After not seeing the light of day for at least 30 years, a unique collection of letters by famous mathematician Alan Turing has been found in a storage space at his old university.

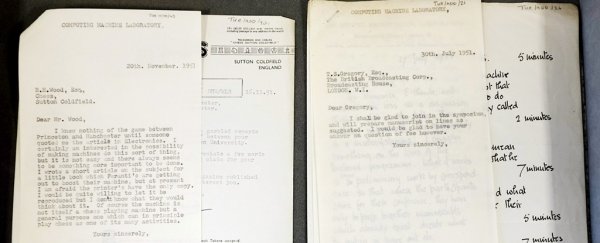

Wrapped in a plain paper folder and tucked at the back of an old filing cabinet, the 148 never-before seen documents include a letter from the UK's intelligence services, and another letter in which Turing remarks "I detest America."

Alan Turing was one of the pioneers of modern computer science, and a machine he built during the World War II enabled the decryption of Germany's Enigma code, eventually shortening the war.

In 1949 he became deputy director of the computing lab at the University of Manchester, and earlier this year the university staff accidentally stumbled upon a whole heap of Turing's correspondence while cleaning out a storage room.

"When I first found it I initially thought, 'that can't be what I think it is', but a quick inspection showed it was," says computer engineer Jim Miles from the university's School of Computer Science.

"I was astonished such a thing had remained hidden out of sight for so long. No one who now works in the School or at the university knew they even existed."

The university's archivists immediately set to work to sort through these documents, cataloguing and storing them for posterity, and have now published the entire archive online for readers to peruse.

The file contained both correspondence and other materials dating from early 1949 up to Turing's untimely death in June 1954. It was mostly 'work stuff' you would expect a busy academic to have piling up on his desk.

Unfortunately we can't expect to learn much about his wartime work on the code-breaking machine, since the Enigma efforts were still top secret at the time, although there is one letter from the then-director of Britain's secret GCHQ organisation.

These are also not the sort of letters you can expect to reveal much in the way of Turing's private life, including the widely-publicised 1952 conviction of indecency because of his relationship with another man.

"There is very little in the way of personal correspondence, and no letters from Turing family members," says archivist James Peters who sorted the documents.

"But this still gives us an extremely interesting account and insight into his working practices and academic life whilst he was at the University of Manchester."

There are letters from fellow academics and students, commenting on Turing's work, discussing computing and mathematics problems, and even requesting advice. There are also numerous invitations to give guest lectures and attend conferences.

To one such invitation by physicist Donald Mackay from King's College London, who inquired whether Turing would be going to a 1953 cybernetics conference in the US, Turing simply replied that the meeting held appeal but he did not want to travel there.

"I would not like the journey, and I detest America," he wrote.

Overall, historians are thrilled to have dug up this unique collection, entirely by accident. Despite his massive contribution to the fields of mathematics and computation, there is extremely scarce archival material on Turing's life, especially the later years.

"As there is so little actual archive on this period of his life, this is a very important find in that context," says Peters.

"There really is nothing else like it."

You can browse this archival treasure trove by visiting the university's archive here.