Around 7,000 years ago - all the way back in the Neolithic - something really peculiar happened to human genetic diversity. Over the next 2,000 years, and seen across Africa, Europe and Asia, the genetic diversity of the Y chromosome collapsed, becoming as though there was only one man for every 17 women.

Now, through computer modelling, researchers believe they have found the cause of this mysterious phenomenon: fighting between patrilineal clans.

Drops in genetic diversity among humans are not unheard of, inferred based on genetic patterns in modern humans. But these usually affect entire populations, probably as the result of a disaster or other event that shrinks the population and therefore the gene pool.

But the Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck, as it is known, has been something of a puzzle since its discovery in 2015. This is because it was only observed on the genes on the Y chromosome that get passed down from father to son - which means it only affected men.

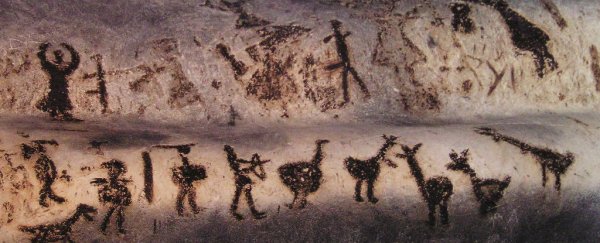

This points to a social, rather than an environmental, cause, and given the social restructures between 12,000 and 8,000 years ago as humans shifted to more agrarian cultures with patrilineal structures, this may have had something to do with it.

In fact, a drop in genetic diversity doesn't mean that there was necessarily a drop in population. The number of men could very well have stayed the same, while the pool of men who produced offspring declined.

This was one of the scenarios proposed by the scientists who penned the 2015 paper.

"Instead of 'survival of the fittest' in a biological sense, the accumulation of wealth and power may have increased the reproductive success of a limited number of 'socially fit' males and their sons," computational biologist Melissa Wilson Sayres of Arizona State University explained at the time.

Tian Chen Zeng, a sociologist at Stanford, has now built on this hypothesis. He and colleagues point out that, within a clan, women could have married into new clans, while men stayed with their own clans their entire lives. This would mean that, within the clan, Y chromosome variation is limited.

However, it doesn't explain why there was so little variation between different clans. However, if skirmishes wiped out entire clans, that could have wiped out many male lineages - diminishing Y chromosome variance.

Computer modelling have verified the plausibility of this scenario. Simulations showed that wars between patrilineal clans, where women moved around but men stayed in their own clans, had a drastic effect on Y chromosome diversity over time.

It also showed that a social structure that allowed both men and women to move between clans would not have this effect on Y chromosome diversity, even if there was conflict between them.

This means that warring patrilineal clans are the most likely explanation, the researchers said.

"Our proposal is supported by findings in archaeogenetics and anthropological theory," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"First, our proposal involves an episode in human prehistory when patrilineal descent groups were the socially salient and major unit of intergroup competition, bracketed on either side by periods when this was not the case,"

This hypothesis is also supported by a finding in the European DNA samples - shallow coalescence of the Y chromosome, a feature that indicates high levels of relatedness between males.

"Groups of males in European post-Neolithic agropastoralist cultures appear to descend patrilineally from a comparatively smaller number of progenitors when compared to hunter gatherers, and this pattern is especially pronounced among pastoralists," they explained.

"Our hypothesis would predict that post Neolithic societies, despite their larger population size, have difficulty retaining ancestral diversity of Y-chromosomes due to mechanisms that accelerate their genetic drift, which is certainly in accord with the data."

Interestingly, there were variations in the intensity of the bottleneck. It is less pronounced in East and Southeast Asian populations than in European, West or South Asian populations. This could be because pastoral cultures were much more important in the latter regions.

The team are excited to apply their methodology, which combines sociology, biology and mathematics, to other cultures, to observe how kinship links and genetic variation between cultural groups correlates with political history.

"An investigation into the patterns of uniparental variation among, for example, the Betsileo highlanders of Madagascar, who may have undergone an entry and an exit from the 'bottleneck period' very recently, could reveal phenomena relevant to such history," the researchers wrote.

"Cultural changes in political and social organisation - phenomena that are unique to human beings - may extend their reach into patterns of genetic variation in ways yet to be discovered."

The team's research has been published in the journal Nature Communications.