For several decades, scientists have wondered why giant star-shaped sand dunes found across many modern deserts don't appear in geological records.

To date, the count stands at one that grew more than 250 million years ago in what is now north-east Scotland. The fact no others have been found is something of a surprise given they can now be found across Africa, Arabia, China, and North America, and even on extraterrestrial deserts on Mars and Saturn's moon Titan.

A new study now offers up a possible explanation: that we just haven't known what to look for.

Researchers from University College London and Aberystwyth University in the UK have created the first detailed analysis of a star dune, choosing as their subject the Lala Lallia ("highest sacred point") dune in southeast Morocco. The hope is that this analysis will now better help star dunes to be spotted in sedimentary rock.

"This research is really the case of the missing sand dune," says Geoff Duller, a professor in Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University.

"It had been a mystery why we could not see them in the geological record."

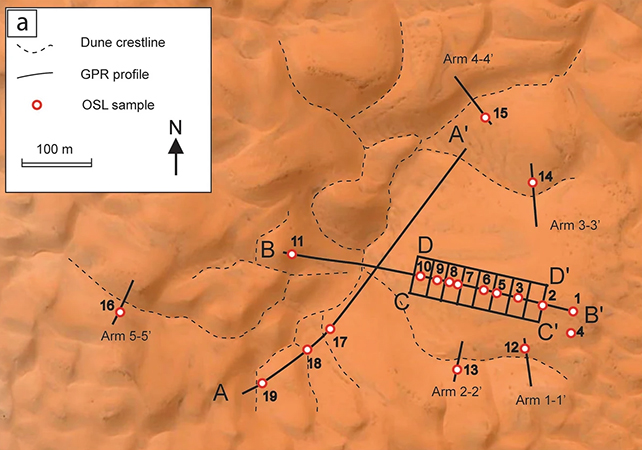

Lala Lallia is 100 meters (328 feet) high, with the radiating limbs that give the sand dune its name stretching out to a total arm-span of 700 meters. Using a mineral dating technique that pinpoints when sand grains deep inside the dune last saw sunlight, the team estimated the base of the dune to be around 13,000 years old.

The findings came as something of a surprise. In spite of the foundation's old age, much of the upper dune's formation had taken place only over the last thousand years. The structure also happens to be moving west across the desert at the rate of around 50 centimeters (almost 20 inches) per year.

That speed of formation and movement should help more star dunes to be identified in the geological record.

"Using ground penetrating radar to look inside this star dune has allowed us to show how these immense dunes form, and to develop a new model so geologists know better what to look for in the rock record to identify these amazing desert features," says sedimentologist Charlie Bristow, from University College London.

Star dunes are created by shifting wind patterns, with the largest known one on Earth standing some 300 meters (984 feet) high in the Badain Jaran Desert in China. Despite their ubiquity, to date there hasn't been a huge number of studies done on them.

The challenge now is to go back to the geological record with the new analysis, and try and identify star dunes that might otherwise have been missed, because researchers weren't sure of the size or the patterns that they were looking for.

"It's only because of new technology that we can now start to uncover their secrets," says Duller. "These fantastic star dunes are one of the natural wonders of the world."

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.