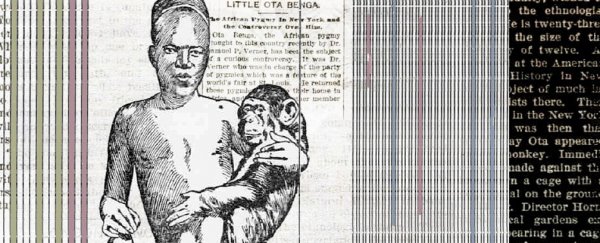

In a stunning account of relatively recent US history, a new book lays bare the conditions surrounding the captivity of Ota Benga, a Congolese man who was controversially exhibited for 20 days at the Bronx Zoo in New York during 1906.

Written by Pamela Newkirk, a journalist and researcher with New York University, the book aims to set the record straight on any suggestions Benga was a willing party who voluntarily agreed to be caged for zoogoers' amusement, and serves as a reminder of just how far 'scientific' values have come in a little over a century.

Benga was brought to the Bronx Zoo (aka the New York Zoological Gardens) by Samuel Verner, an explorer who discovered Benga in Africa and brought him back to the United States. Once at the Zoo, Benga was displayed in a cage at a 'Primate House' exhibit. The floor of his cage was scattered with bones to suggest its inhabitant was a fearsome cannibal. Unlike other exhibitions of humans that occurred in this period of history, Benga was not housed with others of his own kind, but rather made to share his cage with another 'primate': an orangutan called Dohong.

Benga's inhuman treatment was controversial even at the time, but that didn't stop him becoming a huge hit for the Zoo: attendance doubled to nearly a quarter of a million visitors in the month he was displayed, almost twice the count of the previous September.

Werner's descendants and the Bronx Zoo itself have always maintained that Benga was somehow an accomplice to his own captivity, either by being a friend of Werner's or acting as a paid employee of the zoo. However, sifting through historical archives, Newkirk found evidence of a very different story.

"It was so stunning and so clear that Ota Benga was being held against his wishes and that there was an utter disregard for his life, his will, his being," says Newkirk in a statement.

Her book makes clear how racism was entrenched not only in society but in the scientific institutions of the time:

Case in point – three of the men who orchestrated Benga's display were respected scientists with considerable social and political clout: One of the Bronx Zoo's cofounders, Madison Grant, was author of the influential book The Passing of the Great Race, which argued for anti-miscegenation laws and sterilisation of "inferior" races – and carried a ringing endorsement from Theodore Roosevelt on its book jacket. Another cofounder, Henry Fairfield Osborn, was the son of railroad magnate William Henry Osborn, taught at Columbia, served as a palaeontologist for the U.S. Geological Survey, and ultimately became president of the American Museum of Natural History. The zoo's first director, top zoologist William Temple Hornaday, had previously served as the first superintendent of the National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C.

To Newkirk, the most disappointing thing is her claim that the Bronx Zoo still doesn't truthfully acknowledge what occurred, maintaining as recently as 1974 in a publication that Benga was an employee, not a specimen.

"The shame of a cover-up means that you're never going to acknowledge you made a mistake," she says. "And we all make mistakes – but for someone to willingly doctor history is kind of stunning. Why not own up to it? Why not say, 'God, we're better now.'"

We love science and all the incredible things that it's done for the world, but it's also important to look back and acknowledge that in the past things have been done in the name of science that are totally incompatible with the values we have as a society today. The hope is, by doing so, we can help to avoid these sorts of injustices in the future.