Giraffe ancestors had shorter necks. Why that changed so drastically over their evolution has stirred a surprising amount of debate since the time of Charles Darwin.

While a recent theory suggests regulating body temperature may have played a role, the main giraffe neck-elongation contenders are competition over food or sex.

Today, these highly social mammals tower up to 5.8 meters (19 feet). A large proportion of that height stems from their incredibly long necks, which reach more than 1.8 meters high, despite only having the usual seven mammalian neck bones.

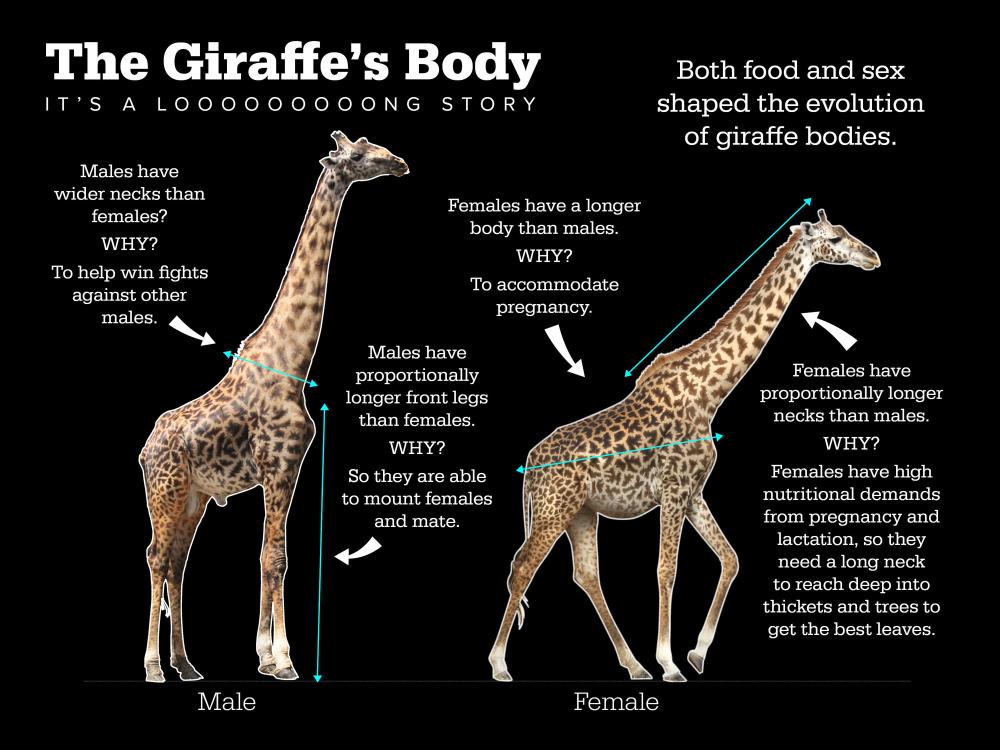

To evolve such outstretched necks, the entire posture of a giraffe had to adjust. Their necks, for instance, shifted a little more toward their back end, so they could maintain balance. Such an extreme specialization doesn't leave much wiggle room for body variations, yet these animals still display a significant size difference between males and females.

This discrepancy, as well as how males neck-slam in fierce battles for love, is what led some researchers to suspect that competition between males for mates drove the neck elongation of giraffes – just as sexual selection leads to a peacock's awkward and absurdly fancy tail.

But that may not be true after all.

"The necks-for-sex hypothesis predicted that males would have longer necks than females," explains Pennsylvania State University biologist Doug Cavener. "And technically they do have longer necks, but everything about males is longer; they are 30 percent to 40 percent bigger than females."

Using thousands of publicly accessible photos from repositories such as Flickr, the researchers tracked how different captive Masai giraffes (Giraffa tippelskirchi), kept at zoos across North America, grew over time.

Analyzing relative body proportions across wild animals and different species, too, Cavener and colleagues found that while male and female giraffes begin with similar proportions in their youth, males' proportions change when they reach sexual maturity. This means that adult females end up with proportionally longer necks than adult males, whereas adult males have proportionally wider necks than adult females.

As a result, the team believes natural selection pressure on the necks of female giraffes eventuated in their iconic length, whereas sexual selection pressures are responsible for the width of the male necks.

"Once females reach four or five years of age, they are almost always pregnant and lactating, so we think the increased nutritional demands of females drove the evolution of giraffes' long necks," argues Cavener.

"Rather than stretching out to eat leaves on the tallest branches, you often see giraffes – especially females – reaching deep into the trees. Giraffes are picky eaters – they eat the leaves of only a few tree species, and longer necks allow them to reach deeper into the trees to get the leaves no one else can."

Longer necks may help female giraffes prepare for pregnancy, but for males, length doesn't seem to be as important as width. The wider a male neck, the better it may be during fights against other males for mates, researchers suggest.

Sadly, numbers of these vulnerable, humming giants have declined by 40 percent since 1985.

"If female foraging is driving this iconic trait as we suspect, it really highlights the importance of conserving their dwindling habitat," says Cavener.

"Populations of Masai giraffes have declined rapidly in the last 30 years, in part due to habitat loss and poaching, and it is critical that we understand the key aspects of their ecology and genetics in order to devise the most efficacious conservation strategies to save these majestic animals."

This research was published in Mammalian Biology.