A dwarf planet thought to have some ice mixed in with its dirty surface may have a lot more cool than we ever expected.

Ceres – the largest body in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter – could have a crust consisting of more than 90 percent water ice. If this is the case, the heavily cratered and scarred object could have a lot to teach us about ocean worlds, and what they can look like when they freeze over completely.

"We think that there's lots of water-ice near Ceres's surface, and that it gets gradually less icy as you go deeper and deeper," says planetary geophysicist Mike Sori of Purdue University in the US.

First discovered in 1801, Ceres is sometimes referred to as an asteroid because of where it hangs out in the Solar System; but it's big and spherical enough to be classified as a dwarf planet, just under half the size of Pluto.

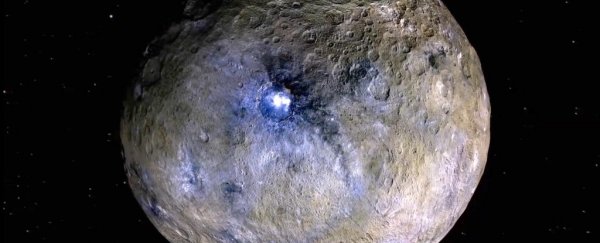

It's also quite an interesting oddball. It's the only dwarf planet closer to the Sun than Neptune, and speckled with bright spots that may be evidence of ice volcanoes on its surface.

So it's likely that there's least some water there, but how much? Previous estimates, based on cratering of the surface, placed the quantity at no more than 30 percent.

That's because, if the surface was water ice, scientists thought that it would gradually deform over time, and become smoother and shallower. When NASA's Dawn spacecraft arrived at Ceres in 2015, it found well-defined craters that were inconsistent with what researchers had expected to see if Ceres was icy, so they made their estimates accordingly.

"People used to think that if Ceres was very icy, the craters would deform quickly over time, like glaciers flowing on Earth, or like gooey flowing honey. However, we've shown through our simulations that ice can be much stronger in conditions on Ceres than previously predicted if you mix in just a little bit of solid rock," says Sori.

Using data from the Dawn mission and computer simulations of an icy world, a team led by planetary scientist Ian Pamerleau of Purdue University sought to investigate whether this assumption was correct.

And they found that it would only take a little bit of dirt mixed into the ice to give it enough structural integrity to maintain crisp craters.

"Even solids will flow over long timescales, and ice flows more readily than rock. Craters have deep bowls which produce high stresses that then relax to a lower stress state, resulting in a shallower bowl via solid state flow," Pamerleau explains.

"Our computer simulations account for a new way that ice can flow with only a little bit of non-ice impurities mixed in, which would allow for a very ice-rich crust to barely flow even over billions of years. Therefore, we could get an ice-rich Ceres that still matches the observed lack of crater relaxation. We tested different crustal structures in these simulations and found that a gradational crust with a high ice content near the surface that grades down to lower ice with depth was the best way to limit relaxation of Cerean craters."

As much as over 90 percent of the dwarf planet's crust could be water ice, giving some insight, the researchers believe, into ice-covered ocean worlds. There are quite a few of these in the Solar System, including Jovian moons Europa and possibly Ganymede, Kronian moons Enceladus and Mimas, and likely Uranian moons Miranda and Ariel.

These moons have a thick shell of ice, under which an ocean of liquid water is thought to be maintained by the heat generated by the gravitational interaction between moon and planet.

Ceres doesn't orbit a planet, which means there's no tidal activity to keep its insides warm. Any ocean that once sloshed there, the researchers say, would be completely frozen over.

"Our interpretation of all this is that Ceres used to be an 'ocean world' like Europa, but with a dirty, muddy ocean," Sori says. "As that muddy ocean froze over time, it created an icy crust with a little bit of rocky material trapped in it."

If this is the case, it means ocean worlds could look a lot different from what we might expect. In addition, NASA has sent a spacecraft to Ceres before. It could do so again – and the dwarf planet's possible frozen ocean world status makes it a very intriguing research target.

"To me the exciting part of all this, if we're right, is that we have a frozen ocean world pretty close to Earth. Ceres may be a valuable point of comparison for the ocean-hosting icy moons of the outer Solar System, like Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's moon Enceladus," Sori says.

"Ceres, we think, is therefore the most accessible icy world in the Universe. That makes it a great target for future spacecraft missions."

The research has been published in Nature Astronomy.