NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) has only been on the job less than two months, and already it's ponying up the planet goods. The exoplanet-hunting space telescope has found two candidate planets, and there are plenty more on the horizon.

The two candidate planets are called Pi Mensae c, orbiting bright yellow dwarf star Pi Mensae, just under 60 light-years from Earth; and LHS 3844 b, orbiting red dwarf star LHS 3844, just under 49 light-years away.

TESS took its first test observations on July 25 (and managed to get some pretty great snaps of a passing comet), and its first official science observations began on August 7.

However, it was observing a large swathe of sky from the moment it opened its eyes - four optical cameras - and both discoveries are based on data from July 25 to August 22.

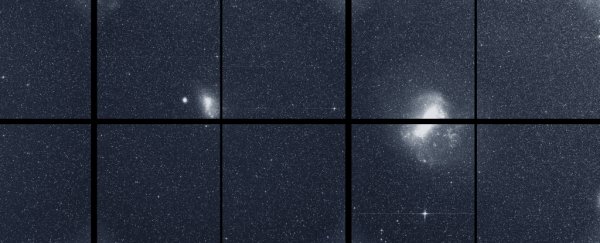

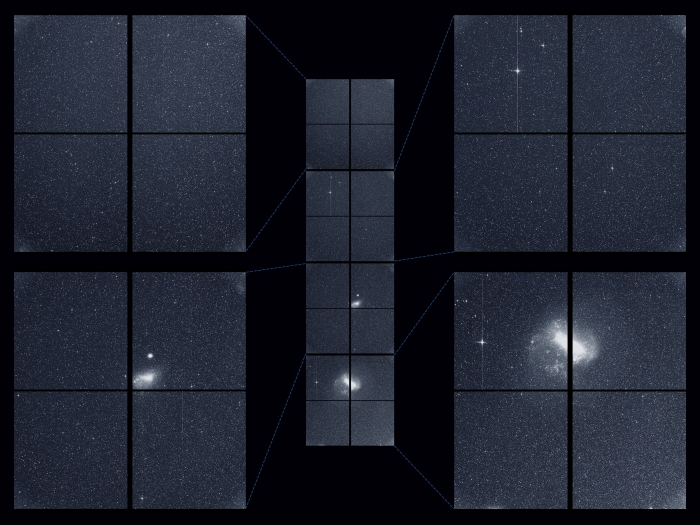

TESS's first official science observation, taken August 7. (NASA/MIT/TESS)

TESS's first official science observation, taken August 7. (NASA/MIT/TESS)

So far, they are only candidate planets, yet to be validated by the final review process. If they pass that test, they'll go down in history as TESS's first two discoveries. Here's what we know so far about them.

Both planets appear to be Earth-like and rocky, but neither is habitable according to our guidelines - both are too close to their stars for liquid water.

Pi Mensae c, the first planet announced, is a super-Earth, clocking in at just over twice the size of Earth. It's really close to Pi Mensae - it orbits the star in just 6.27 days.

A preliminary analysis indicates that the planet has a rocky iron core, and also contains a substantial proportion of lighter materials such as water, methane, hydrogen and helium - although we'll need a more detailed survey to confirm that.

It also has a sibling - it's not the first object to be found orbiting Pi Mensae. That honour goes to Pi Mensae b, an enormous planet with 10 times the mass of Jupiter discovered in 2001. It's much farther out than Pi Mensae c, on an orbit of 2,083 days.

LHS 3844 b is a little bit smaller, classified as a "hot Earth". It's just over 1.3 times the size of Earth, and on an incredibly tight orbit of just 11 hours. Since the two are so close together, it's highly likely the planet is blasted with too much stellar radiation to retain an atmosphere.

TESS does need a bit of time to collect enough data for identifying an exoplanet. Like its predecessor Kepler, it uses what is known as the transit method for detection - scanning and photographing a region of the sky multiple times, looking for changes in the brightness of stars in its field of view.

When a star dims repeatedly and regularly, that is a good indication that a planet is passing between it and TESS.

By using the amount the light dims, and Doppler spectroscopy - that is, changes in the star's light as it moves ever-so-slightly backwards and forwards due to the gravitational tug on the planet - astronomers can infer details about the planet, such as its size and mass.

Using this method, Kepler has discovered 2,652 confirmed planets to date between its first and second missions, located between 300 to 3,000 light-years away. Kepler is still operational, but barely; it's only a matter of time until it completely runs out of fuel.

TESS's search is happening a lot closer, with targets between 30 and 300 light-years away - stars brighter than those observed by Kepler. Thus, the exoplanets it identifies will be strong candidates to observe using spectroscopy, the analysis of light.

When a planet passes in front of a star, it has an effect on the light from the star, changing it based on the composition of its atmosphere (if it has one). Ground-based observatories and the James Webb Space Telescope (once it launches in 2021) will have to make those follow-up observations.

TESS, meanwhile, has a long way to go. Its mission is scheduled for a two-year period, during which it will survey 85 percent of the sky, divided into 26 sectors. NASA estimates the mission will monitor over half a million stars.

Both Pi Mensae c and LHS 3844 b were discovered in the first sector - a result that bodes well for the rest of the mission. Especially since Kepler, launched in 2009, was only planned for 3.5 years. If we're lucky, TESS will end up chugging along well after 2020.

"The discovery of a terrestrial planet around a nearby M dwarf during the first TESS observing sector suggests that the prospects for future discoveries are bright," the researchers wrote in the LHS 3844 b paper.

"It is worth remembering that 90 percent of the sky has not yet been surveyed by either TESS or Kepler."

Both papers are available on preprint resource arXiv. Pi Mensa c can be found here, and LHS 3844 b can be found here.