The rover attempted to collect its first core last week, but its tube came out empty. There was a finger-size hole in the rock where the sample should have come out, along with a pile of "cuttings" from the drill around the hole. But there was no sample anywhere in sight.

After analyzing data and photos from the rover for several days, NASA's Perseverance team determined that the rock most likely crumbled into powder or "small fragments".

"It appears that the rock was not robust enough to produce a core," Louise Jandura, chief engineer for the sampling system, said in a NASA blog post on Wednesday. "The material from the desired core is likely either in the bottom of the hole, in the cuttings pile, or some combination of both."

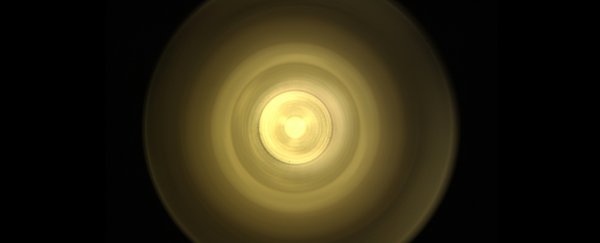

The hole Perseverance drilled into a Mars rock, 7 August 2021. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The hole Perseverance drilled into a Mars rock, 7 August 2021. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

So now the team is planning to send Perseverance to a different spot, a sandy area called Seitah, where they'll choose a different kind of rock to sample that should be stronger. That ancient lake sediment should more closely resemble the rocks the team used to test Perseverance's tools on Earth. NASA aims to try coring a new rock next month.

"The hardware performed as commanded but the rock did not cooperate this time. It reminds me yet again of the nature of exploration," Jandura wrote in the blog. "A specific result is never guaranteed no matter how much you prepare."

The failed first attempt wasn't a technical failure; Perseverance appears to have done everything it was supposed to. It used an abrasion tool to clear away dust and surface coatings from its target: a rock in an ancient Mars lake bed that could have once held alien life.

Then the rover extended its 7-foot (2 metre)-long arm, which has a sample-collection tool on the end. This tool uses a percussive drill to push a hollow coring bit into the rock, and that drill went in as planned. The tube just came up empty.

Perseverance sample-collection arm. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU)

Perseverance sample-collection arm. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU)

Still, that tube is one of 43 that Perseverance is carrying. They're the cornerstone of the rover's main mission on Mars – to explore a region called Jezero Crater and gather samples

NASA has already spent nine years and about US$2 billion in its quest to drill and store samples of Martian rocks. In about a decade, it plans to send another mission to Mars to retrieve the samples and bring them back to Earth. Then scientists can investigate whether microbial life may have lived in the lake that once filled Jezero Crater.

In other words, a significant amount of planning and money is riding on these samples. That's in part why the last few days have been "a rollercoaster of emotions," according to Jandura.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: