As a rule, your brain's activity doesn't influence the physiological development of your sex cells. In simpler terms: What you 'think' can't be inherited. But now it looks like we may need to rethink this rule for at least one species.

The activity of nematode neurons has been shown to influence the foraging behaviour of the next generation of worms, and it could be caused by a novel inheritance pathway.

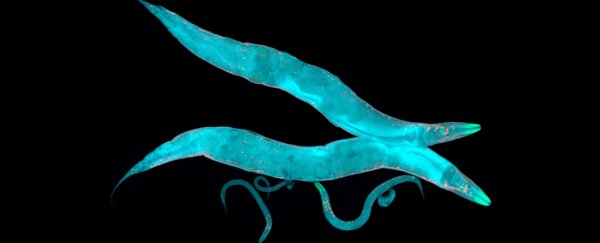

A team of scientists from Tel Aviv University in Israel describes how free-floating strands of RNA generated inside roundworm (Caenorhabditis elegans) neurons affect the way subsequent generations sniff out their meals.

"We found that small RNAs convey information derived from neurons to the progeny and influence a variety of physiological processes, including the food-seeking behaviour of the progeny," says biologist Oded Rechavi.

Rechavi's team confesses their main goal is to challenge scientific dogmas, especially those on inheritance. This is certainly a big challenge to a long-established assumption in biology, so it deserves heavy scrutiny before we accept it.

With that in mind, the discovery is potentially huge: it could describe an entirely new mechanism by which one generation affects the physical state of the next.

For most of last century, we figured there were just two ways information might be passed from a parent to a child – genetically, through the coding of their DNA; and culturally, by behaving in ways that indirectly affect their offspring's development.

Over recent decades, biologists have come to learn more about subtle editorial tweaks that can change how genes are read by applying a form of chemical lock.

Since these 'epigenetic' processes can be influenced by the environment, it's now seen as another way events that take place in the lives of one generation can affect the development of not only children, but potentially multiple generations.

Parental behaviours might produce epigenetic changes through affection or extreme lack thereof, but any immediate connection between the chemistry of their neurons to the genes inside their stem cells is thought to be against the rules.

"It was long thought that brain activity could have absolutely no impact on the fate of the progeny," says Rechavi.

"The Weismann Barrier, also known as the Second Law of Biology, states that inherited information in the germline is supposed to be isolated from environmental influences."

Several years ago, US researchers showed mobile segments of double-stranded RNA generated by nematode neurons could end up in their germ cells, and even silence some of the cell's genes.

While astonishing, the study fell short of demonstrating any significant changes in the offspring's functions.

Rechavi and his team have now demonstrated that inheriting these neuronal RNA fragments can result in differences in learning and behaviour not just in the next generation, but for several generations down the line.

They removed a key RNA binding protein gene from transgenic strains of C. elegans to demonstrate the protein's role in managing the levels of RNA fragments both in nerves and germ cells.

Presence of that binding protein had a big difference in whether offspring detected chemicals in their environment at different temperatures, implying the RNA generated by their parent's neurons affects how their own nervous system functions.

The exact changes to their nervous system responsible for the reduced ability to sniff their environment aren't known, so there's still plenty of work to be done.

But it's an exciting step in demonstrating how RNA made by the neurons of a parent can slip into their offspring's cells to promote a rather important function.

Half a century ago, a controversial experiment by the University of Michigan psychologist James V. McConnell concluded memories could be passed through the consumption of RNA in cannibalistic flatworms.

The experiment is today regarded as a quirky episode in the history of science, often reported as pseudoscience.

While McConnell's cannibals have become folklore, recent experiments still hint at some kind of interaction between mobile RNA fragments and neural activity. One such study just last year claimed to use RNA to 'transfer' the experience of a shock from one snail to the next.

We need to be careful not to translate any of this research into human experiences. There's a world of difference in how we imagine memories in our brains compared with conditioned responses in other organisms.

But if this research pans out, the one-way street of genetic inheritance is far more complicated than we thought.

"Through this route, parents could potentially transmit information that would be beneficial to the progeny in the context of natural selection," says biologist and study co-author Itai A. Toker.

"It could therefore potentially influence an organism's evolutionary course."

This research was published in Cell.