Scientists have discovered great potential in an up-and-coming drug that targets an aggressive form of brain cancer.

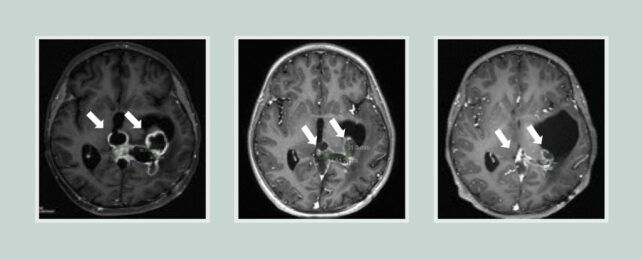

Called diffuse midline gliomas (DMGs), these deep-rooted brain tumors often develop in childhood, and there are currently no effective treatments available to tackle them.

Part of the challenge has been finding drugs that can cross from the blood into the brain in sufficient concentrations.

One drug, called ONC201, has shown promise for other kinds of tumors in the nervous system. Following research suggesting it could be effective against a DMG with a specific mutation, an international team of researchers has carried out a trial putting the dopamine receptor blocker to the test.

Two clinical studies were carried out on groups of volunteers – one consisting of 30 children and adolescents with DMG, the other of 40 individuals that included adults.

The median overall survival time with ONC201 treatment was 22 months for tumors that didn't recur, with almost a third of patients living for over two years. That compares with a median overall survival time of 11-15 months without treatment.

"Prior to this study, there have been more than 250 clinical trials that have not been able to improve outcomes," says pediatric neuro-oncologist Carl Koschmann from the University of Michigan in the US. "These results are potentially a major crack in the armor."

Researchers had previously looked at ONC201 as a cancer drug because of the way it targets neural pathways for the chemical messenger dopamine – pathways that are often more abundant in tumors.

Previously, ONC201 had shown promise when treating DMGs with the H3K27M mutation. Earlier studies also showed that the compound could pass through the blood-brain barrier, a built-in biological safety net for our brains that makes delivering drugs to brain tumors particularly difficult.

That prompted this latest study, a phase 1 clinical trial. The team collected cerebrospinal fluid from patients to try and get a better idea of what ONC201 was doing – and it was discovered that it affected the mitochondria (or power plants) of the cancer cells, increasing levels of a metabolite called L-2HG.

As a result, the epigenetic signals (like on/off switches for specific genes) associated with the tumor that help drive its rapid spread were reversed back closer to what they would be in normal cells. The longer the treatment went on for, the greater this reversal was.

"This could explain why this patient population was responding so well to the drug, because it had this specific epigenetic abnormality that could be turned off by ONC201," says neuropathologist Sriram Venneti from the University of Michigan.

While we're still a long way from a cure for DMG cancer, the signs are good that we now have a compound that can get past this tumor's defenses. More clinical trials are already underway, testing how ONC201 might work in combination with other treatments.

Right now, radiation therapy is the go-to treatment for this kind of cancer – but in an area as delicate as the brain, there can be a lot of collateral damage, which is why scientists are searching for a more precise, targeted option.

"It's an incredibly difficult tumor to treat," says Koschmann.

The research has been published in Cancer Discovery.