Computer simulations suggest that evolution itself could be evolving, depending on environmental pressures. This would mean that not only do living things change over generational time but the processes that change them are changing too.

This is a hard thing to study, given the large timescales that can be involved in the evolution of living things. So University of Michigan evolutionary biologist Bhaskar Kumawat and colleagues turned to randomly mutating, self-replicating programs that compete in a digital environment, where they face rewards and challenges.

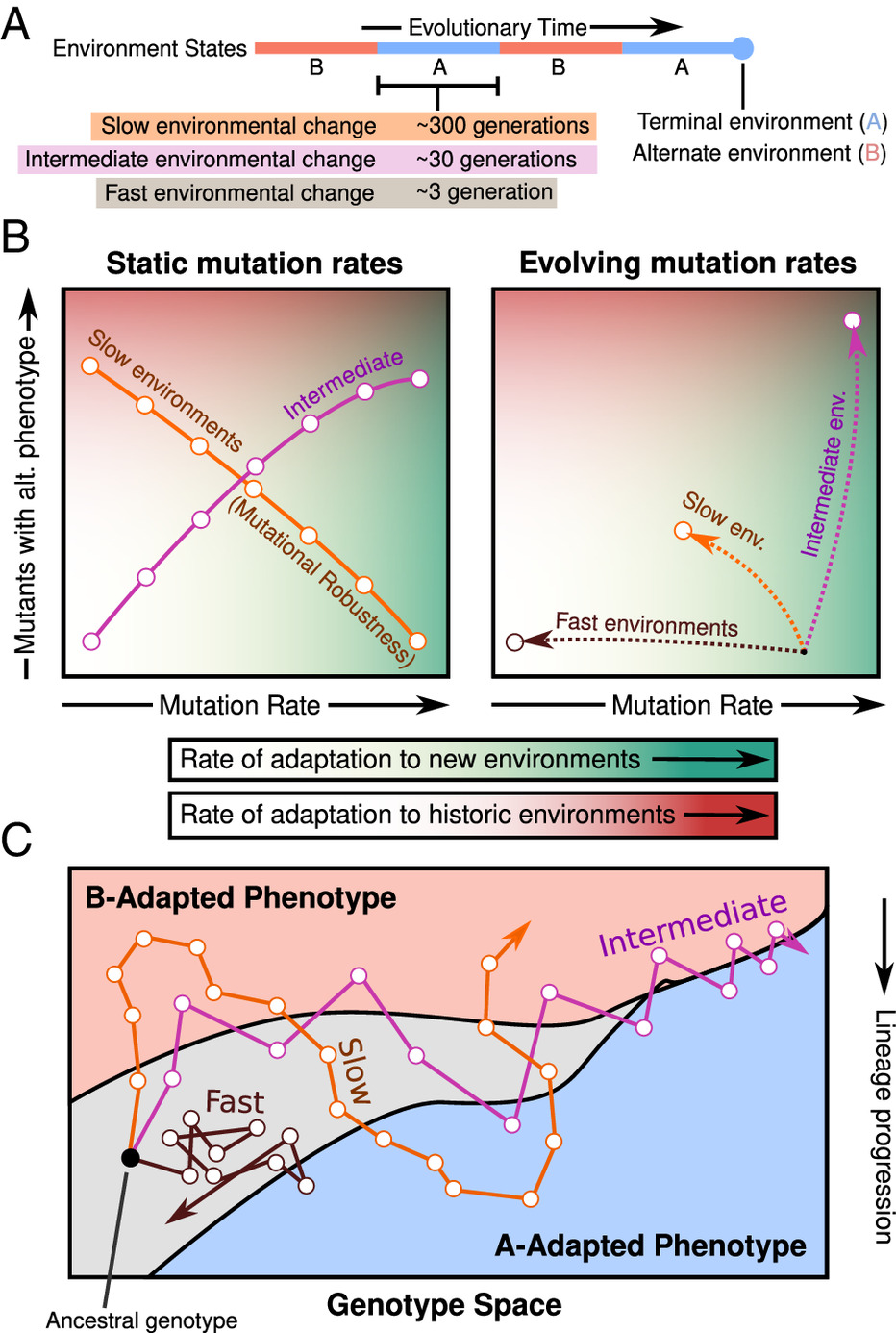

In a series of simulations, populations had access to two components – one rewarding and one toxic. However, in some scenarios these components would switch traits at fast, intermediate or slow rates, requiring populations to adapt to new environments.

These tests revealed two mechanisms of 'evolvability,' by which the process of evolution can change over time. One is a shift in the population's mutation rate.

"Higher mutation rates need not lead to improved evolvability in any one specific environment but have a broad adaptive impact when exposed to many environmental challenges," the team explains in their paper.

Typically, in a stable environment mutation rate is minimized as random mutations come with a risk of negative consequences. Mutation rates also plummet when an environment changes too rapidly.

By challenging the virtual 'organisms' with periods of change interspersed with generational lulls of normalcy, the balance between the risk of negative mutations and the need to adapt to newness gradually shifts.

This led to an increased rate of mutation, allowing rapid adaptation to new environments.

"Remarkably… we see that the populations maintain much higher mutation rates in environments changing at intermediate rates," Kumawat and colleagues found.

A second mechanism seems to fine-tune the landscape of these mutations, in a way that allows life to shift back and forth between previously known environments over generations, for example between arid and humid conditions.

The virtual populations that continually seesawed between new and familiar environments ended up having a thousandfold increase in mutations, ultimately finding combinations that allow them to more easily switch between opposing traits required.

"The mutational neighborhood that populations end up occupying – finding through evolution – are places where single mutations are able to reconfigure this pathway," explains University of Michigan evolutionary biologist Luis Zaman.

But this increase in evolvability only occurred when the environmental shifts had long enough periods between each switch – ideally 30 generations.

Incredibly, once increases in evolvability occurred, they seemed to stick, even after further mutation. This may be a way life can stack on even more complexity over evolutionary time.

The computer simulation best mimics single-celled, asexual organisms, the researchers qualify, but they believe these principles are still likely to play a role over longer terms for more complex organisms.

While the concept of evolving evolution is still contentious, there are some new examples arising from studies in bacteria.

"Life is really, really good at solving problems," says Zaman. "Why is evolution so seemingly creative? It seems like maybe that ability is something that evolved itself."

This research was published in PNAS.