Whatever you're doing for your New Year's celebrations, it's not going to be as awesome as New Horizons. On New Year's Day, the space probe will zoom right up close past an object in the Kuiper Belt called 2014 MU69 - nicknamed Ultima Thule.

This will make Ultima Thule the farthest Solar System object to be visited by a spacecraft (the Voyager probes' last encounters were with Saturn for Voyager 1 and Neptune for Voyager 2).

New Horizons has mostly been napping after it left Pluto behind nearly three-and-a-half years ago, in July 2015. It's travelled a distance of nearly a billion miles (1.6 billion kilometres) since then, and it's pretty much right on schedule.

However, pinning down an exact date for the flyby wasn't possible until recently, because NASA scientists had no idea what hazards exist in the space around the object.

New Horizons sent back its first images of Ultima Thule in August, and since then, a team has been working to map those hazards so they could plot the best course to avoid them - at breakneck speeds of 50,700 kilometres per hour (31,500 miles per hour), even a tiny impact could destroy the spacecraft.

And they can't just take first-person control of New Horizons, swerving obstacles like you'd do in a sci-fi space plane. They need to know ahead of time what they're dealing with, because communication with the probe is incredibly slow.

At time of writing, New Horizons is 44.10 astronomical units from Earth - or around 6.11 light-hours. That means that, even though radio waves travel at light speed, they still take over 6 hours to reach the probe.

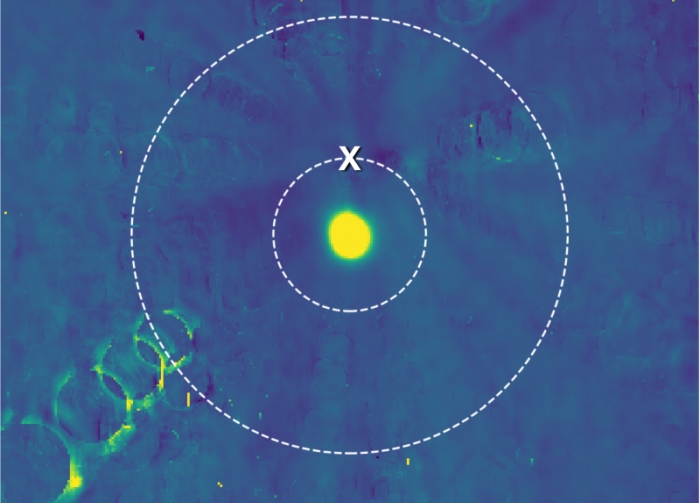

Composite of hundreds of images shot by LORRI. (NASA/Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

Composite of hundreds of images shot by LORRI. (NASA/Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

But, of course, the New Horizons team has now seen what's in the space around Ultima Thule using the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), and there are no hazards such as moons or rings that will hinder the trip.

New Horizons is going to be travelling along a pretty direct line, and will reconnoitre with Ultima Thule at a distance of just 3,500 kilometres (2,200 miles).

If it had had to detour, its flyby would have been a much greater distance, and would show Ultima Thule in less detail. The image above shows the two flyby distances. The yellow dot in the middle is Ultima Thule, and X marks the ideal flyby distance. The larger circle is the flyby distance that would have been used if hazards had been detected.

"Our team feels like we have been riding along with the spacecraft, as if we were mariners perched on the crow's nest of a ship, looking out for dangers ahead," said hazards team lead Mark Showalter of the SETI Institute.

"The team was in complete consensus that the spacecraft should remain on the closer trajectory, and mission leadership adopted our recommendation."

So what is Ultima Thule (pronounced thoo-lee)? Although its name is strangely reminiscent of Conan the Barbarian villain Thulsa Doom, the meaning is actually much nerdier.

Thule was a mythical island that appeared in the far North on medieval maps; the name means "beyond Thule", or beyond the borders of our known sphere.

What we know about it is that it's an irregular chunk of rock in the Kuiper belt of asteroids. It's either two asteroids joined together, or a very close binary, with one measuring around 20 kilometres across, and the other 18 kilometres across (12 and 11 miles). It has a reddish hue, and takes over 296 years to complete one full orbit of the Sun.

New Horizons' closest approach will be just after midnight, at 00:33 EST, and it's expected that it will answer some of the burning questions we have about Ultima Thule. What exactly is it? What does it look like? What makes it red? What is its surface composition? And does it have methane or ice?

Once these questions are answered, the team will choose a formal permanent name to submit to the IAU. But for now, everyone is getting amped up for the history-making flyby.

"The spacecraft is now targeted for the optimal flyby, over three times closer than we flew to Pluto," said New Horizons' principal investigator Alan Stern. "Ultima, here we come!"