The world now has a rocket thruster that uses air instead of fuel - and it could change how satellites fly in the lowest orbits around Earth.

The new thruster can collect, compress, electrically charge and then release air molecules, removing the need for chemical fuel. All that's needed is some electricity, which can usually be harvested from the Sun.

According to the lab tests run on the ground by the team from the European Space Agency (ESA) behind the project, the new thruster could power "a new class of satellites", operating for years around planets such as Earth or Mars.

How satellites might work with the new thruster. (ESA)

How satellites might work with the new thruster. (ESA)

"This result means air-breathing electric propulsion is no longer simply a theory but a tangible, working concept, ready to be developed, to serve one day as the basis of a new class of missions," says one of the ESA scientists, Louis Walpot.

The ESA has been busy working on this for more than a decade. Its GOCE gravity mapper satellite ran for more than five years using a similar type of thruster, though it also relied on 40 kilograms (88 pounds) of xenon as a propellant to keep it going.

Now the agency has worked out how to use air instead – and while there are no air molecules out in the vacuum of space, enough can be collected at low orbits to give a satellite a periodic boost.

These outer reaches of the atmosphere gradually slow down orbiting satellites and pull them back to Earth, which is why such boosts are required.

Key to working this out was finding a way to collect and compress the scarce air molecules rather than have them simply bounce away. The electrical charge and ionisation is crucial here, providing the acceleration needed.

"The team ran computer simulations on particle behaviour to model all the different intake options," says Walpot. "But it all came down to this practical test to know if the combined intake and thruster would work together or not."

"Instead of simply measuring the resulting density at the collector to check the intake design, we decided to attach an electric thruster. In this way, we proved that we could indeed collect and compress the air molecules to a level where thruster ignition could take place, and measure the actual thrust."

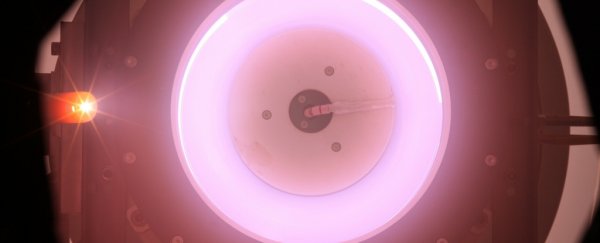

The thruster uses a special two-phase process. (ESA)

The thruster uses a special two-phase process. (ESA)

The team set up a test vacuum chamber and thruster in Italy, simulating the environment at an altitude of 200 kilometres (124 miles) and at a satellite speed of 7.8 kilometres-per-second (4.8 miles-per-second).

With no valves or complex parts, all that's needed is the power to electrically charge the molecules to accelerate and eject them. A special two-stage system was designed for more efficient charging.

The rocket thruster was tested with xenon, then a nitrogen-oxygen mixture, and then finally solely with atmospheric air molecules.

There's still a lot more work to do before such a system can be fitted to a satellite, but this is solid evidence that such a system is possible.

The main problem with chemical propellant is that it needs to be loaded on board rockets on Earth, weighing down spacecraft and adding to the cost of space travel. The further we want to go, the more those problems are compounded.

That's why researchers are hard at work exploring alternative ways to zip round the Universe, and now we've got a highly efficient system ready for satellites that works by air and electricity alone. That's pretty amazing.