Like all stars, our Sun is powered by the fusion of hydrogen into heavier elements. Nuclear fusion is not only what makes stars shine, it is also a primary source of the chemical elements that make the world around us.

Much of our understanding of stellar fusion comes from theoretical models of atomic nuclei, but for our closest star, we also have another source: neutrinos created in the Sun's core.

Whenever atomic nuclei undergo fusion, they produce not only high energy gamma rays but also neutrinos. While the gamma rays heat the Sun's interior over thousands of years, neutrinos zip out of the Sun at nearly the speed of light.

Solar neutrinos were first detected in the 1960s, but it was difficult to learn much about them other than the fact that they were emitted from the Sun. This proved that nuclear fusion occurs in the Sun, but not the type of fusion.

According to theory, the dominant form of fusion in the Sun should be the fusion of protons that produces helium from hydrogen. Known as the pp-chain, it is the easiest reaction for stars to create.

For larger stars with hotter and more dense cores, a more powerful reaction known as the CNO-cycle is the dominant source of energy. This reaction uses hydrogen in a cycle of reactions with carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen to produce helium.

The CNO cycle is part of the reason why these three elements are among the most abundant in the Universe (other than hydrogen and helium).

The CNO cycle kicks in at higher temperatures. (RJ Hall)

The CNO cycle kicks in at higher temperatures. (RJ Hall)

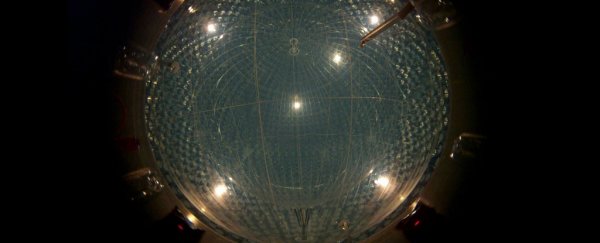

In the past decade neutrino detectors have become much for efficient. Modern detectors are also able to detect not just the energy of a neutrino, but also its flavor.

We now know that the solar neutrinos detected from early experiments come not from the common pp-chain neutrinos, but from secondary reactions such as boron decay, which create higher energy neutrinos that are easier to detect.

Then in 2014, a team detected low-energy neutrinos directly produced by the pp-chain. Their observations confirmed that 99 percent of the Sun's energy is generated by proton-proton fusion.

The energy levels of various solar neutrinos. (HERON/Brown University)

The energy levels of various solar neutrinos. (HERON/Brown University)

While the pp-chain dominates fusion in the Sun, our star is large enough that the CNO cycle should occur at a low level. It should be what accounts for that extra 1 percent of the energy produced by the Sun.

But because CNO neutrinos are rare, they are difficult to detect. But recently a team successfully observed them.

One of the biggest challenges with detecting CNO neutrinos is that their signal tends to be buried within terrestrial neutrino noise. Nuclear fusion doesn't occur naturally on Earth, but low levels of radioactive decay from terrestrial rocks can trigger events in a neutrino detector that are similar to CNO neutrino detections.

So the team created a sophisticated analysis process that filters the neutrino signal from false positives. Their study confirms that CNO fusion occurs within our Sun at predicted levels.

The CNO cycle plays a minor role in our Sun, but it is central to the life and evolution of more massive stars.

This work should help us understand the cycle of large stars, and could help us better understand the origin of the heavier elements that make life on Earth possible.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.