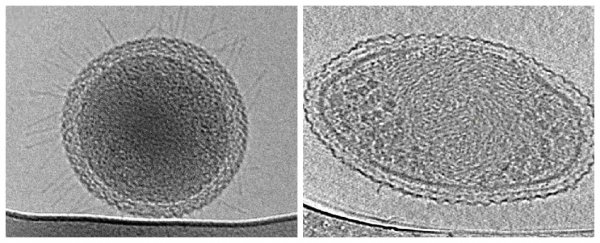

For the first time, scientists have captured images of ultra-small bacteria, putting to rest a decades-old debate over whether or not these minuscule creatures actually exist.

Led by scientists from the US Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California, Berkeley, the team has confirmed that these single-celled organisms have an average volume of 0.009 cubic microns. One micron is one millionth of a metre, which means 150 of them could fit inside an E. coli cell. This is the smallest life-form known to science, and they could be as small as life gets on Earth.

In 1996, researchers published a description of a meteorite that fell from Mars, which sparked a long and complicated debate over the existence of what they called 'nanobacteria', later also described as nanobes. Various teams argued over whether life, theoretically, could live to be that size, but the debate didn't really get anywhere because no one really had any evidence for either side. One side said all the things needed for life - DNA, RNA, proteins and solvents - couldn't actually fit inside a cell that small, while others said life could be that small, but just in a starved, inactive state.

Researchers argued over the theoretical limit for how small a cell could get in diameter and volume, and one team even reported finding some marine nanobes, but lacked direct electron microscopic evidence to prove they fit inside the size range to classify them as such. But now, bacteria found in some Colorado groundwater have been imaged, and these things are undeniably tiny - several times tinier than several estimates for the lower size limit of life on Earth, in fact. And as difficult as it is to see them, the researchers think they could actually be quite common.

Of course, that doesn't mean they're not super-weird. Publishing their description of these creatures in Nature Communications, the team says the bacteria cells are full to the brim with tightly packed spiral structures they think is probably DNA, and they contain a small amount of RNA. They function according to a very basic metabolism, which suggests that they're probably parasitic, being unable to meet their own basic needs without the assistance of more sophisticated life-forms. Hair-like appendages called pili could actually help them to attach to other microbes, the team suggests.

The various types of ultra-small bacteria found belong to one of three microbial phyla, all of which scientists have struggled to study in the past.

"These newly described ultra-small bacteria are an example of a subset of the microbial life on earth that we know almost nothing about," one of the team, Jill Banfield, a Senior Faculty Scientist in Berkeley Lab's Earth Sciences Division, said in a press release. "They're enigmatic. These bacteria are detected in many environments and they probably play important roles in microbial communities and ecosystems. But we don't yet fully understand what these ultra-small bacteria do."

"There isn't a consensus over how small a free-living organism can be, and what the space optimisation strategies may be for a cell at the lower size limit for life. Our research is a significant step in characterising the size, shape, and internal structure of ultra-small cells," one of the team, Birgit Luef, now at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, added.

The team was able to capture the ultra-small bacteria - they don't have a more official name than that yet - by filtering groundwater through successively smaller filters, getting right down to an incredible 0.2 microns. This is so small, it's how we sterilise water, which means we're assuming no life could get through those holes. Except that in this case, the 'sterilised' water was positively teeming with organisms.

The bacteria were flash frozen and taken back to the lab at Berkeley, where their internal structures were captured using using 2-D and 3-D cryogenic transmission electron microscopy. Using this technology, the researchers were able to see cells in the process of dividing, which means that not only were these creatures not starved or inactive, as had been previously suggested, but they were healthy, active, and replicating themselves.

The task now is to figure out, well, basically everything about these minuscule creatures. "We don't know the function of half the genes we found in the organisms from these three phyla," Banfield says.

Can't wait to get you know you better, ultra-small bacteria!