Up until a few years ago, it was widely accepted that the neurons you're born with are pretty much all you get. Then a handful of studies made us think we had it all wrong and neurogenesis continued throughout our adult years.

Now a study just published in Nature has found that our ability to grow new neurons does indeed slow to a crawl in our youth - so maybe we need to look after our brain cells more than we thought.

Let's just get one thing out of the way: neuroscience is hard. Really hard. Discovering new brain cells isn't as simple as digging out a chunk of grey matter and looking at it under a microscope.

Over the past few years, a number of studies have come out enthusiastically overturning the old adage that our brains stop growing new cells long before we hit adulthood.

To get around many of the practical and ethical challenges that come with studying human nervous systems, a number of the researchers based their conclusions on signs of new growth in rodents.

While these kinds of methods come with the usual caveat 'mouse brains aren't human brains', the excitement of challenging the status quo can often overshadow the need for caution.

This latest study led by researchers from the University of California, San Francisco, identified the maturity of a type of brain cell taken from a mix of 59 deceased and living patients, and used this to estimate when we stop growing new neurons.

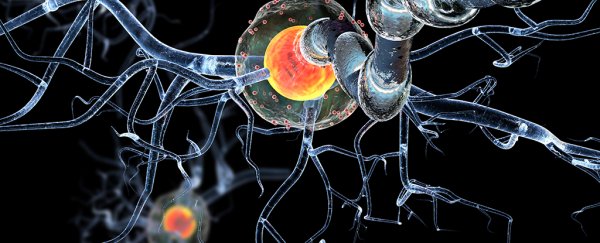

Specifically, the team focussed on cells taken from the dentate gyrus, an area of the hippocampus which previous research had found could be growing as many as 700 new brain cells every day.

The specimens were taken from individuals ranging from a 14-week-old foetus to a 77-year-old male, providing the team with a spectrum of neurological development.

What they found showed a timeline of development that slowed after birth and stopped in adolescence.

Samples taken from the 14-week-old foetus contained precursor cells, proliferating neurons, and mature tissue migrating towards the dentate gyrus.

By age one, it seemed as if new nerve growth in this area was slowing, with far fewer precursor cells.

Beyond age 13 there were no proliferating neurons to be seen in the hippocampus, contradicting previous research.

There are a couple of take-home messages from this study.

Firstly, we might have been right all along – human brains really don't generate new neurons into adulthood.

Secondly, taking prior studies on mice into account, it seems as if human brains are more unique than we ever suspected.

This leaves us with a fascinating question – why do some animals grow new brain cells when we don't?

Answering this question could point the way to novel treatments for degenerative brain conditions, if not show us why they arise in the first place.

It's easy to be cynical and wonder why science simply can't make up its mind, but as frustrating as it seems, this is the methodology of science in action.

No doubt this research is far from the final word on the matter, as the back-and-forth continues to add ever more detail to what is probably the most complicated organ in the human body.

This research was published in Nature.