Methane is an organic molecule that hangs around in Earth's atmosphere and is mostly produced by living organisms, most notoriously by burping cows. Its detection on Mars, on the other hand, has been a weird mystery for planetary scientists.

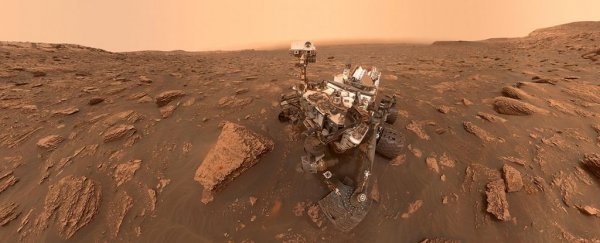

In recent years, NASA's Curiosity rover has picked up tiny traces of methane numerous times on the red planet. While these emissions might be coming from some geological process, it was possible they could indicate the presence of some sort of life form on Mars (unlikely to be cows, of course).

As you'd expect, scientists are really excited by that prospect, but the data are confusing. Higher in the atmosphere, orbiting technology from the European Space Agency (ESA) has detected no methane in any concentration.

That's strange, because even though plumes of methane would dilute into the Martian atmosphere, like a pinch of salt in an Olympic-sized swimming pool, our instruments are sensitive enough to still detect that briny hint.

"[W]hen the European team announced that it saw no methane, I was definitely shocked," says planetary scientist Chris Webster from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

So why the discrepancy? Webster and his colleagues went back to look at the data again, ruling out every little factor that might be contributing to the rover's detection of methane.

"So we looked at correlations with the pointing of the rover, the ground, the crushing of rocks, the wheel degradation - you name it," Webster explains.

"I cannot overstate the effort the team has put into looking at every little detail to make sure those measurements are correct, and they are."

As it turns out, the plumes of methane measured by Curiosity were not flukes. Instead, the discrepancy in measurements boils down to the Sun. The team found methane on the Martian surface can ebb and flow with the time of day, and the power-intensive instrument on Curiosity that detects methane mostly operates at night.

This is when the Martian atmosphere is more still, which means methane doesn't rise and dilute into the atmosphere like it does in the heat of the day. As a result, researchers think the gas sticks around near the surface of the planet at night, and during the day, the methane is diluted such that ESA's orbiting instrument (which needs sunlight to work) can't detect it at a distance.

To confirm their prediction, the research team collected high-precision measurements of Martian methane over the course of two days, the first time Curiosity has done so in daylight. They also took measurements during the intervening night.

As expected, the seeping methane sat near the surface of the planet at night and dissolved into the atmosphere in the day.

"John [E. Moores, another member of Curiosity's science team] predicted that methane should effectively go down to zero during the day, and our two daytime measurements confirmed that," explains planetary scientist Paul Mahaffy from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

"So that's one way of putting to bed this big discrepancy."

It's still unclear, however, why methane doesn't appear to be building up in the Martian atmosphere over time - according to the researchers, it should last for at least 300 years before degrading in the radiation streaming from the Sun.

Since it's unlikely for the Gale crater to be the only source of this planetary micro-seepage of methane (because Gale crater just isn't that special from a geological perspective), they think something must be destroying or sequestering all that methane before it can gather in the atmosphere.

The team is now testing whether dust or an abundance of oxygen could play a role in that.

Part of the mystery might be solved, but now we have more questions. Curiosity is living up to its name.

The study was published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.