, as well as heavier elements. Those compounds are nearly absent in GJ 3470 b.

"This is a big discovery from the planet-formation perspective. The planet orbits very close to the star and is far less massive than Jupiter – 318 times Earth's mass – but has managed to accrete the primordial hydrogen/helium atmosphere that is largely 'unpolluted' by heavier elements," said Björn Benneke of the University of Montreal in Canada, in a NASA press release.

"We don't have anything like this in the solar system, and that's what makes it striking."

The astronomers behind this work combined the multi-wavelength capabilities of both space telescopes to get a good look at GJ 3470 b's atmosphere. They did it by measuring the absorption of starlight as the exoplanet transited in front of its host star.

They also measured the loss of reflected light as the exoplanet passed behind the star. Altogether, the pair of space telescopes observed 12 transits and 20 eclipses.

Astronomers use spectroscopy to identify the chemical fingerprints of hydrogen and helium in the atmosphere, and the nature of the planet's atmosphere made this all possible.

It's mostly clear with very little haze, meaning they were able to look deeply into the atmosphere. "For the first time we have a spectroscopic signature of such a world," said Benneke.

But that spectroscopy revealed something unexpected. The astronomers thought they'd find a similar chemical composition to the planet Neptune, with heavier elements like oxygen and carbon. But instead they found an atmosphere that resembled the Sun.

"We expected an atmosphere strongly enriched in heavier elements like oxygen and carbon which are forming abundant water vapor and methane gas, similar to what we see on Neptune," said Benneke.

"Instead, we found an atmosphere that is so poor in heavy elements that its composition resembles the hydrogen/helium-rich composition of the Sun."

Piecing It Together

Now that astronomers have gotten a good handle on the exoplanet's atmosphere, thanks to the combined power of the Hubble and the Spitzer space telescopes, they can begin to understand how this oddball planet may have formed.

GJ 3470 b is in sharp contrast to other exoplanets. Astronomers think that other exoplanets, for example Hot Jupiters, form at a great distance from their Sun, and then migrate inwards.

But astronomers think that this exoplanet formed very close to its red dwarf star, close to where it's positioned today.

It likely formed as a tiny rocky object at first, enmeshed in the center of the protoplanetary disk, around the same time as the star formed. It would have gathered, or accreted, its atmosphere out of the same primordial material in the disk that the star formed from. And that would explain its hydrogen/helium atmosphere, and why it lacks heavier elements.

"We're seeing an object that was able to accrete hydrogen from the protoplanetary disk but didn't run away to become a hot Jupiter," said Benneke. "This is an intriguing regime."

What may have happened is that it was still accreting matter from the disk, but the star grew faster, and the disk dissipated. This prevented GJ 3470 b from growing larger and becoming more like the gas giants in our Solar System, with heavier elements in their atmospheres.

For now, this is where our understanding of this intriguing, oddball exoplanet stands. But once the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is up and running, it'll tell us more.

The JWST is a powerful space telescope that can see into the infrared with unprecedented sensitivity. It'll be able to probe the atmosphere of GJ 3470 b, and other exoplanets, and reveal things as yet unseen. In particular, it will observe in wavelengths that render obfuscating hazes almost transparent.

Then, our understanding of all exoplanets, not just this one, will grow in leaps and bounds.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.