The birth and development of civilisation on the Polynesian islands continues to be a source of fascination for historians, and new evidence shows that Native American visitors may well have been established in the area hundreds of years before European settlers.

After a detailed DNA analysis of the genomes of more than 800 Polynesians and Native Americans, both modern and prehistoric, researchers have found evidence of contact between the two groups as far back as 1200 CE.

The team found signs of genetic admixture that they traced to a single contact event around that time, and it could mean a rethink as to how populations grew and evolved on the islands before European traders and missionaries arrived at the start of the 18th century.

"Our analyses suggest strongly that a single contact event occurred in eastern Polynesia, before the settlement of Rapa Nui, between Polynesian individuals and a Native American group most closely related to the indigenous inhabitants of present-day Colombia," the researchers explain in their paper.

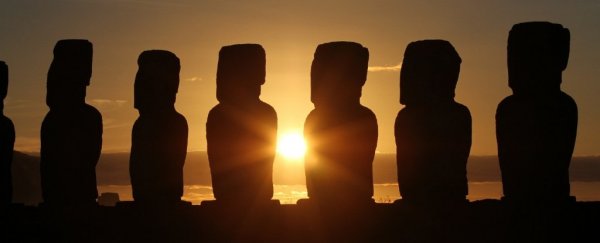

Interestingly, this is the first genetic study to indicate that the initial point of contact for American travellers was not Easter Island (Rapa Nui) – the closest island to South America – but rather one of the eastern Polynesian archipelagos, such as the South Marquesas.

The same idea was previously put forward by Norwegian explorer and anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl, who famously made the 8,000-kilometre (5,000-mile) journey from Peru to the Tuamotu Islands, in a traditional wooden Inca raft called the Kon-Tiki, to show it could feasibly be done.

Heyerdahl's voyage was inspired by islander legends, which held that their ancestors came from the east.

While past studies have focussed on Easter Island as the most likely landing point for South American seafarers, due to it being the shortest distance away, the team behind the new findings says that the real story could be somewhat different.

The researchers continued to dig into the intriguing history of Easter Island too, suggesting from their analysis that Native Americans arrived separately to Europeans – something that earlier studies have been unable to agree on.

The new study doesn't stand alone. There are certain similarities between the statues of prehistoric Colombia and the eastern Polyesian islands, links in the language (including 'kumala', the word for sweet potato), and research into favourable ocean currents of the time that back up this latest research.

The study authors admit that there are other possibilities – that Polynesians sailed to South America and returned with Native Americans, for example – but say that their hypothesis about initial contact around 1200 CE is the most likely explanation.

Almost every new study on the history of this part of the world is a fascinating insight into the way scientists are able to combine techniques from multiple disciplines to try and make educated guesses about what happened many centuries ago, and that's something that's also acknowledged in the new paper.

"Our results show the usefulness of genetic studies of modern populations, which allow for large sample sizes to unravel complex prehistoric questions, and demonstrate the importance of combining anthropological, mathematical, and biological approaches to answer these questions," the team writes.

The research has been published in Nature.