Researchers have witnessed two viruses – influenza A and respiratory syncytial virus – fuse together to form a single, hybrid virus.

While competition between viruses has been researched in some detail, this new finding provides researchers with an unusual example of one virus coopting another for its own benefits.

"This kind of hybrid virus has never been described before," virologist and senior author Pablo Murcia told The Guardian. "We are talking about viruses from two completely different families combining together with the genomes and the external proteins of both viruses. It is a new type of virus pathogen."

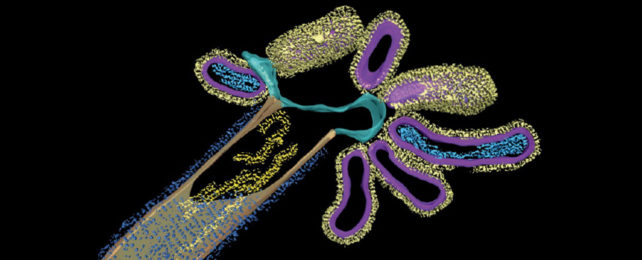

The hybrid virus looks like a gecko's foot under the microscope, with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) forming the legs and influenza A virus forming the toes.

It was discovered during a lab-based experiment designed to analyze interactions between viruses during infection to better understand clinical outcomes, pathogen behavior, and transmission.

Human lung cells were exposed to both viruses, as well as each virus individually as a control group. An assortment of microscopy techniques then revealed filamentous structures consistent with a hybrid of both virus particles.

When these two viruses join forces, influenza A appears to infect a higher number and broader range of human cells. The influenza A particles were found to evade the immune system by displaying the RSV surface proteins, giving the virus a survival advantage.

The hybrid also spread into cells that lacked influenza receptors, which could allow influenza A to move further down the respiratory tract into the lungs and lead to more severe infections.

Sadly for RSV, this merger isn't such a great deal, with influenza A's presence significantly rducing its capacity for replication.

The experiment was limited to a lab setting, which "cannot fully capture the spatial and physiological complexity of the whole respiratory tract," the researchers say.

However, the improved fitness of influenza when merged into a hybrid virus suggests that such blatant theft of another virus's toolkit may play a role in viral pneumonia.

"RSV tends to go lower down into the lung than the seasonal flu virus, and you're more likely to get more severe disease the further down the infection goes," says Dr Stephen Griffin, a virologist at the University of Leeds who was not involved in the study.

"It is another reason to avoid getting infected with multiple viruses, because this [hybridisation] is likely to happen all the more if we don't take precautions to protect our health," he says.

Influenza A alone causes over 5 million hospitalisations each year, while RSV is the most common cause of acute lower respiratory tract infections in infants, with reinfection common in later life.

The study "raises questions about fundamental rules that govern viral assembly," and there could be other hybrid viruses out there yet to be discovered, the researchers write.

"Respiratory viruses exist as part of a community of many viruses that all target the same region of the body, like an ecological niche," says virologist and lead author Joanne Haney.

"We need to understand how these infections occur within the context of one another to gain a fuller picture of the biology of each individual virus."

This paper was published in Nature Microbiology.