Swimming through petroleum-infested waters is not exactly good for a dolphin's health, and if that dolphin is pregnant, the ramifications are even more dire.

Following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2011, successful pregnancies in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) plummeted, mainly from reproductive failures such as foetal mortality, distress and pneumonia, all of which are closely tied to pollution.

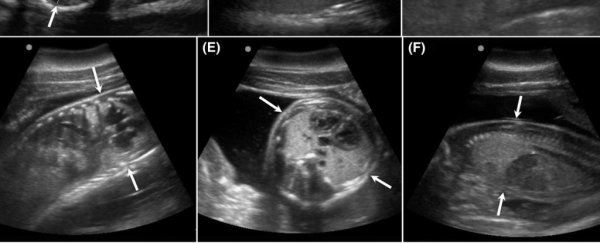

Understanding exactly why these pregnancies failed will be crucial for future dolphin and porpoise conservation. But while there are standard methods for calculating foetal growth and wellbeing in humans and other mammals (for example, horses), dolphin ultrasounds have historically lacked such clear and sophisticated assessments.

Now, an upgraded approach could allow us to detect foetal abnormalities and complications at all stages of dolphin gestation.

The images are an incredible scientific advance, but the reasons we need to take them are devastating.

(NMMF)

(NMMF)

"This advanced ultrasound technique is allowing us to diagnose problems as early as the first trimester of pregnancy in dolphins," says Forrest Gomez, director of medicine at National Marine Mammal Foundation (NMMF).

"That gives us a chance to determine if there is something that could be done to save the pregnancy, which could prove critical for populations of dolphins and porpoises that are at risk."

For humans and other animals, ultrasounds have proved time and again to be life-saving, and dolphins are no exception. For years, this technique has been used to evaluate a dolphin's reproductive success as well as its pulmonary, cardiac, hepatic, urinary, gastrointestinal and lymphatic systems.

Expanding on this earlier work, researchers at NMMF have now developed a consistent protocol for ultrasound monitoring in pregnant bottlenose dolphins.

From 2010 to 2017, the team carefully monitored 16 healthy pregnancies in a dozen bottlenose dolphins managed by humans.

While that is a relatively small sample size, over 200 ultrasound examinations were made in the study, and up to 70 factors were measured in each scan, allowing the team to determine typical readings for both the dolphin foetus and placenta.

By establishing these parameters, the upgraded approach could allow veterinarians to promptly diagnose congenital anomalies and pregnancy issues early on.

"We can now re-create the human 20-week foetal ultrasound exam in dolphins, which means we can better understand the health challenges dolphin mothers and their babies are facing," says Cynthia Smith, executive director of NMMF.

"This is a game-changer for the conservation of bottlenose dolphins and other small cetaceans around the world."

(Peter Asprey/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 3.0)

(Peter Asprey/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 3.0)

After the Deepwater disaster, female dolphins living within the spill's footprint gave birth to living calves only 19 percent of the time compared to the usual 65 percent seen in unaffected areas.

Tragically, after the spill, many mother dolphins were seen carrying around the carcasses of their stillborn calves, and while this hasn't been connected directly to oil pollution, the timing is certainly suspicious.

In the first years after the spill, for instance, dolphins in Barataria Bay showed reproductive failure rates four times greater than those in non-oiled areas, and strandings of dolphin calves were excessively high in this region as well.

With an advanced ultrasound technique, veterinarians can now monitor at-risk pregnancies in dolphins with greater accuracy than ever before, measuring foetal heart beats, aortic volumes and blubber thickness, all of which can help pinpoint a fetus' growth and well-being.

During a dolphin ultrasound, for example, the authors found that lack of foetal movement was not necessarily ominous, but if it was seen in conjunction with a lack of cardiac motion or abnormalities in organ appearance, then it was likely to represent foetal loss.

Additional studies will be needed to confirm these findings and expand diagnostic methods, but the authors hope such information can help us to figure out when, where and why dolphins are struggling with reproduction.

The study was published in Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound.