Tens of thousands of years before Swiss inventor Karl Elsener attached a corkscrew to a pocketknife, Neanderthals had their own multipurpose tools: hand axes.

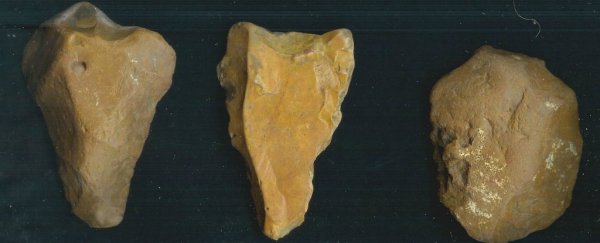

These four- or five-inch (10 -13 centimetre) stones were cut into large teardrop shapes, with wide bases that tapered to twin cutting edges. Neanderthals used hand axes to chop and carve wood, butcher meat, scrape hides and sharpen other tools.

And, possibly, they started fires. So suggests a study of these stone-age Swiss army knives published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports.

In experimental trials, archaeologist Andrew Sorensen, a researcher at Leiden University in the Netherlands, struck pyrite against hand axes to set tinder ablaze.

"It makes total sense to me that, beside other possible uses, they also served as lighter when struck with a little block of pyrite," said paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, who was not involved with this research.

Pyrite, or fool's gold, makes sparks when struck by flint. Repeatedly hitting the axes with pyrite also leaves distinct scratches on the stone tools.

That wear and tear, Sorensen and his colleagues reported, mirrored the marks found on hand axes at archaeological sites in southwestern France.

"When you zoom in at the micro scale, you see this mineral polish and also a series of scratches in the surface," Sorensen said. The marks run in parallel and are clustered together, an indication, he said, that the Neanderthals deliberately made them.

Twenty-six surfaces on 20 hand axes (some of the axes had marks on both sides) collected from the French Neanderthal sites contained "either probable or possible" scratches that indicated fire starting, the study authors wrote.

It was possible that certain Neanderthal groups "might have discovered that striking flint could light a fire," said University of Toronto anthropologist Michael Chazan, who was not a part of this research.

But the study, which Chazan described as "thorough," cannot prove that Neanderthals actually used flint to light fires - it could only put it in the realm of possibility.

"We should never underestimate the ingenuity of Neanderthals," Chazan said, "but that does not mean they were just like modern humans."

Among researchers who study Neanderthals, fire is "kind of a hot topic," said Dennis Sandgathe, an expert in Paleolithic stone technology at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia.

Most experts, including Sandgathe and Sorensen, agree that these archaic humans used fire to their advantage. The current state of Neanderthal research, however, has not convinced Sandgathe that they learned how to spark fire.

He did not mean to suggest that Neanderthals are less intelligent for this deficit:

"It's like the wheel," he said. "There are some cultures that used the wheel and some cultures that didn't."

Historians and scientists have always viewed fire as significant. The Promethean discovery was one of the biggest innovations in prehistory, if not the singularly most important one.

But only in the last 10 to 15 years have researchers looked in earnest for fires at Neanderthal sites in Western Europe and the Middle East.

Like Everest mountaineers, Neanderthals were profligate litterers. And their trash, likewise, endures. "Pretty much every stone tool that's ever been made in the prehistory of humans is still in existence," Sandgathe said.

Burn marks preserved on discarded hand axes and flints reveal that Neanderthals had fire. Perhaps Neanderthals cooked their meat to keep it from spoiling in warm months.

Perhaps they hardened their wood tools in flames. Perhaps they even used fire to create the first glue, by burning birch to produce tar.

Sandgathe hypothesizes that Neanderthals harnessed natural wildfires, collecting forest embers to light their flames. He offered several critiques of the new study.

Matching experimental scratches to historical specimens, a common technique called use-wear analysis, is "always ambiguous," he said.

Sorensen, who sees flaws in the wildfire argument, acknowledged the ambiguities in use-wear research. "We always explain that it's an interpretation," he said. Neanderthals possibly used the hand axes for a different task, with a different mineral, and that behavior caused the scratches.

But Sorensen said no other researcher has put forth a better explanation. "Until that happens," he said, "this really just seems like the best fit for these traces."

Sandgathe pointed to fire-free periods in the archaeological record. For long durations of time, signs of Neanderthal fires vanish. Those periods appear to be in sync with advancing glaciers and cooler global temperatures.

Sandgathe suggests that a lack of those vital wildfire embers during ice ages could explain the absence of Neanderthal fires.

In Sorensen's interpretation, a lack of fuel is the culprit. Colder periods probably shrank the amount of available wood. If the Neanderthals had to keep natural-born fires fed, they would have had to spend much more time collecting wood.

But if they had the ability to make fire, he said, "they could be much more economical with their fuel."

Hublin agreed. "During cold episodes, in environments where fuel was not easily available," he said, "the cost of collecting wood might have been higher than the benefits of having a fire."

This observation also suggests Neanderthals prospered in the cold "without fire and without cooking," he said, which modern human hunter-gatherers could not do.

In Sorensen's view, ice age Neanderthals created fires only when they were truly hankering for a blaze. "Short-term, smaller fires as-needed will leave much weaker signals archaeologically and create the illusion that they weren't using it as often," he said.

Sandgathe noted a lack of pyrite at Neanderthal sites. But pyrite decay, a chemical reaction between the mineral and humid air that "completely eats away" pyrite in a matter of years, could explain its absence, Sorensen said.

Sorensen plans to trace this technology forward in time, to see if early modern humans showed signs of strike-a-light flints. It could, possibly, be a technology we learned from Neanderthals, he speculated.

Or maybe our ancestors made sparks by rubbing two pieces of wood together. Which is nice for starting fires but a bit of a loss for archaeologists: If you're using two pieces of wood to make fires, after all, where better to discard the sticks than into the fire?

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.