Compared with the gregarious nature of modern humans, Neanderthal communities appear to have been surprisingly insular, according to past research, keeping to themselves more often than not.

One group appears to have taken reclusivity to an extreme. A new study on genetic material lifted from the molars of a specimen named Thorin has found his ancestors hadn't mixed with their neighbors for millennia.

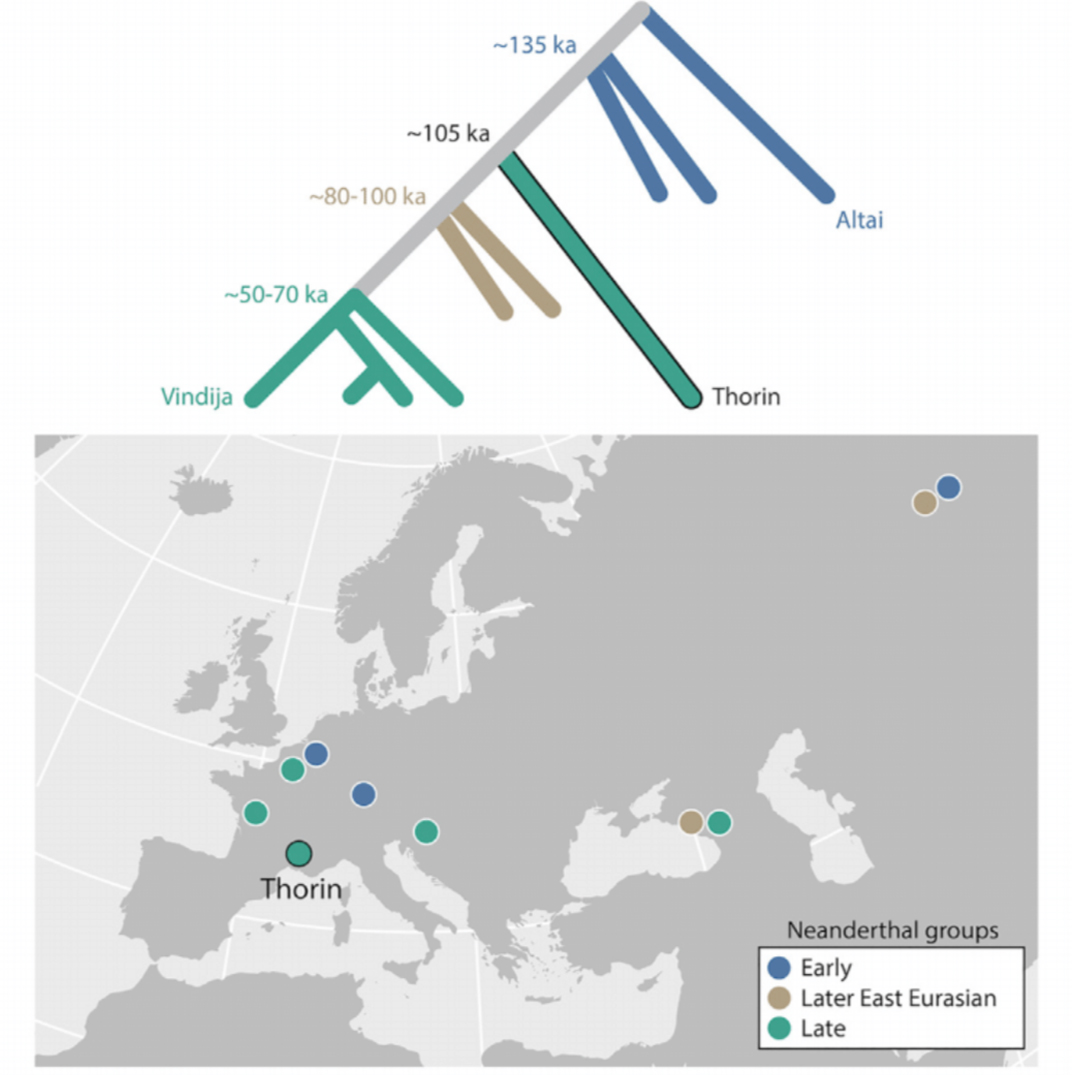

"The Thorin population spent 50,000 years without exchanging genes with other Neanderthal populations," explains Paul Sabatier University archaeologist Ludovic Slimak.

Coincidentally, this group of Homo neanderthalensis' isolation coincides with our own ancestor's forays into Europe.

"Thorin corresponds to the phases of Neanderthal reoccupation of Grotte Mandrin after the earliest modern human incursions in the continent," Slimak and colleagues explain in their paper.

Discovered in 1979 in France's Rhone Valley caves, Thorin's 100,000 year old remains represent the most complete Neanderthal found in France, dating to the last millennia of their existence in this region.

Around this time Neanderthal populations in Spain were being overturned, with changes in genes indicating a replacement by new populations of Neanderthal as drastic climate warming changed environmental conditions after the previous ice age and drove other lineages to expand into new territory.

Hot on their heels were Homo sapiens.

"These genetic differences may signify a major process of population replacement following or related to the expansion of anatomically modern humans through Europe," Slimak and colleagues write.

While many of us carry some Neanderthal DNA, we have yet to find Neanderthals with recent human DNA.

Thorin was no exception. The closest match to Thorin's genetics was another Neanderthal found in Gibraltar, Spain. And even then, the last time Thorin's ancestors mated with the other known groups of Neanderthals was 50,000 years earlier.

"This means there was an unknown Mediterranean population of Neanderthals whose population spanned from the most western tip of Europe all the way to the Rhône Valley in France," says Slimak.

But the genetic material from fossils representing Mediterranean populations is incomplete, making any claims on this mysterious group hard to confirm.

Regardless, the isolation of Thorin's people raises questions on how his species as a whole ultimately met its end about 40,000 years ago.

Genetic seclusion aside, there is also cultural archeological evidence that this Neanderthal group was extremely insular. This may be a clue to how our extinct cousins faded from existence despite sharing many of the traits that helped us excel in challenging environments, from their technological skills to their aptitude for creativity.

In contrast, the wave of humans that washed through Asia as Neanderthals disappeared seemed to maintain cultural connections across Europe, suggesting there was resilience in fostering strong ties.

"It's always a good thing for a population to be in contact with other populations," says Vimala. "When you are isolated for a long time, you limit the genetic variation that you have, which means you have less ability to adapt to changing climates and pathogens, and it also limits you socially because you're not sharing knowledge or evolving as a population."

Rather than a dramatic end full of conflict between two types of human, the decline of Neanderthals may have been a long and complex process brought on by their own desire to withdraw into themselves.

This research was published in Cell Genomics.